As concerns over supply grow, food nationalism rears its head

Already massively inflated, wheat prices surged even higher this week after India, the world’s second largest producer of wheat, banned exports of the grain amid lower yields caused by a recent heat wave. Concerns over global food shortage are rising, a function of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and extreme weather events. India’s move constitutes a worrying signal that critical producers might adopt protectionist policies of food nationalism, as countries like China stockpile supply. And while the United Nations reports working to restore Ukrainian wheat shipments, that risks being easier said than done: Already, Russia’s capture of Mariupol has extended the blockade of key ports along Ukraine’s southern coastlines, stopping crucial wheat supplies from being exported. It looks increasingly likely that the world is staring down the barrel of full-blown, years-long food crisis that tips tens of millions into mass hunger and famine – and that turns food into a geopolitical battleground.

The US needs more energy, but oil and gas companies want dividends

US oil companies are flush with cash, thanks to soaring oil prices. But so far, they remain stingy when it comes to increasing production, despite the Biden administration’s exhortations to boost output amid global energy crisis.

In large part, this is a function of pressure to maintain capital discipline. After years of losses, investors want dividends and buybacks. They don’t want the kind of runaway capital spending that would be necessary to ramp up production – even if that is what the larger economy needs. This poses a problem: the US needs to increase oil production stat, but oil companies’ immediate commercial interests discourage them from doing so. This is effectively the same mismatch that creates failing infrastructure in the US, as well as inadequate investment in critical minerals and other upstream resources. That said, the government does have tools at its disposal that could help address the problem: Washington could leverage the Defense Production Act to ease supply chain bottlenecks for inputs like steel pipes and fracking sand. Washington could also work to influence oil and gas companies’ longer-term market incentives, using the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to encourage production by guaranteeing demand, say — and signaling that it will not clamp down on oil and gas production the moment today’s energy crisis passes.

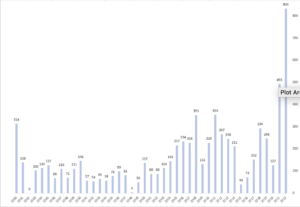

Total free cash flow for public exploration and production companies, USD billions

Source: Rystad Energy

While China enjoys the luxury of cheap Russian oil

Meanwhile, China may be flush with cheap energy. The country continues to import from Russia – and Russian crude oil has been trading at a steep discount relative to Brent and WTI since sanctions hit following its invasion of Ukraine. Bloomberg reports this week that Beijing is in talks with Moscow to buy cheap Urals crude with which to fill up its strategic petroleum reserves. And Beijing will likely want to snap up more cheap Urals, too, as domestic demand rebounds from weeks of covid lockdowns. This is a perfect situation for Beijing, as it walks the tightrope between Russia and the West: China gets cheap oil as the rest of the world runs out of energy; it does so subtly, without pushback from a distracted, confrontation-averse West. In fact, the US is easing the path for China. Washington has said that Chinese purchases of Russian oil to replenish reserves would not violate its sanctions.

From shortage to switch: Less palladium means more platinum

The critical minerals story of the past months has been one of shortage imposed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Now, as that reality settles in, markets are, where possible, adjusting to the new normal – and, in the process, transforming both technological and geo-economic trends. Russia accounts for over 40 percent of global palladium mine production, a key input into gasoline-engine catalytic converters, among other things. But in many use-cases, palladium is effectively interchangeable with platinum. And Russia produces only about 10 percent of the world’s mined platinum. Now, carmakers are accelerating a switch from palladium to platinum. The WPIC forecasts further platinum-for-palladium substitution given the former’s lower risks of supply disruption, as well as significantly lower prices. That said, platinum may not be a panacea: A spike in demand for the metal could crimp supplies in the short run, pushing the market into a deficit this year.

The US invests in silicon carbide chip production (kind of)

Late last month, the US semiconductor manufacturer Wolfspeed opened the country’s first major silicon carbide chip plant in New York. Silicon carbide chips, which promise greater battery efficiency, are increasingly being adopted in automotive applications: By 2027, autos are projected to make up 80 percent of a $6.3 billion silicon carbide market. The New York governor hailed Wolfspeed’s new plant as the harbinger of a “Silicon Carbide Valley.” That said, this plant does not address the question of where silicon carbide to make the chips is coming from: China is the world’s largest producer of silicon carbide globally, constituting approximately 70 percent of the global total. The US contributes about 3 percent. An even more extreme story holds for gallium nitride, which like silicon carbide is part of the wide bandgap family of semiconductor compounds that can move more power more quickly than just silicon. China currently makes up over 97 percent of global gallium production.

(Photo by Pexels)