When the Tightrope Is Too Tight: HSBC West, HSBC East

The Financial Times reported this week that China’s top insurer, Ping An, the largest shareholder of HSBC, told the London-headquartered bank to split up into two separate operations: One Asian, one Western. The reasons Ping An cited were higher profitability, lower capital requirements, and more flexibility in decision-making. The likely, unspoken reason? Navigating the increasingly treacherous tensions between China and the west.

Calls for a breakup are not new. For years, HSBC has straddled—and some might say walked a tight rope—between east and west. But geopolitical complexities have intensified in recent years, particularly after HSBC provided information to US prosecutors leading to the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, as well as the bank’s decision to freeze the assets of exiled Hong Kong opposition politician Ted Hui. The big question here is whether HSBC is the canary in the coal mine. Should it indeed split into two, would that precipitate a trend of global bank breakups—and would this entail decoupling in the financial space, or complicated acrobatics that manage to avoid that (no need to walk a tight rope if you have positions on both sides)?

With Commodities Squeezed, So Is Traders’ Liquidity

Shortages of, and disruptions to, commodities is driving global energy and food inflation, and prompting concerns over longer-term social and industrial stability. But there’s also another effect: a massive liquidity crunch for commodity producers and trading firms. We’ve already caught a glimpse of this with the nickel short squeeze on the London Metal Exchange. That could be just the beginning. The risk now is that similarly chaotic squeezes will play out across a broader swathe of commodities.

Already, traders are scrambling to shore up their short-term cash supplies to cover hedging positions. European banks have stepped up lending to commodity trading firms. But what will happen if financial institutions decide to be less generous? Or if loans can’t be repaid? Of course, where there’s risk there’s also opportunity: this week, Invesco launched what’s believed to be the first commodity ETF linked to the energy transition, holding futures contracts for metals like cobalt, copper, nickel, and aluminum.

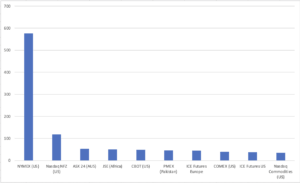

Top 10 exchanges by number of commodity futures and products (end-2021)

The EU Steps Up for Lithuania, Kind of

Last November, China imposed a raft of discriminatory trade restrictions on Lithuania for allowing Taiwan to open a de facto embassy in the capital. The restrictions went so far as to cut off not only all direct trade with Lithuania, but also all imports of products from other countries made with Lithuanian parts. Now, this week, the EU set up a €130 million scheme to support Lithuanian businesses affected by China’s measures. Under the EU scheme, affected Lithuanian companies can receive loans of up to €5 million, to be repaid within 24 months, for “sourcing of (new) inputs from different sources, looking for entering into new business markets or using the time to undertake such efforts.”

Admittedly, this is not a lot of money: Taiwan, whose economy is less than 1/20th that of the EU’s, in January extended a $1 billion credit fund to Lithuania, on top of another $200 investment fund. Still, the EU is sending an important message that it will stand up for its member states against coercion from China – or, at least, will do so on questions of free and fair trade.

Maximising de Minimis

A regulatory loophole means tens of billions of dollars of goods are entering the US free of tariffs and inspection. Under the de minimis rule, goods valued at $800 or under and shipped directly to the buyer can avoid tariffs. Customs data obtained by the Wall Street Journal show that the known value of de minimis imports was $67 billion in 2020, up from $40 million in 2012. Over 10% of Chinese imports by value now arrive in the US under the de minimis threshold. That means billions lost in tariff revenues. It also means large quantities of good that bypass customs inspection, making it easier for illegal items or goods made with forced labour to enter the US. One proposed way to close this loophole is to exclude goods from non-market economies like China’s from the de minimis option. That would deal a big blow to Chinese fast-fashion retailer Shein. Still, while closing the de minimis loophole could mean more tariff revenues and closer goods inspections – and could even help protect US e-commerce jobs – this is hardly the answer to the more fundamental US-China trade imbalance, and the non-market Chinese policies that propel it.

(Photo by Pexels)