In the nascent Indonesian new energy industry, the west risks financing China’s profit, and control. Plus, in factors: Enel builds a solar panel plant in the US but China still dominates the value chain; lithium stays hot; and the price cap on Russian oil nears, but with what consequences? While in markets, LNG prices resist demand, Japan’s economy shrinks, the UK does austerity – and stray missiles plus wheat uncertainty threaten to disrupt it all.

THE BIG IMBALANCE

Indonesia’s energy transition: who foots the bill, and who reaps the rewards?

The US, EU, and a number of other countries this week signed a 20 billion USD plan to help Indonesia transition away from coal. It’s reportedly the biggest climate finance deal ever signed. The aim is to see Indonesia peak its power-sector emissions by 2030, and have renewables make up 34% of all power generation by then. On top of that financing commitment, Indonesia this week signed a 300 million USD pact with the Asian Development Bank to refinance and retire a coal-fired power plant.

Concurrently, Indonesia is ramping up investments in the EV battery industry, which will help it both power and benefit from the energy transition. On the same day as the ADB coal plant retirement deal, Indonesia’s sovereign wealth fund announced a 2 billion USD fund to invest in the EV value chain.

But here’s the rub: The two other main partners in the fund are the Chinese battery giant CATL, and the global arm of China Merchants Bank. While western countries help to finance Indonesia’s pivot away from coal, Chinese firms and state entities are staking out influential, and potentially lucrative, positions in the emergent industry to be built off that pivot. Is the west financing China’s profit – and control?

For more on the larger context of this reality – and a proposal for redressing it – read commentary we published this week from EU Parliament member Reinhard Bütikofer on how Europe, and with it the US, can use today’s geopolitical crisis to refocus international economic policy around production; in short, how the west can turn narrative, commitments, and dollars into action.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSEnel builds a solar panel plant in the US

Enel, the Italian energy giant, plans to set up a massive factory in the US with the capacity to produce up to 6 gigawatts of solar panels per year. The factory would also manufacture solar cells, components that make up solar panels and which the US currently does not produce.

It’s a welcome and necessary development — but nowhere near sufficient. Move up the supply chain, and production of upstream inputs like polysilicon, wafers, ingots, and wafers is still dominated by China. Further downstream of solar panels, China also dominates. Take PV inverters, which convert the current output from solar panels to a current that can be fed into the electric grid: Three Chinese companies make up 51% of global market share.

Even lithium slag waste is in high demand

Is demand for lithium finally showing signs of cooling? Hardly. Spot prices for lithium carbonate in China edged slightly lower this week to notch the first decline since June. But keep in mind two things: First, China’s first-quarter demand is always relatively soft; more importantly, the macro reality is that lithium demand is still forecast to far outstrip supply in years to come. In fact, lithium prices continue to hit such high levels that Chinese ceramics producers are now deeming it economically viable to move into lithium processing. China’s state-run Securities Daily reported this week that domestic companies are fighting over what would previously be considered low-value lithium slag waste, which can be processed into a stock for further conversion into lithium carbonate.

India, China, and oil price cap blues

The looming US- and EU-imposed price cap on Russian oil, set to take effect on December 5, has Chinese and Indian refiners scrambling to assess the risks of sanctions versus the need to secure supplies.

The two countries are the world’s largest and third-largest crude importers. They have become major buyers of Russian oil since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Disruptions to Russian crude supplies — especially if Moscow refuses to sell crude oil at the capped price set by the US and EU — could hit India particularly hard, given its high import dependence and price-sensitive consumers. Indian refiners have already become wary of buying Russian oil.

Beijing seems more sanguine: Chinese state-owned refiners are reportedly considering workarounds, including increasing the volume of Russian oil transported via pipelines and setting up a separate banking entity to handle payments with Russia. The other option, of course, is to buy Russian oil at or below the US-EU price cap. But neither India nor Beijing has supported that policy.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

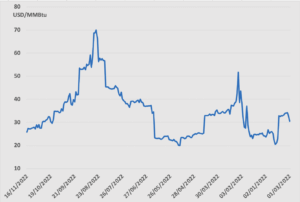

MARKETSLNG prices are falling…for now

LNG prices typically rise as winter beckons. That usual pattern doesn’t seem to be holding true this year. Weekly spot prices of JKM contracts, the LNG pricing reference point for North Asia, have been trending down even as demand rises.

Why? One reason could be the high natural gas inventories in Europe (currently more than 95% full) and Japan (utilities currently have 36% more gas in storage than the five-year average). Another reason is expectations of a relatively warm start to the winter.

Of course, this could be a temporary anomaly. Prices may well begin to rise alongside demand. Europe’s November LNG imports, for example, are set to hit near-record levels. Add to that the fact that European buyers are unwilling to sign the kind of long-term, 15- to 20-year contracts that would help suppliers sell at lower prices. Plus, there’s the chance that the US could cap LNG exports – which would send global prices up. US industry players are largely opposed to such curbs. But other countries have proven ready and willing to curtail exports. Take Uzbekistan, which essentially ceased all natural gas exports to China and other Central Asian nations this week amid a domestic fuel crunch.

The bottom line: LNG prices may be trending down now, but volatility is still high.

LNG Japan/Korea Marker PLATTS Futures

Source: CME via Investing.com

Japan’s economy shrinks

Japan’s economy unexpectedly contracted in the third quarter, shrinking 1.2% from the previous year. It’s the first contraction Japan has seen in a year, and comes as the country grapples with surging import bills caused by the weak yen. High import costs have pushed inflation to a 40-year peak, with the core CPI (excluding food and energy) up 3.6% from a year earlier, exceeding the 3.5% forecast by economists and the 3% gain notched in September. Still, the Bank of Japan is sticking to its dovish stance, betting that consistently hitting inflation targets will finally get the country out of its deflationary rut. And there are reasons for optimism: The return of tourism can drive growth, as will the government’s 200 billion USD stimulus package and the continuation of ultra-loose monetary policy.

The UK does austerity

The British government has a 55 billion pound (66 billion USD) fiscal plan to restore the country’s economic credibility: 30 billion pounds in spending cuts and 25 billion in tax hikes. The measures were unveiled by finance minister Jeremy Hunt, who said the government and the Bank of England are now working in “lockstep” in a bid to reassure markets — a not so subtle dig at the disastrously short-lived Truss-Kwarteng duo. The pound fell and gilts sold off after Hunt’s announcement.

Still, one good sign from the markets is that the so-called “moron risk premium” — the extra cost the UK has to pay to borrow money because of its leaders’ reckless decisions — has now essentially been reversed, as the falling spread between British and French 10-year yields can attest. But very real struggles lie ahead: Household incomes are forecast to dive by 7% in the next few years, and living standards are set to fall by the biggest margin on record.

UK 10-year gilt, spread over French 10-year bond, %

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSA missile strikes a Polish village close to the Ukrainian border

The risk of the Russia-Ukraine war spilling over into neighboring countries and potentially triggering NATO mobilization was averted this week as leaders of Warsaw, Washington, and the north Atlantic alliance said that a missile that killed two in Poland was unlikely to have been fired from Russia, and was more likely strays from Ukraine’s air defenses.

Still, the close call raised global alarm that the Russia-Ukraine war could spiral into a much larger military confrontation. For now, an investigation is underway, with experts from Ukraine, Poland, and the US probing the events leading up to the blast. Meanwhile, Russia continues to rain down missiles on Ukraine, crippling half of the country’s energy system.

Wheat uncertainty is here to stay

The good news: the United Nations-brokered Black Sea grain export deal between Ukraine and Russia has been extended by 120 days. The original deal, struck in July, has allowed some 11 million tons of Ukrainian grain to be shipped out of Ukraine’s ports. Those grain cargoes have reached markets in Asia, Europe, and Africa, helping ease food prices in a tight global market. When Russia flipped-flopped on the deal last month, wheat and corn prices spiked; now, with the deal extended, grain prices have moderated slightly.

The less good news: Uncertainty remains. There’s nothing stopping Moscow from weaponizing the grain deal to make its own demands, such as increased Russian fertilizer exports. And the global wheat market will continue to remain volatile. The CEO of Australian grain exporter GrainCorp said this week that supply threats caused by the war in Ukraine will lurk for at least another two to three years.

(Photo by Braeson Holland/Pexels)