Indonesia’s Nickel Endowment Pushes It to Center Stage

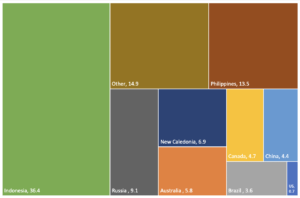

With demand for nickel rising, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine crunching supply, Indonesia has become a hot spot in the global EV competition. Indonesia is the world’s largest nickel producer and holds over a fifth of global reserves. (Note, however, that Russia accounts for 21.1% of mine production of Class 1 nickel—the only type used in batteries—while Indonesia makes up only 6.8%.) Accordingly, major battery companies are flocking to Indonesia in a bid to secure nickel supplies.

Many of those are Chinese. For example, Chinese battery giant CATL announced last week that it’s a investing $6 billion to build a mine-to-batteries facility in a joint venture with Antam and Indonesia Battery. This week, a consortium of South Korean, Chinese, and Indonesia firms – including Korea’s LG Energy Solution, China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, and Indonesian State-owned nickel miner Antam — announced a joint investment of some $9 billion in an end-to-end EV battery supply chain in Indonesia. Hyundai and LG are also building a 10 GWh EV battery plant in Indonesia.

But Indonesia does not appear content to let other, developed EV countries move in and assert control over domestic supply. Rather, the country is taking steps to move to higher value-add downstream segments of the supply chain itself. And Indonesia is having some success so far: After the government banned exports of unprocessed nickel ore in January 2020, exports of the higher value nickel pig iron rose sharply. Now, the government is considering imposing progressive export tariffs on nickel pig iron to encourage investment in Indonesia. With Indonesia’s policy of “resource nationalism” appearing to be paying off, other mineral-rich countries may be looking to do the same.

Mexico Nationalizes Lithium Mining – With Others Poised to Follow

Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has nationalised his country’s lithium reserves, declaring that “the lithium is ours” via a rushed law that both the Senate and Congress approved this week. Contracts for private lithium investment operations in the country will now “have to be reviewed,” López Obrador said. A major lithium project in the northern Mexican state of Sonora, which had been developed by the London-listed Bacanora Lithium but is now controlled by China’s Ganfeng Lithium following the latter’s successful takeover offer, faces an uncertain future. Just this month, Ganfeng had floated the idea of US automakers making a “strategic” investment in its Sonora project, including signing offtake agreements. Now, that seems unlikely.

Mexico’s move is likely to come with its own roadblocks: It remains to be seen whether Mexico will have the necessary capital and technical expertise to develop a profitable, nationalised lithium industry. However, the move is also indicative of a broader push for resource nationalization in the region. Chile recently took the first of several steps that could pave the way to nationalizing its copper and lithium mines. If the US were thinking strategically, this could be a ripe opportunity to re-claim Western hemisphere competitiveness in the critical mineral sector.

Don’t Call It a Comeback: Nuclear Energy Returns to the Limelight

As disruptions from the Russia-Ukraine crisis bring new attention to energy security, the world appears to be doing an about-face on nuclear energy. This month, South Korea reversed its nuclear phaseout plan. The UK government could approve up to eight more nuclear reactors under its new energy strategy after what the government calls “decades of underinvestment.” Belgium has resolved to leave open two reactors that had been set for closure. And Poland wants to build its first reactors. Meanwhile, the US just unveiled $6 billion in funding for nuclear plants to keep them from shuttering, and nuclear startups attracted record funding from venture investors last year. For its part, China has identified nuclear as a key area of energy-related development, and currently has by the far most reactor capacity under construction.

But nuclear is no silver bullet. As a response to energy security threats exposed by the Russia-Ukraine war, nuclear energy has a vulnerability of its own: dependence on Russia, the world’s largest exporter of enriched uranium. The US relies on Russia — and its allies Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — for 46% of the uranium needed for its nuclear power plants.

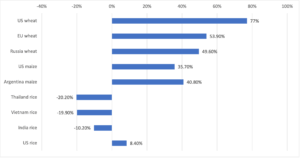

Global Fertilizer Shortage Injects More Uncertainty into Food Supply

Fertilizer costs are near double what they were a year ago: Russia is the world’s largest fertilizer exporter; disruptions from the war in Ukraine, and sanctions issued in response, have slashed those exports. Resultant, and likely enduring, fertilizer shortage threatens an already strained international food market – even in areas that are considered to be relatively sheltered from the dramatic inflationary disruptions of the Russia-Ukraine war. Take, for example, rice, not a major export of Russia or Ukraine. In March, while the prices of wheat and maize surged, most types of rice actually notched sizeable drops in prices. That may not hold true for much longer. Soaring fertilizer costs are catching up with rice farmers, who will be forced to cut back their use at the expense of lower yields. The International Rice Research Institute estimates yields could fall 10% next season, or by 36 million tons of rice. Peruvian rice farmers are already struggling as rising urea prices render rice farming unprofitable. There looks to be scant chance of a reprieve from global food inflation – and, with it, shortage.

(Photo by Pexels)