MARKETS: Has Moscow Launched Decoupling? It’s Up to Washington

Over the past month, more than 400 US companies have announced that they will terminate, or scale back, their operations in Russia. These include icons of American soft power like McDonalds, legacy industrials like Boeing, and US tech champions like Apple. Their moves underline the power of the private sector in modern conflict, and statecraft in general – as well as the limited power of the government. Their moves are also being framed, albeit perhaps prematurely, as a threat to globalization: Are companies about to have to pick a side? With an increasingly sharp rift between the West-led global order and rising authoritarian challengers, will companies no longer be able play by the rules of all the different countries in which they operate – will they have to pick a side? This could be how decoupling happens. But whether it does hinges on two key questions, both of them up to the public sector, even if little else is:

- The biggest uncertainty lies in whether the US, its allies, and its partners stick to their (figurative) guns vis-à-vis Russia and China. If not, the private sector won’t either. If after hullabaloo dies down or attentions shift away, Washington and Brussels accept the status quo, companies will as well. Recent precedent, whether attempts to de-list Chinese companies or so-called red lines, suggest that international resolve is not to be taken for granted. But Russia’s invasion also shatters recent precedent.

- And then there is the matter of carrots; whether governments will re-think their approaches to their private sectors. Right now, US policy (e.g., anti-trust policy) is actively working to restrict corporate power – even as companies exert power on behalf of the US. This limits not just the resolve, but more important the ability of the private sector to step up. A more pro-industry domestic policy could be what the US private sector needs to take a long-term stand.

FACTORS: The US has no LNG to spare

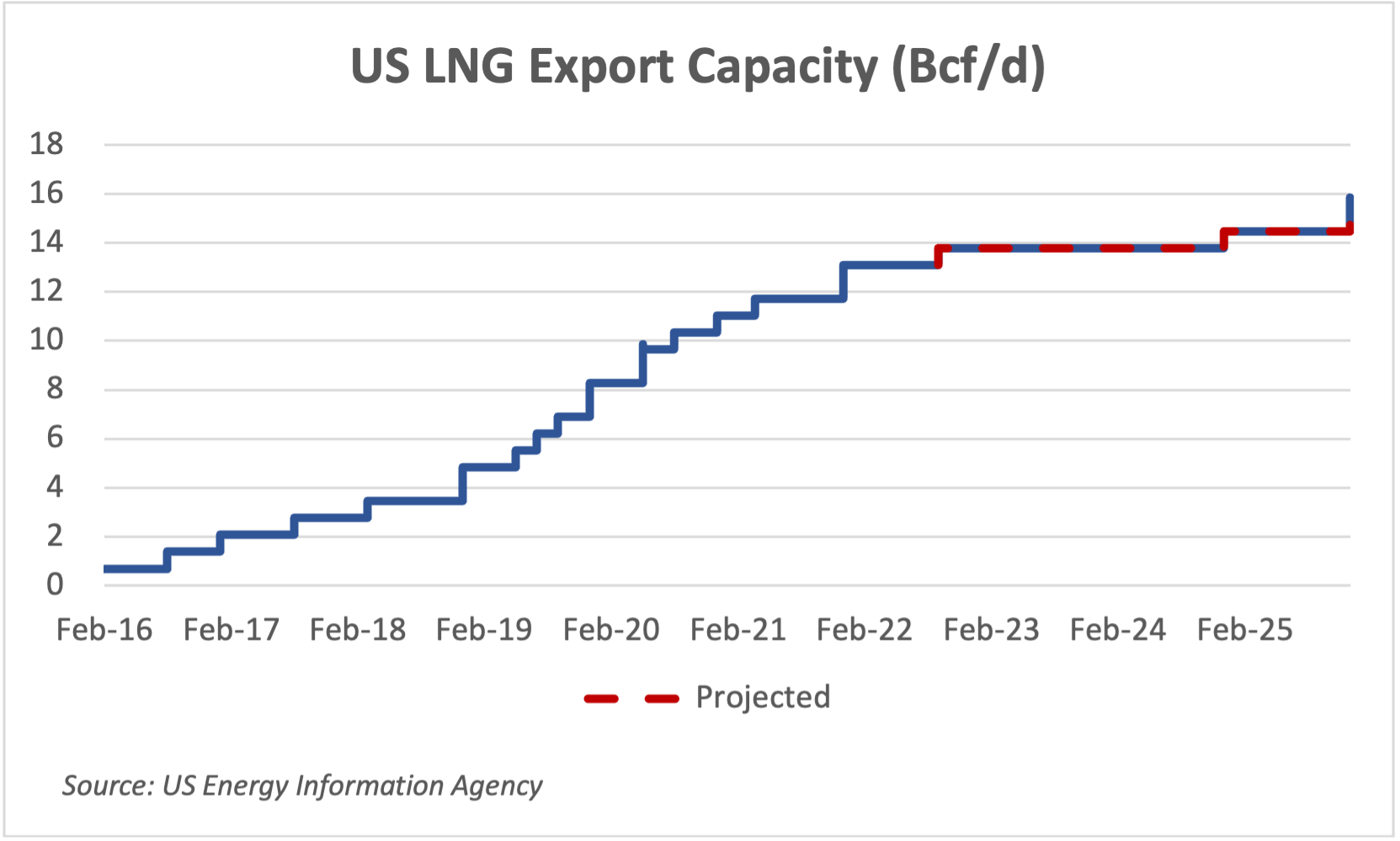

On March 25, the US and EU announced a new plan to increase US LNG exports to Europe by 15 billion cubic meters in 2022, and to triple those in subsequent years. The goal: To help Europe wean itself from Russian energy. The announcement is promising. But it leaves unanswered the question of how. US LNG export plants are already operating at capacity. They reached a record 13.3 bcf/d in February. That figure will rise to 13.9 bcf/d by the end of the year once a completed new terminal, Calcasieu Pass in Louisiana, becomes fully operational. But that’s still less than the additional 1.5 bcm per day the US would need to export in order to reach the 15 bcm target. Plus there are the questions of already overburdened global logistics systems and how they are expected to handle the additional exports – as well as how the US government expects to go about telling LNG producers who they are to sell to.

FACTORS: Preparing for a Metals Morass

On March 25, the London Metal Exchange (LME) announced that it will double its default fund, the pool of funds that it maintains to absorb the costs of a member’s non-performance, next month. The move responds to the heightened risk of member default as metal prices continue to skyrocket. This adjustment signals how major an effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and the international community’s response – is likely to have on metal supply, and every market and factor built on top of it. And while nickel has received much of the recent attention on the subject, it’s by no means the only potential pain point: Russia’s market share of total exports in nickel is estimated at 49 percent, palladium 52 percent, aluminum 26 percent, platinum 13 percent, steel 7 percent, and copper 4 percent. And let’s not forget that demand for many of these metals is poised to grow over the years ahead: For example, the International Aluminium Institute released a report on March 26 forecasting a 40 percent jump in aluminum demand by the end of the decade.

(Photo by Pexels)