The construction industry is as big as it is important. Without construction, our society would cease to be. We would have no ports, roads, or bridges. No cell towers, power grids, or water grids. No hospital, schools, or homes. Probably not a day goes by when you don’t interface with or benefit from some major capital works project. Virtually every human being on the planet is affected by the industry.

However, for all its size and importance, the industry is deeply, disastrously broken. Project after project comes in behind schedule and over budget; $1.6 trillion each year is wasted because of delays or cost overruns. Ninety-eight percent of megaprojects suffer from blown schedules and busted budgets. Projects are tied up in a byzantine snake pit of administration, bureaucracy, and fragmentation. It is amazing that anything gets built at all.

This is not just bad for business. It’s bad for humanity. Capital projects are feats of human ingenuity and engineering that make modern life worth living. When they don’t get built, we all suffer. And we all pay for it, in one way or another.

How did the industry become so dysfunctional? The problem is complex and multifaceted, but it revolves around one major blind spot: the industry fails to see projects as production systems that can be managed according to the principles of operations management.

Putting operations management front and center

The stakeholders have sidelined operations management as a marginal field that is relevant only during the postdelivery phase of a project. This is incorrect. Operations management, i.e., management of operations, is the answer to the fundamental question, “How do we actually get XYZ built?”

Putting operations management front and center in the process (rather than as an afterthought) is in contrast to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, published by the Project Management Institute (PMI).

…rather than focus on administration, we’re going to focus on production. Stop filling out forms, worrying about contracts, and writing each other emails, and concentrate on designing, making, and building things.

PMI regards operations management as a knowledge set outside of formal project management, something that comes into play after the asset is delivered. My argument, in contrast, is that it is the knowledge to actually deliver a project, because you’re taking inputs to make outputs. The utility of operations management in designing and building—production, in other words—has been given short shrift. To the detriment of literally everyone.

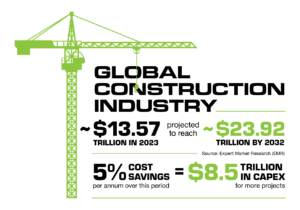

(Graphic from Built to Fail)

A brief history of capital project delivery

Ignoring operations management is so deeply rooted in industry practice in large part because the way we do things relies too much on outmoded, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century approaches to management and production.

Broadly, we can separate the field of capital project delivery into three eras.

Era 1, the era of productivity, was deeply influenced by Frederick Taylor and his principles of Scientific Management. Taylor attempted to revolutionize industrial efficiency and labor productivity, by separating planning from doing and rigorously measuring and tweaking each stage of the production process to boost efficiency. In the early twentieth century, Daniel Hauer applied Taylorism to construction. What did not work in manufacturing is also causing confusion in construction. The separation of planning and doing means that the two sides are fundamentally disconnected. You need a synergy of planning and doing to ensure projects are built well, on time, and on budget. Era 1 is by no means over—construction companies and the people running them are still stuck on Taylor/Hauer. While other industries have evolved, we are spinning our wheels.

Operations management is the answer to the fundamental question, “How do we actually get XYZ built?”

Era 2, the era of predictability, took shape in the late 1950s and 1960s and was preoccupied with the predictability of project outcomes. This was—and remains—the era of project management. Era 2 focuses on the administrative aspects of managing a project rather than designing and building. Consequently, the actual design, making, delivery, and installation is given short shrift. Instead, industry stakeholders fixate on how we organize the project, track the project, and motivate people. Project schedules created at the start of the project are used to track progress in a highly variable environment. Project managers must decide to update the schedule to reflect reality or continue to use the existing schedule to track progress.

The construction industry fails to see projects as production systems that can be managed according to the principles of operations management.

Another symptom of this dysfunction is severe fragmentation. Vertically, the owner who needs an asset built and the people doing the design, building, and engineering work is separated by many, many layers—resulting in competing interests and mismatched objectives and agendas. Horizontally, a given project requires a dizzying multitude of independent companies, contractors, subcontractors, and craftspeople, instead of all these functions consolidated under one roof.

The ability to effectively integrate and coordinate all this outstretches the capabilities of the methods and process used today. So all of us suffer from the shortsightedness and inefficiency of Era 1 and Era 2. The solution is what I call Era 3.

A new era: focusing on production

Era 3 is the era of profitability where the focus shifts from administration to production. It really began in the mid-’90s, when a few of us started breaking from the dominant models and introducing new ways of working. Era 3 is the hope for the future—but we’re far from realizing that vision.

That vision is this: rather than focus on administration, we’re going to focus on production. Stop filling out forms, worrying about contracts, and writing each other emails, and concentrate on designing, making, and building things.

For all its size and importance, the construction industry is deeply, disastrously broken. The good news is that the solutions are already there. We just need to implement them.

The vision of Era 3 also calls for embracing the exciting technologies like autonomous vehicles, robotics, high-speed networks, massive computing power, and emerging technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) and Internet of Things (IoT). These technologies have a place in construction, as they do in other industries.

The Era 1/Era 2 preoccupation with administration, contracting, risk analysis, and all those ancillary tasks causes the industry to ignore modern ways of getting things done. Technology could solve a lot of the logjams that make capital projects unnecessarily late and absurdly expensive. Administrative tasks can be automated. GPS tracking and IoT sensor will provide automated updates, replacing the need for an army of planners to predict when materials will arrive or playing telephone tag for an hour. The solutions are already there. We just need to implement them.

– Todd R. Zabelle has been involved in some of the world’s most complex and critical projects. He is one of four founding equity partners of the Lean Construction Institute (Ballard, Howell, Tommelein & Zabelle), Founder Project Production Institute, Founder & CEO Strategic Project Solutions, Inc., Founder & CEO Pacific Contracting (featured in the U.K. Rethinking Construction aka Egan Report) and Forbes Featured Author.

(Book cover courtesy of Todd R. Zabelle)