Welcome to a/symmetric, our weekly newsletter. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric. To receive issues over email, subscribe here.

This week:

-

China launched the first satellites of its megaconstellation. The effort is aimed at a grand prize: 6G leadership

- Weekly Links: Baijiu and chips, smoothing energy demand, and industrial policies for small businesses

The 6G ambitions behind China’s Starlink bets

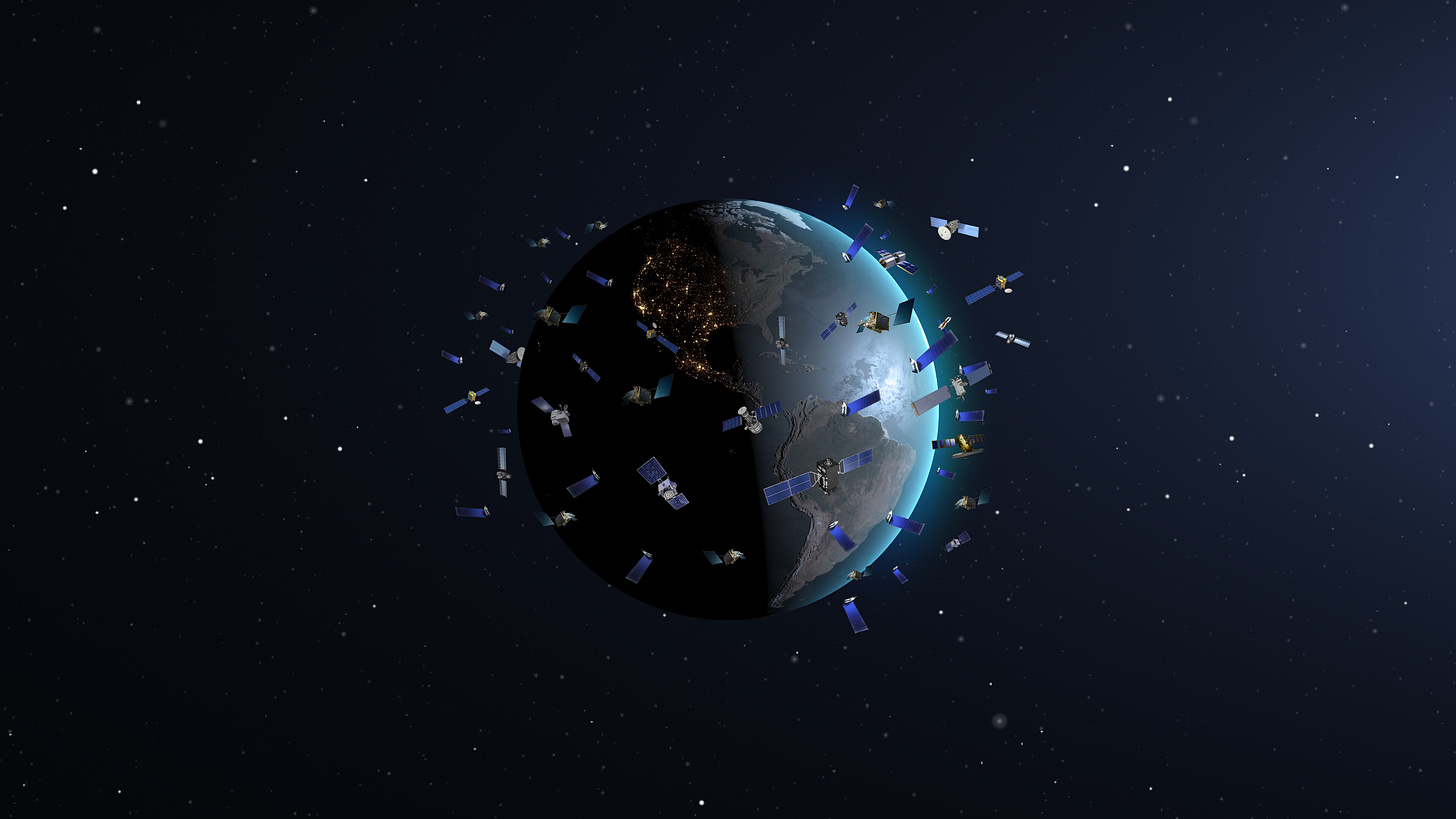

This week, China launched the first batch of satellites for what is expected to be a 14,000-strong mega internet satellite constellation.

Known as G60 and set for completion by 2030, the constellation is operated by the majority government-owned Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology (SSST) — one of several Chinese players currently jostling for a piece of the satellite network action. SSST, considered by some as the dark horse in the race, is now the first out of the gates with 18 satellites in low earth orbit.

English-language media coverage has framed China’s megaconstellation efforts as having the potential to directly “rival,” “take on,” “challenge,” and “compete” against Elon Musk’s Starlink. Chinese media, too, has consistently dubbed the country’s incipient internet satellite network as “the Chinese version of Starlink.”

But the simple head-to-head comparison belies a more complex set of dynamics. At core, China’s approach to technology development and deployment treats specific technologies not as standalone factors, but constituent pieces of a larger state-led industrial ecosystem.

Take drones: where Washington is zeroing in on potential threats from Chinese unmanned aerial vehicles, Beijing is building a whole “low altitude economy.”

Or consider AI: while headlines largely focus on comparing US and Chinese LLMs, China is positioning for the wholesale deployment of industrial AI to amplify its manufacturing dominance.

The same goes for Starlink. China is not simply looking to rival the US with its own satellite internet constellation. Rather, “China’s Starlink” will plug into a wider telecommunications infrastructure, positioning Beijing to establish a dominant lead in the emerging 6G era. This will have broad geopolitical and commercial implications — far greater than what a Starlink-focused framing would suggest.

Satellites and the 6G race

The coming 6G age is poised to change wireless technology. It promises hyperconnectivity between human, digital, and physical domains. Networks will become sensors: signals from objects will be integrated with networks, allowing instant identification and positioning of all sorts of devices, like cars and factory robots. And 6G will both power, and be powered by, AI. Countries and companies that can shape this new telecommunications era will reap vast technological and market sway.

China, for one, is eyeing global 6G leadership. And it has a head start, thanks to its existing expertise in 5G network construction — in turn amplified by its capacity to build and launch low-earth orbit satellites.

(Source: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/P. Marenfeld/Wikimedia Commons)

“The development of low-orbit satellite communication systems based on 5G can lay the foundation for China to improve 6G technology and industrial competitiveness,” writes Chen Shanzhi of the state-owned China Information and Communication Technologies Group. By reusing key 5G infrastructure, technologies, and standards, China can push the frontier of mobile communications and simultaneously “reduce technical risks…use and share the economies of 5G scale to reduce cost, and achieve differentiated competition.”

That 6G lead — supported by China’s industrial foundation in satellite manufacturing and rocket launches— will translate into gains in other key sectors, including autonomous vehicles and intelligent manufacturing. For example, while Washington frets over data security risks from Chinese vehicle software, Beijing is working to define a new telecommunications architecture that will grant it asymmetric advantages over global data flows.

In short, even notwithstanding Starlink’s China dependencies, China’s megaconstellation efforts go far beyond rivalling Musk in providing global internet service. Beijing’s ambitions are grander and more comprehensive. By cultivating dominance in 6G networks, Chinese companies downstream of the telecom providers — including AI firms and automotive players — all stand to gain additional competitive advantages. Internet satellites are just one part of the picture.

—

And for excellent, in-depth coverage of China’s space industry, see these posts from China Space Monitor

- China’s Satellite Internet Race Breaks Wide Open

- The Dark Horse for Building China’s Starlink

- China’s Answer to Starlink (Nov 2023 Update)

—

Weekly Links

️ Baijiu and chips. The Chinese state-owned maker of burn-in-your-throat liquor is diversifying its business lines by investing in…semicondcutors. (Global Times)

️ Smoothing energy demand. Xinhua has a story on how China’s power grid is dealing with spikes in electricity use during peak summer months. Energy analyst John Kemp, formerly of Reuters, provides useful context and analysis. He writes:

“The most interesting aspect of this article is how China has been able to use its vast geographic extent and diversity coupled with long-distance transmission to manage local peaks in electricity demand. East-West diversity means daily peak consumption is not synchronised. Eastern load centres can pull extra power during the evening peak from western generation centres where solar output is still close to the midday maximum. North-South diversity means high summer temperatures arrive at different times. In May and June, cooler northern areas can supply electricity to already hot southern regions. In July and August, during the wet phase of the monsoon, abundant southern hydro generation can support increasing airconditioning demand further north.” (Xinhua, JKempEnergy)

️ Big plans for small businesses. Economists Dani Rodrik and Rohan Sandhu argue that industrial policy must targetmicro-, small-, and medium-sized firms to unlock their potential and unblock growth constraints. (That approach is part and parcel of China’s industrial strategy, as our research has shown.) (VoxDev, Force Distance Times)

(Photo via China National Space Administration)