Welcome to a/symmetric, our weekly newsletter. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric. To receive issues over email, subscribe here.

This week:

- How China innovates: A deep (but by no means comprehensive) dive into China’s innovation strategy, both in laboratories and on factory floors — and how it industrializes R&D to achieve strategic market power.

- Weekly Links Round-Up: Picking sides in the AI race, European firms struggle China, and Tesla’s next China steps.

How China innovates

A tired trope, popular around a decade ago, is that China can’t innovate.

That thesis was always dubious, and has since been roundly proven wrong — as Chinese exports of innovative new products like consumer drones and EV lithium-ion batteries can attest.

Nor is innovation only about inventing something new. Innovation comes in various flavors, as a Chinese Academy of Engineering scholar pointed out recently: basic research goes “from zero to one,” while what he dubs “applied amplification research” goes “from one to 100.”

It is the latter, application- and scale-driven innovation that China in particular excels at: finding ways to industrialize and commercialize cutting-edge R&D results. In turn, China transforms that scale into strategically valuable and financially lucrative market power.

A deep tech investor distilled this “one to 100” ethos in a recent comment to Eleanor Olcott of the Financial Times:

“Chinese companies are not good at fundamental tech itself. But they are very good at looking at industry trends, following whatever good comes out, and leveraging their engineering dividend to follow whatever has emerged in the US.”

Tech transfers vs. tech transformation

China has a term for this type of application-driven innovation: “tech transformation.” The phrase refers to taking R&D from labs and turning it into “new technologies, new processes, new materials, new products, developing new industries, etc.”1

Beijing sees tech transformation as key to achieving technological supremacy. Wang Tianyou, vice president of Tianjin University, wrote in the Communist Party’s flagship theoretical journal in December:

“…the transformation of scientific and technological achievements has become the main battlefield for scientific and technological competition between countries, which is reflected in the competition in the quantity, quality and transformation speed of scientific and technological achievements transformation, as well as the competition in the degree of commercialization and industrialization and market share of scientific and technological achievements.

In other words: Groundbreaking basic research is important. It is also risky and costly. By leveraging its manufacturing might, China can externalize those risks, focusing instead on industrializing proven concepts — then winning global market share as it achieves scale.

Tech transformation shares overlaps with another term that may be more familiar: “tech transfer,” which refers to“getting knowledge and discoveries from the laboratory to the general public.” When used in reference to China, it also often comes with an extractive connotation: the use of policies by Beijing to compel foreign firms to transfer tech to domestic firms in return for access to the Chinese market.

Without getting bogged down in semantics, it appears that China’s concept of tech transformation is more explicitly geared towards achieving industrial and commercial scale.

The Beijing Institute of Technology notes that tech transformation has “no completely corresponding term in foreign countries,” and uses the following graphic to explain the two terms:

Source: Beijing Institute of Technology (translations added)

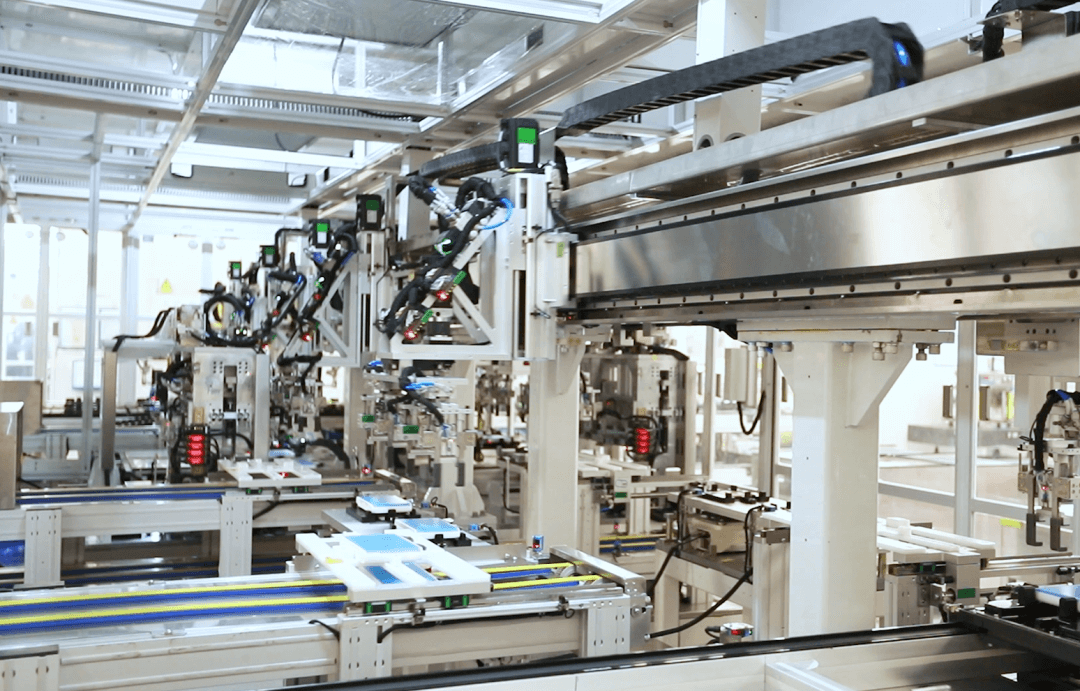

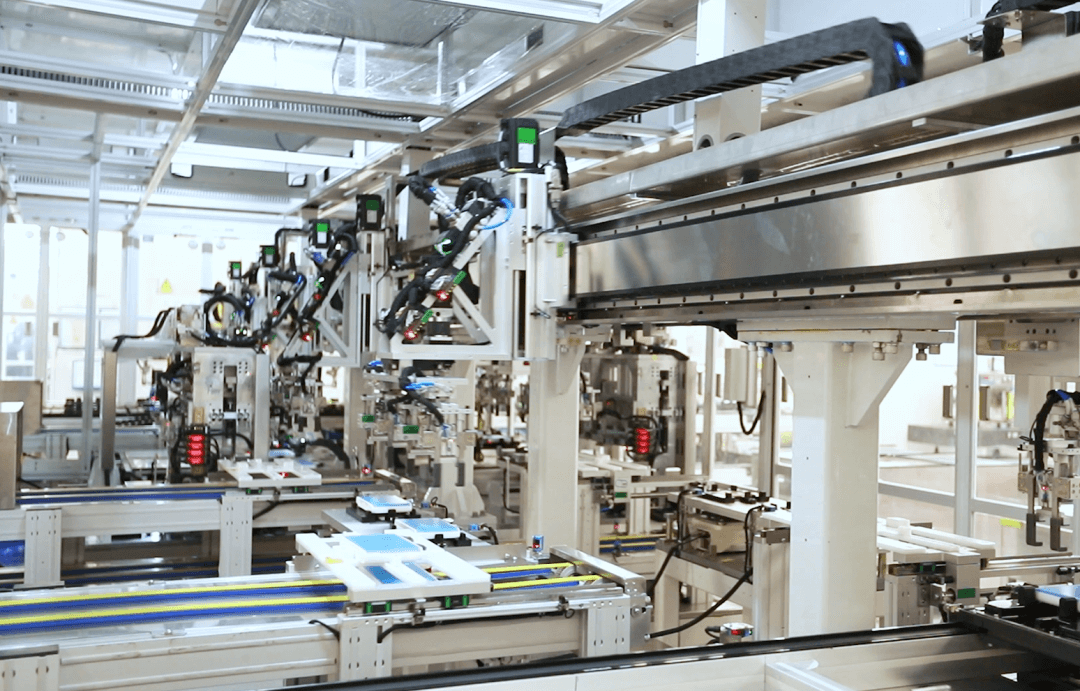

Innovating on the factory floor

Industrialization, of course, requires factories. And a lot of innovation in China happens on factory floors.

Chinese manufacturing expert Lin Xueping calls this “grayscale innovation:”2 the kind of innovation that happens on production sites when “engineers from different organizations collide with each other and improvise on the spot…At China’s manufacturing sites, there is a lot of innovation, but many technologies have not been translated into patents.”

One example of such “grayscale innovation” is wind turbines.

As Lin tells it, the German company Vensys Energy pioneered a new gearless wind turbine. Compared to existing wind turbines on the market, Vensys’ innovative design was structurally simpler, more efficient, cheaper, and less prone to malfunctions.

There was only one problem, according to Lin: Vensys struggled to manufacture and bring its product to market, in part because the market was still accustomed to wind turbines with gear boxes.

Along comes Chinese wind turbine maker Goldwind.3 In 2003, Goldwind licensed technology from Vensys. In the years following, the two firms worked closely to develop turbines, including improving the production efficiency of protective coatings. The next step was building a supply chain to industrialize Vensys’ technology. Lin writes:

“Developing supply chains is actually a huge innovation, and it is also an innovation that is easy to be ignored. In fact, all the standards taken from Germany are rigid standards. How do the standards turn into tooling, and how do they turn into craftsmanship? There is much reinvention in the process.”

Eventually, in 2008, Goldwind acquired 70% of Vensys. Today, Goldwind is the world’s top supplier of wind turbines. The company boasts that its gearless turbines are “shaping a new standard in wind technology” and “[boost] Goldwind’s advantage.”

Industrializing innovation

China is not the first to industrialize a competitor’s invention – and then eat that competitor’s lunch.

That honor likely goes to Germany, which in the late 19th century industrialized a young British chemist’s dye-making invention, and several years later beat the UK and France to dominate the global production of synthetic dyes. The number of dye firms in Germany quicky surpassed that of the UK and US:

Johann Murmann, Knowledge and Competitive Advantage, Cambridge University Press (2009)

Many factors led to Germany’s dye-making success, but at core its achievement boiled down to taking basic scientific research and then industrializing to achieve scale. As the historian Georg Meyer-Thurow put it: “Invention was industrialized.”

Today, China sees huge strategic value in industrializing invention. And it has major advantages, chief among them a large market in which to scale applications and “transform cutting-edge technology into future industries,” as a researcher at a state-linked think tank wrote recently. Meanwhile, it is also doubling down on basic research. China is gearing up for a lot of innovation — both in laboratories and on factory floors.

Weekly Links Round-Up

A lighting round this week given the longer-than-usual piece up top.

️ Saudi Arabia AI Fund Would Divest From China If US Asked, CEO Says. From the article: “US officials have told their Saudi Arabian counterparts that they need to choose between Chinese and American technology as they aim to build out the Saudi Arabian semiconductor industry…as part of ongoing talks on a range of national security issues.” (Bloomberg)

️ European companies in China are under pressure from slower growth, overcapacity. (CNBC)

️ Coming soon to China: Tesla’s “Full Self-Driving”? State media notes that Chinese officials signalled their eagerness to facilitate Tesla’s robotaxi tests in the country. Chinese industry players are excited: “promoting the application of FSD in the Chinese market is expected to achieve new breakthroughs in the intelligent connected vehicle industry chain such as driverless taxis.” (Reuters, Shanghai Securities News)

(Photo via Wuhan Municipal Government)