A necessary input into everything from passenger airplanes to kitchen appliances, aluminum is one of the foundational industrial materials of modern society. And, as with so many other important products and materials, America’s capacity to produce primary aluminum has dwindled to a perilously low level.

This is a danger. It is also an opportunity. There is an opportunity for America to take a leading role in more cleanly produced aluminum as part of a long overdue revival of domestic manufacturing. But seizing this moment requires the US government to pursue the right incentives and investments to make domestic aluminum production commercially viable again – despite its energy intensiveness, and as aluminum demand grows over the decades ahead.

The demand for aluminum will only grow, and grow faster, as the US economy transitions to mass adoption of electric vehicles and other clean energy systems – nearly all of which require increasing amounts of aluminum.

The case for action is clear. Aluminum is critical to economic and national security due to its defense, aerospace, electricity, and transportation uses. Notable military applications include armor plates for vehicles, aircraft structural parts and components, naval vessels, space and missile components, and propellants. And in the commercial and industrial space, aluminum is the most effective option for high-voltage long distance transmission lines – therefore necessary to keep lights on and factories humming. It is three times lighter and less than a third of the price of copper.

And this just scratches the surface of aluminum’s significance.

The demand for aluminum will only grow, and grow faster, as the US economy transitions to mass adoption of electric vehicles and other clean energy systems – nearly all of which require increasing amounts of aluminum.

The US government recognizes as much. The Biden Administration deems aluminum a “strategic and critical material.” The Commerce Department labels it “essential.” The Department of Defense identifies it as “a material of interest.”

Yet despite that awareness and even as demand for aluminum climbs, US domestic production continues to drop. Predatory Chinese trading practices were a major factor in reducing the US primary aluminum industry from nearly 40 smelters in the early 1990s – when the US led the world in primary production – to seven at the start of 2020. That number has dropped even further over the past three years to five after the closing of the Century Hawesville facility in Kentucky, which was the primary source of high-grade aluminum to the US military. Now the Middle East and China are the major producers of high-purity aluminum.

The United States has the benefit of being ahead of a potential supply shock coming in aluminum. Now, the United States needs to do something about it.

The main obstacle to a US aluminum resurgence is the cost of energy. The amount of electricity to produce aluminum exceeds that for any other comparable materials. And the price of electricity across the country spiked after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and remains high. Energy costs were the main factor leading to the Kentucky plant’s closure. Last year there was a serious effort – involving state and local governments, unions, and private equity– to reopen a primary production facility in Intalco, Washington, which closed in 2020. But the deal floundered, in large part because it lacked a long-term electricity contract with the Pacific Northwest’s main utility.

The US predicament with respect to aluminum is mitigated significantly by having a major – and friendly – producer of clean primary aluminum to the north. However, even Canada’s market share is less than five percent. By comparison, China and Russia combined control more than 60 percent of the world’s aluminum production. The US portion is about one percent. And Canadian primary aluminum production is not expected to increase, meaning that US reliance on less reliable and potentially hostile countries will continue to grow, even as these countries’ own domestic demand increases, further exacerbating the global supply squeeze.

Ultimately, the future of the domestic primary aluminum industry depends on reconciling the demand for energy and industrial security with the imperative to de-carbonize more of the US economy. Aluminum production emits carbon directly in its smelting process and through its use of fossil fuels energy inputs. Yet aluminum use is crucial for the clean energy transition. For example, EVs require 42 percent more aluminum per vehicle than non-EVs.

Lowering and stabilizing the costs of electricity from non-coal sources – solar, wind, nuclear, and, especially, hydro-electric power – is essential to achieving both secure access to affordable aluminum supplies and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The clean energy transition’s influence on energy prices and innovations, as well as the additional demand it generates for primary aluminum create a paradox. Wood Mackenzie analysts have termed this “aluminum’s energy transition circularity.” The rate at which the aluminum industry can reduce emissions at scale is a function of the buildout and availability of lower-carbon energy sources, which themselves require – are a function of the use of — low-carbon aluminum.

Solving this circularity problem is of the utmost importance. The US needs to decarbonize energy-intensive aluminum production, specifically primary aluminum, to ensure economic vitality. Doing so demands incorporating innovations in the smelting process and securing electricity from renewable energy sources. However, it must be done quickly enough to keep pace with the clean energy transition, which is driving rising demand for aluminum, and increasing global competition.

The success of these efforts will be a key determinant of future production trends: specifically, which country has the production capacity to supply the additional 40 million metric tons of additional primary demand through 2050 and do it in a low-carbon way.

The United States has learned firsthand how supply chain vulnerabilities can send shock waves through the economy. In 2021, a shortage of semiconductors (and commensurate price increases) cost an estimated one percent of GDP because of stalled production, especially in the auto sector. To overcome US deficiencies in semiconductors, battery minerals, and other crucial sectors, the US Congress has appropriated upwards of 1 trillion USD between the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS Act, and Inflation Reduction Act.

The United States has the benefit of being ahead of a potential supply shock coming in aluminum. Now, the United States needs to do something about it.

The IRA, for example, allocates funds to bolster clean production for “strategic materials.” Billions have also been allocated for grid security. But America’s cumbersome and outmoded permitting process makes completing new projects – to generate electricity or transport it – a decade-long endeavor. Reforming federal permitting laws would be a particularly good start.

There is a real – albeit narrow – opportunity to ensure the United States can access and afford the aluminum it needs to power our economy and secure our national security. Government and industry must be ready to take the plunge together.

Joe Quinn is the Vice President at the SAFE Foundation and Director of the Center for Strategic Industrial Materials. Aluminum is vital to the transition to a more sustainable energy future as a key material in green technologies from electric vehicles to solar panels. A strong North American production sector could become the cornerstone of an innovative manufacturing ecosystem benefiting automakers, defense contractors, packaging firms and other industries.

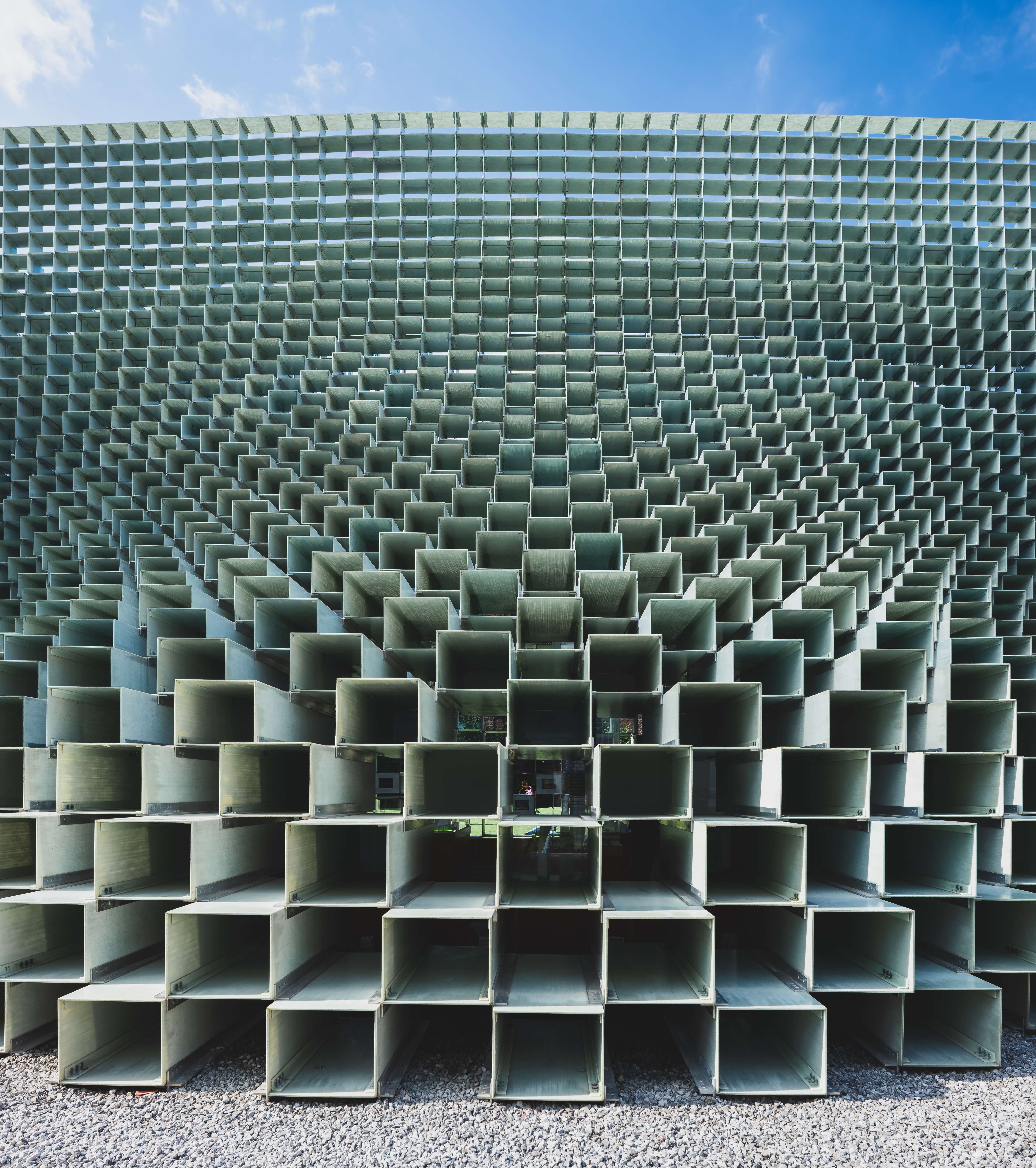

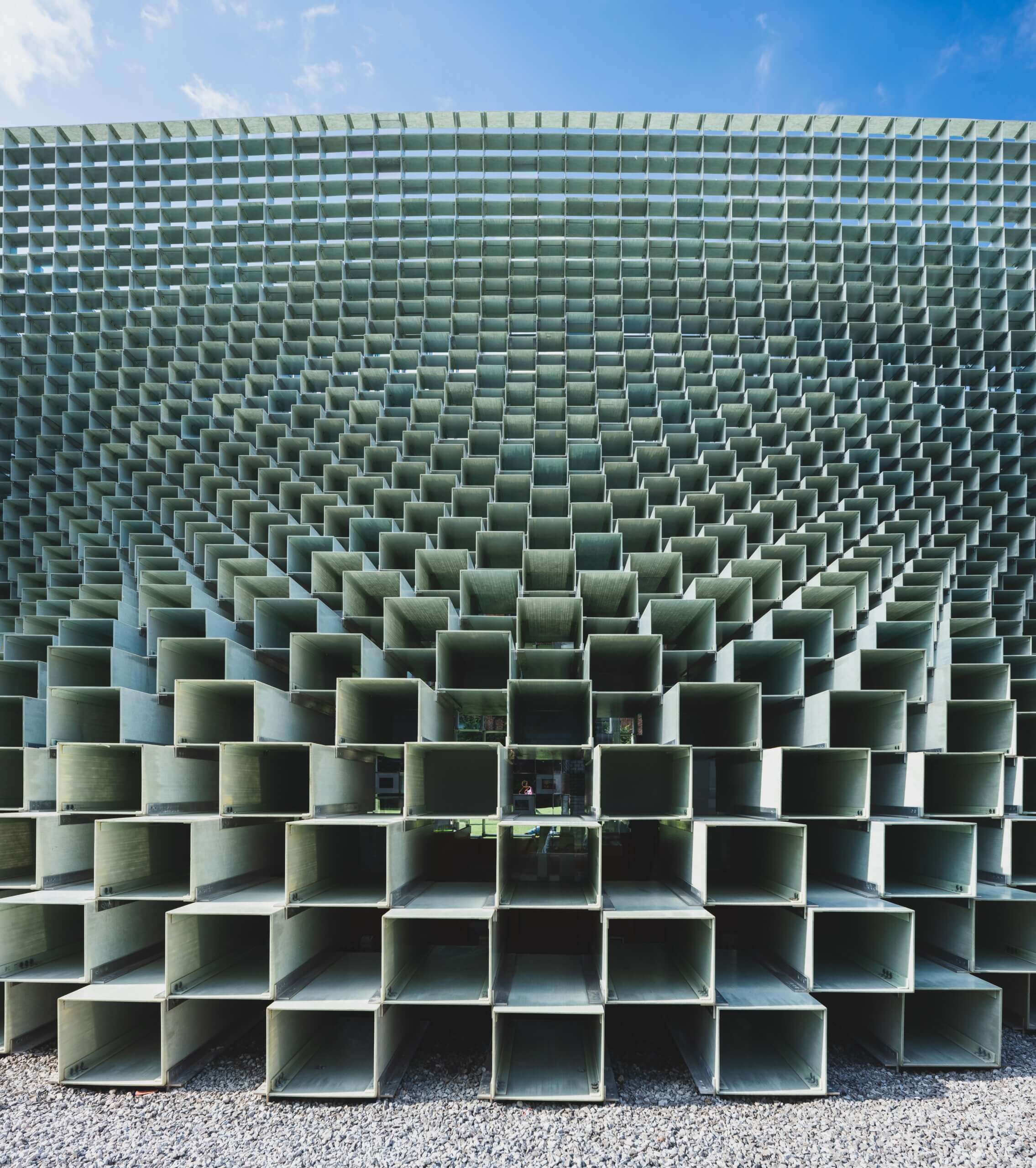

(Photo by Scott Web/Pexels)