Welcome to a/symmetric, our weekly newsletter. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric. To receive issues over email, subscribe here.

This week:

- China eyes a supercomputing internet. Can it leverage networks to leapfrog the US and sidestep restrictions?

- Weekly Links: How money laundering fuels the fentanyl crisis, OpenAI’s China choice, and the trade-offs between high tech and old school weapons.

Dawn of the supercomputing internet

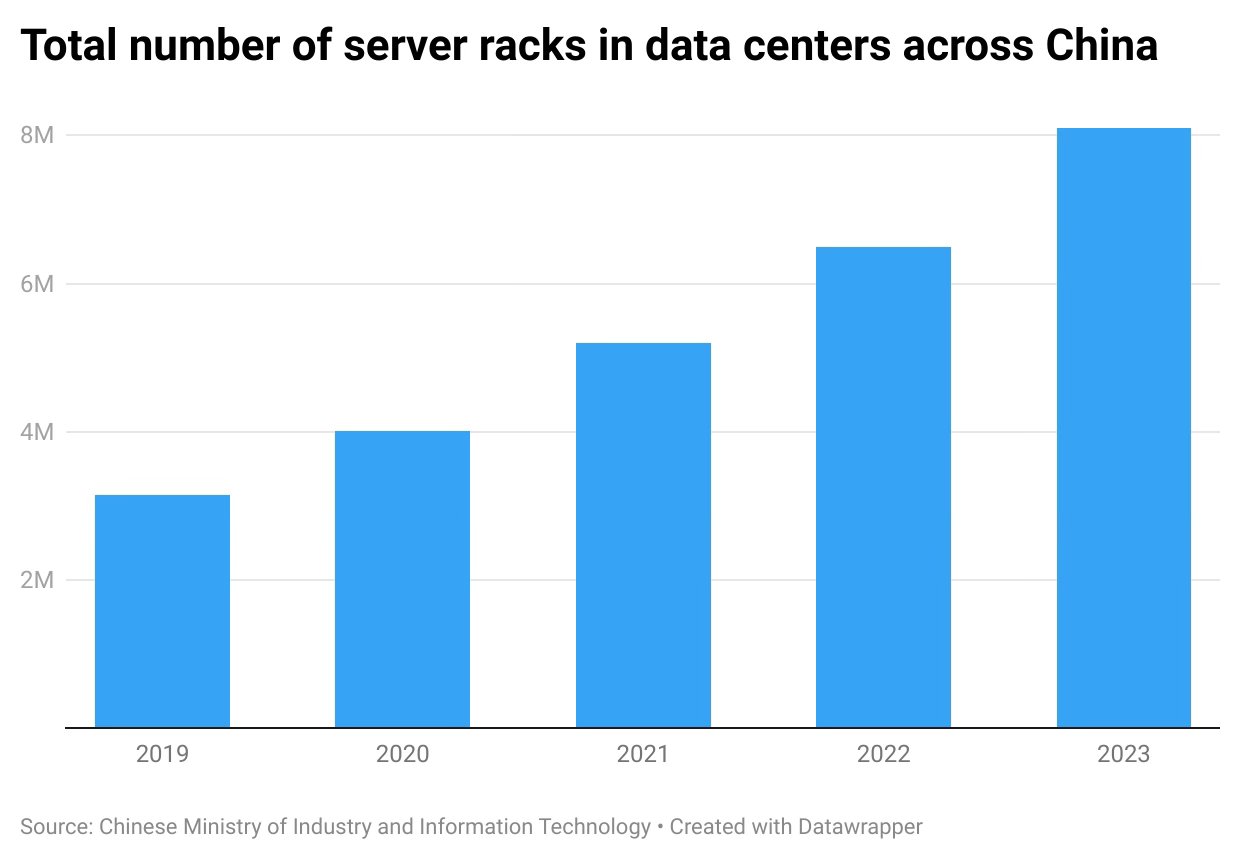

As we reported in March, China is building lots of data centers and ramping up total available computing power nationwide.

Latest available government figures show that the country had 8.1 million standard server racks as of end-2023, up 25% over the previous year and continuing numerous years of fast growth.

But China’s computing ambitions don’t stop at data centers. Beijing hopes to create a “supercomputing internet” (超算互联网) that can popularize, standardize, and make more efficient access to and use of computing power for widespread commercial and industrial applications — and in doing so catch up to the global leader in computing, the United States.

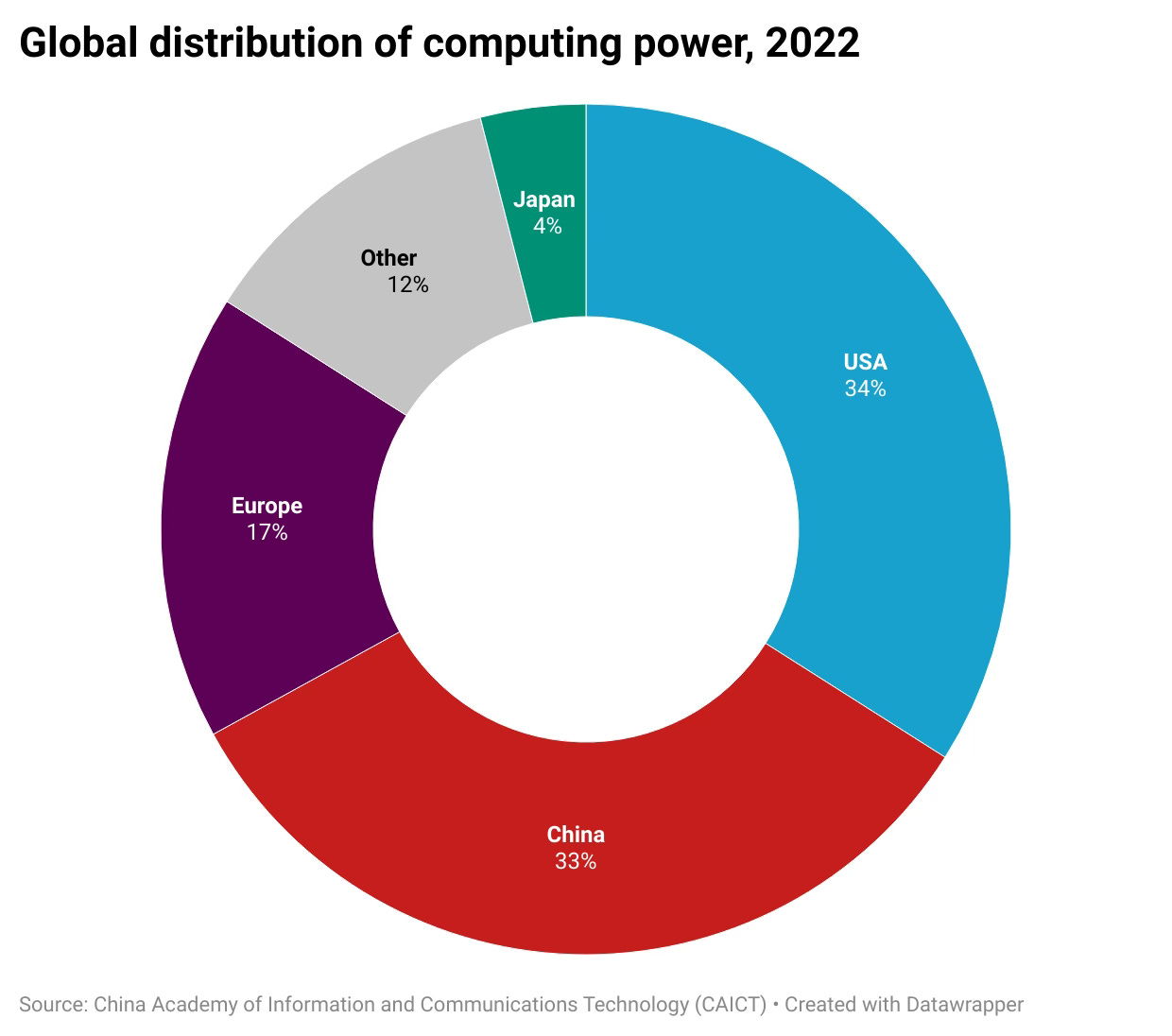

“China’s total computing power ranks second in the world, behind only the US. But the gap is reflected in the fact that the US has world leading chip capabilities, hardware level, and financial capital preference,” the state-owned CITIC investment group wrote last year.

The US also benefits from a high concentration of computing power among several tech giants, according to CITIC. By contrast, computing power in China is more fragmented, posing challenges for integrating different operating systems and modes to support AI development.

How then might China try to close its computing gap with the US? By taking a differentiated, asymmetric approach.

“China cannot build a highly concentrated computing power capacity in the way and path of the US,” CITIC argued. “We can only find a Chinese solution suitable for China’s development stage to strengthen computing via a network, and achieve computing-network integration (以网强算、算网融合).”

The supercomputing internet fits just that bill.

Computing history 101

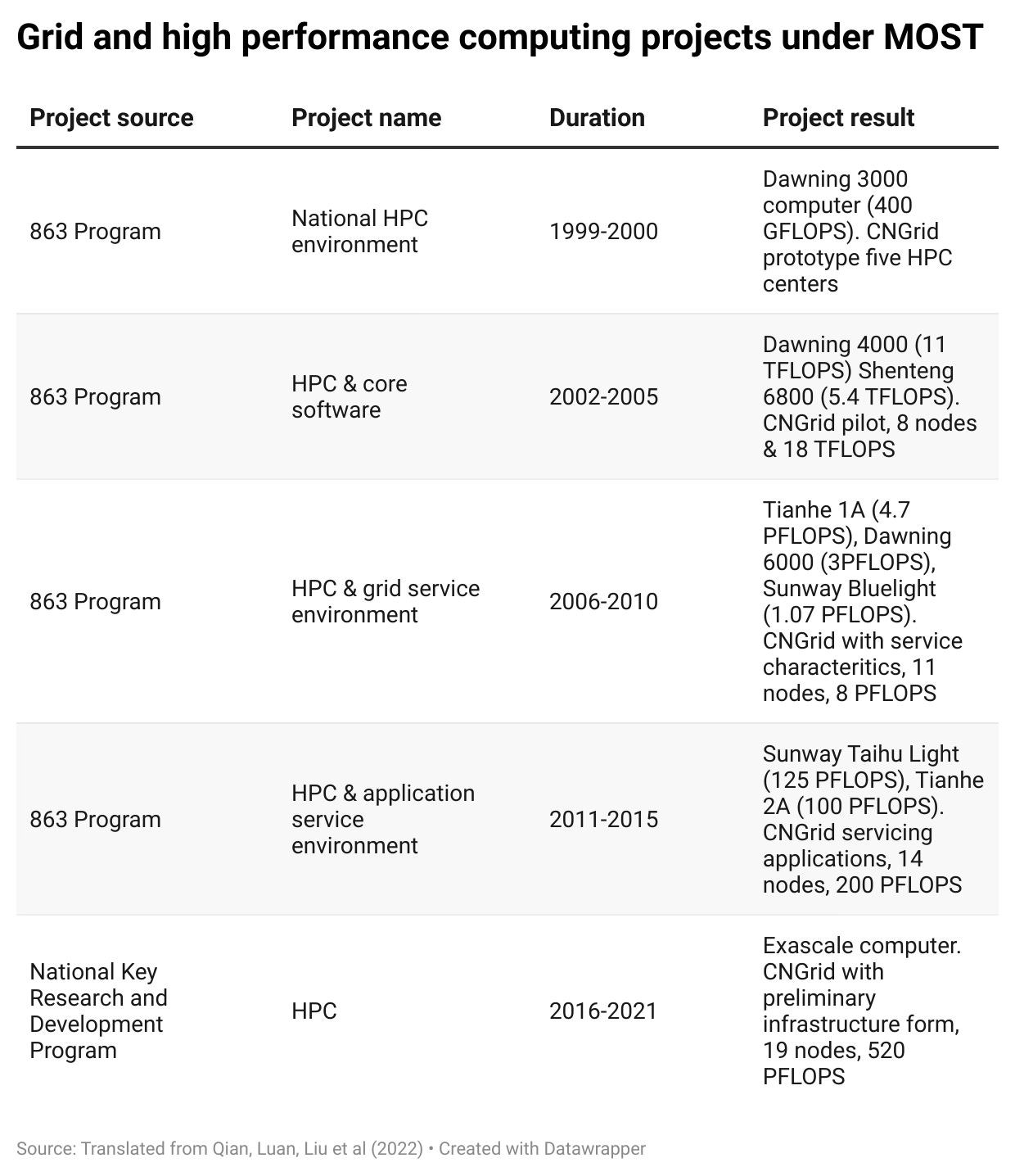

China’s aspirations for a supercomputing internet trace back to the turn of the millennium, when the country first began researching a national high performance computing network for R&D purposes.

Dubbed CNGrid, the effort was overseen by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and funded by a state science research program. The “grid” part of CNGrid is a nod to the concept of grid computing (itself a reference to the power grid), which had begun to gain traction among US researchers in the 1990s. Over the next two decades, Beijing provided targeted funding to further develop CNGrid, adding more connection points and increasing computing power.

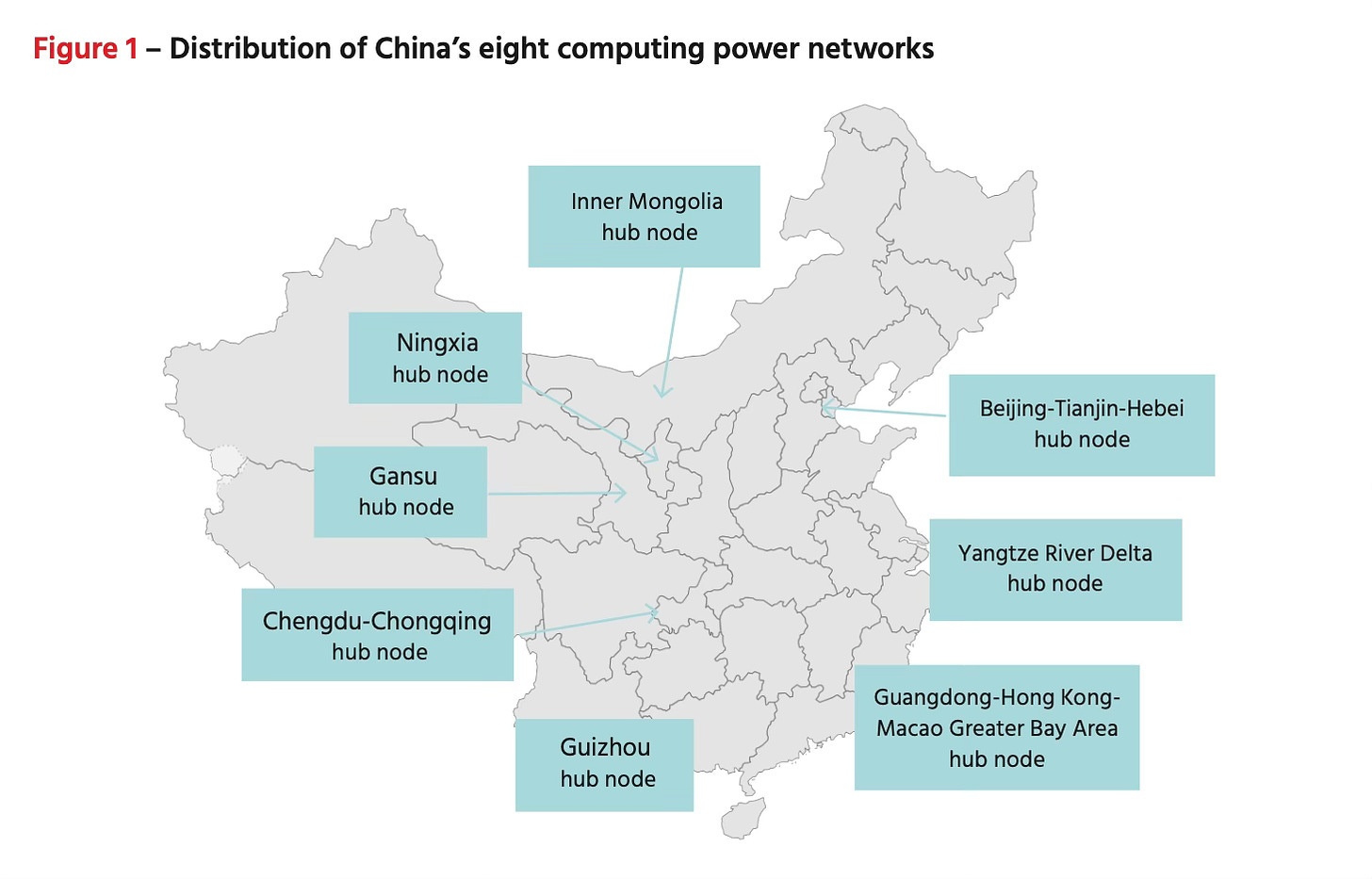

In 2022, Beijing launched the “Eastern data, Western computing” national strategy. The aim is to build an interconnected national computing network organized around eight major hub nodes. The five hubs in western provinces, where energy is cheaper and more abundant, focus on more resource-intensive and less time-sensitive computing work like processing, analysis, and storage. Meanwhile, eastern provinces have more developed digital economies, with greater demand for and creation of data.

Source: Hinrich Foundation

The supercomputing internet marks the latest stage in the evolution of China’s computing capacities. If early iterations of CNGrid connected high-performance computers, the advent of cloud computing and “Eastern data, Western computing” opened up the era of supercomputing-as-a-service. The supercomputing internet takes it all a step further.

“The supercomputing internet is new, and there is no precise definition yet,” Qian Depei of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said last year. “…[It] is not simply a network, but uses the concept and thinking of the internet to build and operate a national supercomputing infrastructure.”

From follower to pioneer?

In an indication of the project’s strategic importance, MOST last April established the Supercomputing Internet Consortium.

The consortium’s members are a who’s who of Chinese computing. They include eight national supercomputing centersthat are already hooked up to CNGrid; a national laboratory dedicated to intelligent computing; as well as Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiaotong University, both of which are CNGrid nodes. Leading the consortium is Qian, a prominent computer scientist who has been at the center of China’s computing development over the decades, including building CNGrid.

In April, China’s supercomputing internet officially launched, though details about its exact scope are scant. A lengthy report by the consortium published that same month provides some clues. It notes:

“The supercomputing Internet is a supercomputing infrastructure with Internet concepts and characteristics, an Internet-based high-performance computing service environment, and a deep integration of Internet innovation achievements and computing infrastructure operations. The supercomputing Internet should not only form an efficient data transmission network between various computing centers, but also build and improve a nationwide computing scheduling network and an application-oriented ecological collaboration network.”

…the core concept of the supercomputing internet is to connect multiple entities through an e-commerce platform to manage and dispatch multi-source, heterogeneous, and massive resources…the goal of supercomputing internet is not only to provide cloud-based computing resources, but also to build an upper-level application market to solve user business application problems.”

The focus here on applications is notable, particularly given China’s strong track record of application-driven innovation that has allowed it to leapfrog incumbents in numerous strategic technologies.

Indeed, the consortium views supercomputing applications as key to attaining global leadership in the domain, as well as to blunt US technology restrictions. It writes (emphasis added):

“Under the conditions of a strict external blockade, combining software and hardware, system optimization, and prioritizing applications are requisite ways to break the predicament. To judge heroes by the effectiveness of application, and shift from world-leading machine performance to world-leading application results should become the new goal pursued by China’s high-performance computing development.”

There’s also the perception, at least in China’s eyes, that the supercomputing internet is unprecedented. That would by definition make China a pioneer if it brings the concept to fruition, reversing its decades-long latecomer status in computing.

Weekly Links

️ Old school vs. high tech. The war in Ukraine makes clear “the continuing importance of old-school unguided artillery shells, the manufacturing of which is only now beginning to pick up in the US and Europe after decades of decline,” Finland’s permanent secretary of the defense ministry said in an interview. “They are immune to any type of jamming, and they will go to target regardless of what type of electronic warfare capability there may be,” he said. (WSJ)

️ “Why does OpenAI ban China,” asks Yiwen Lu, “while Microsoft takes advantage of its partner’s exit to attract more Chinese customers? It has a lot to do with the different incentives of both businesses… In some ways, this is probably the puzzle for all big enterprises: despite all the heartache, it still doesn’t make sense to give up on China.” (ChinaTalk)

️ Central policy, money laundering, and the fentanyl crisis. Zongyuan Zoe Liu writes in her detailed monthslong investigation: “China occupies key positions both upstream and downstream of the fentanyl crisis playing out on America’s streets. Chinese companies are the largest suppliers of chemical precursors used to make fentanyl. China also serves as the base of operations for criminal money laundering organizations that facilitate the sale of fentanyl.” (Foreign Policy)

(Photo by Thomas Jensen on Unsplash)