Argentine soybean production has imploded. The implications have not yet begun to play out. But they will, and will define global protein meal markets in the second half of this year.

Argentina is the world’s fourth largest producer of soybeans, accounting for more than 10% of global supply, and largest exporter of soybean products. But historic drought in the country is devastating its production, with serious consequences for global supply. And those consequences are not currently being priced into markets, exacerbating the problem.

Argentina is the world’s fourth largest producer of soybeans, accounting for more than 10% of global supply, and largest exporter of soybean products. But historic drought in the country is devastating its production, with serious consequences for global supply.

The US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Buenos Aires-based agricultural attaché published the first “official” forecast for this year’s crop nearly 11 months ago, estimating 51 million metric tons of soybean production out of Argentina. That estimate made sense given the country’s production history, which has averaged about 48 million metric tons over the past four years.

But in February, the USDA’s economists adjusted their forecast to 41 million metric tons. And in last week’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), they once more trimmed their estimate, this time projecting 33 million metric tons of Argentine soybean production for the year. The very next day, Argentina’s Rosario Grain Exchange issued their own forecast, projecting that the soybean crop for the year would be about 27 million metrics tons, 6 million metric tons lower than the USDA. Many knowledgeable private forecasters are estimating a crop size of 25. The Buenos Aires Exchange at the end of last week estimated the crop at 25 million metric tons down from their previous estimate of 29.

Remember: All of this started at 51.

What does this Argentine crop disaster mean for the price and availability of global protein meal supplies? What are scenarios that could unfold? The global soybean balance sheet has moved from bloated to slim in 60 short days. And markets are not pricing in the severity of the situation, a reality that risks preventing correction, and therefore exacerbating strains on global soybean supply.

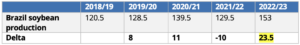

Source: USDA; Unit: Million metric tons

Consider the above data table, which outlines what the market has been focused on. Big in the press: The highlighted yellow box above, the 23.5 million metric ton year-over-year expansion in Brazilian production. This is a tonnage record. It has received major acclaim and focus from global oilseed traders. “Wow,” they exclaim, “look at the size of that crop…it is huge!” No disagreement there. It’s true: Brazil’s production is huge.

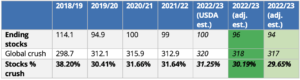

But now, let’s put the “huge” into perspective. Let’s look at the below table, which points to what the market has not paid attention to. Here, I will focus on the relationship between two USDA statistics: “Crush,” or the processing of soybeans into the two primary components soybean meal and soybean oil, and “ending stocks,” or the available soybeans at the end of September that remain in storage as soybeans and not crushed (often referred to as “carryover” as in carryover to the next crop year). We grain and oilseed traders like to express ending stocks in relation to demand (in this case crush) so we can put the ending stocks into perspective relative to other years, as we generally forecast prices with a view to ending stocks and the stocks-to-usage ratio.

Source: USDA, Cronin; Unit: Million metric tons

What we observe in the above table is that the USDA’s current forecast for global soybean ending stocks sits at 100 million metrics tons. Divided by a global crush forecast of 320 million metric tons, that yields a ratio of 31.25% stocks to demand ratio. Looking at other years, we can observe that 31.25% is pretty normal, not that special. The “huge” Brazilian soybean crop will get consumed and will not lead to burdensome supplies. Get it? The global oilseed trade cannot stop talking about Brazil’s “huge” production, but the reality is that the record crop will not yield excess available supplies compared to past precedent. Supply levels will be normal. In other words, removing the numbers and jargon: Global food security did not increase with the Brazilian record production. It remained the same.

Now, developments in Argentina not only bring the global “surplus” back to a normal level but also leave global ending stocks much tighter than they have been in recent years.

Now look at the green boxes. These are estimates after adjusting USDA data for global soybean crush and ending stocks based on Argentina’s imploding soybean forecast, as reflected in Argentine official resources (Rosario Grain Exchange) and private crop estimators. In the darker green box I reduce the global ending stocks by a conservative 4 million metric tons and the global crush by 2 million metric tons due to less available Argentine supply. Now the ending stocks ratio comes to 30.19%. In the lighter green box, I make even lower, less conservative adjustments to ending stocks and crush, and arrive at a ratio of 29.65% or the lowest available stocks relative to crush demand in 5 years.

Just months ago, Brazil’s record numbers had been interpreted to suggest the potential for global soybean surplus. Now, developments in Argentina not only bring the global “surplus” back to a normal level but also leave global ending stocks much tighter than they have been in recent years.

And most in the global oilseed trade – and agricultural industry more broadly – are not paying attention. Current 2023 prices are pricing the global soybean meal supply as if it were the same as a year ago. But it is not. This risks meaning that soybean prices aren’t going to rise sufficiently, therefore the market isn’t going to correct for Argentina’s implosion, and that the global soybean balance sheet will only tighten.

In an environment of agricultural resource scarcity driven by factors ranging from the war in Ukraine to extreme weather trends to geopolitical tension, Argentina’s soybean implosion is bad enough. A failure of the market to adjust for that takes the potential disruption from bad to worse.

Walter Cronin continues to pursue the build out of the US soybean processing industry since stepping down from his role as Chief Commercial Officer at Green Plains, Inc (NASDAQ:GPRE). The expansive demand from a growing and wealthier global population for vegetable protein meal to produce meat proteins drives this opportunity. Recent developments in US biofuel policy promote greater demand for soybean oil as a feedstock for renewable diesel, and also contribute to the need for expansion in US soybean processing capacity. Walter works with long term colleagues to provide economic feasibility analysis, financing, design, construction, operations, and commercial risk management for greenfield and brownfield capacity expansion.

(Photo by Aydin Photography)