Welcome to a/symmetric, our weekly newsletter. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric. To receive issues over email, subscribe here.

This week:

- Can you industrial policy your way to innovation? A look at the case of China.

- Weekly Links Round-Up: Rebrand and evade. South Korea gets its own NASA. Plus: rewiring America’s electricity system.

Can industrial policy spur innovation?

China’s official proclamations make clear one of its key goals: the country must “seize the commanding heights” of science and technology and become the “high ground of innovation.”

Will it succeed?

The argument put forward in an essay this week by George Magnus of Oxford University’s China Centre is a resounding no.

The Chinese Communist Party, he writes, “persistently conflates industrial policy with innovation, which are not the same thing.” Though it has created “technological islands of excellence” and fostered “the rise of powerful companies,” Magnus argues that China “cannot create a true climate of economic innovation.” He blames Beijing’s penchant for state intervention over free market competition, and its weak legal and regulatory institutions. Plus, industrial policy is unlikely to fix China’s systemic economic problems.

It’s a compelling argument and one to take seriously — if regrettably flattened somewhat by its headline:

Source: Foreign Affairs

Yes, China innovates

But, as we argued recently, China has in fact proven highly adept at innovation.

For one, conventional measures of innovation capacity, like patent registrations and academic papers published in top journals, are only partial reflections of innovation.

Plenty of innovation happens on factory floors. A lot of tacit knowledge is created and accrued in the process of making stuff. Figuring out how to industrialize an original invention (whether your own or someone else’s), iterating a manufacturing process, and piecing together a robust supply chain to scale production, is itself an intensive exercise in innovation.

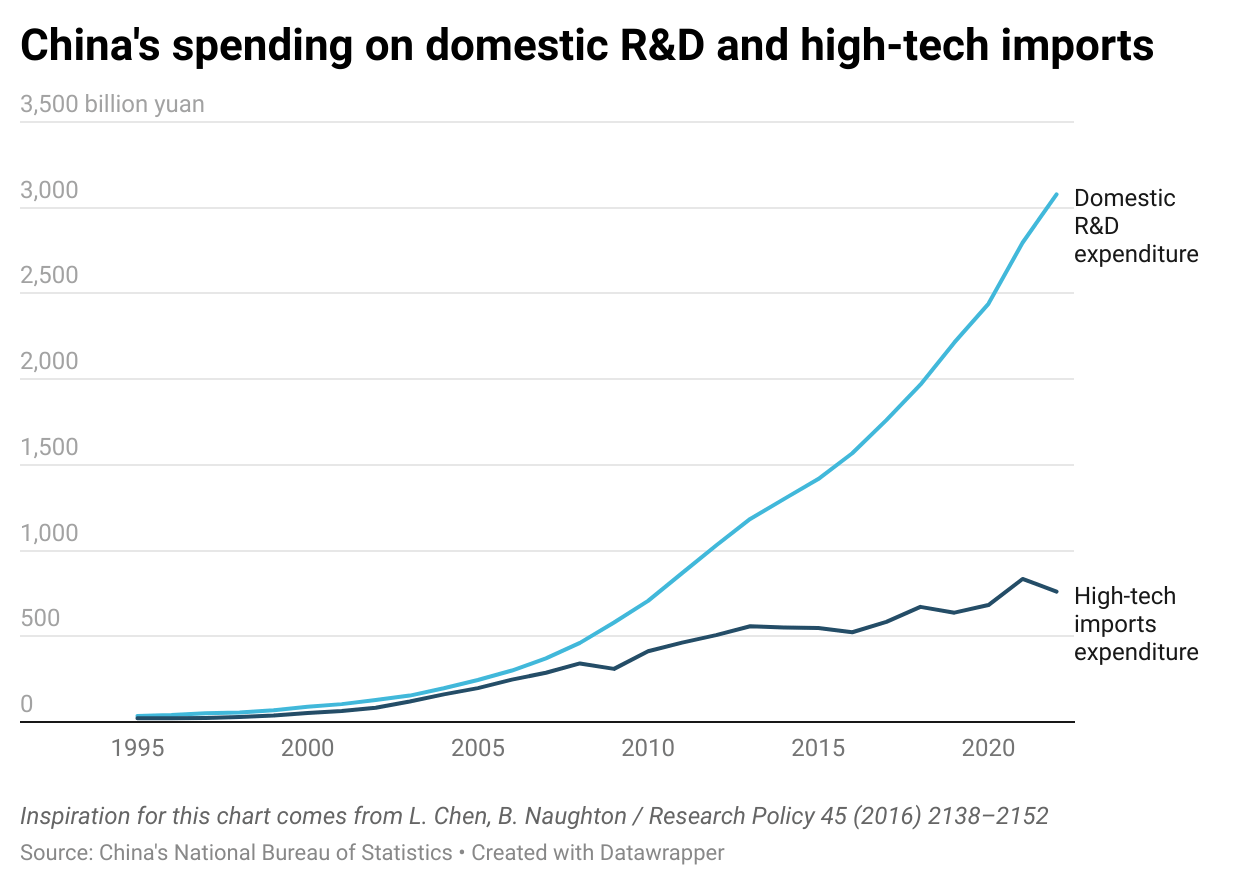

Plus, consider the fact that over the past two decades, growth in China’s domestic R&D spending has far outpaced expenditure on foreign technology imports. The chart below isn’t proof of innovative capacity per se, but it does show that China is investing heavily in innovation — and that the effort appears to be paying off.

We could also compare Chinese firms’ spending on foreign versus domestic technology.

Through 2017, Chinese industrial enterprises spent about twice as much on acquiring foreign tech as they did on buying domestic technology. That changed in 2018: for the first time, spending on foreign tech acquisitions (46.5 billion yuan) exceeded that for domestic tech (44 billion yuan). That gap widened further in 2022.

Innovate, create, dominate

Arguably, the two charts above show that China is innovating — at the very least, enough to reduce its reliance on foreign innovations.

How much of that is creating original inventions and pathbreaking research, versus merely closing a gap with foreign tech? Hard to say. But even the endeavor of catching up with foreign competitors, including by doing things more efficiently or cheaply, itself requires innovation.

And as important as innovation is, so is the ability to actually reap the value of those innovations.

To give some oft-cited examples: the US invented solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, and powerful rare earth permanent magnets — but China now dominates global production of all three.

Innovation loses some of its lustre if a rival ends up reaping all the rewards.

Related reading:

Why China still can’t make ballpoint pens

Weekly Links Round-Up

️ Blacklisted Chinese companies are rebranding to evade US restrictions, reports Heather Somerville. One upshot: “You should not be sanctioning individual firms, you should be sanctioning technology sectors,” says Derek Scissors, formerly of the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission. (Wall Street Journal)

️ South Korea launches its own NASA. Dubbed the Korea AeroSpace Administration (KASA), the new agency aims to build up the country’s commercial launch and satellite capabilities. (Science)

️ The US needs to its electricity system. Otherwise, America’s surge in clean energy investments “will not deliver its full economic and planetary potential,” writes Brian Deese, former director of the White House National Economic Council. The biggest obstacle to clean energy in the US is no longer insufficient demand; it’s “the structure of our electricity markets: the way we produce and consume electricity in America.” (The Atlantic)