Indonesia Adds to the Cooking Oil Squeeze

Amid global shortage of cooking oil caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil – Indonesia is adding to the squeeze. On April 22, Jakarta said that it was banning all exports of palm oil. Just days later, it abruptly expanded the ban to cover both refined and crude product. Indonesian exports of palm oil represent 52 percent of the global total. This sudden disruption will further drive up prices of the world’s most widely consumed cooking oil, as well as the many packaged foods and other products that contain it, at a time when global supply is already stretched thin.

Indonesia’s move is likely to be reverberate particularly intensely in India and China. India is the world’s largest importer of palm oil, which makes up 40% of its vegetable oil consumption. China is the world’s second largest importer of palm oil. Moreover, Beijing’s trade activity might further squeeze supply: Over recent moths, China has increased palm oil imports to account for reduced supplies of other vegetable oils due to the Russia-Ukraine war.

More broadly, Indonesia’s move is an early example of food and resource nationalism that is poised to increase with global shortages – and that compounds the consequences of those shortages. Jakarta’s export ban appears to aimed at cushioning the effect of rising domestic food prices, at the expense of reduced export earnings (palm oil is Indonesia’s second-highest earning export product after mineral fuels, representing over 10% of export revenue); the Indonesian rupiah dropped to an eight-month low after ban was announced, which will make imports more expensive.

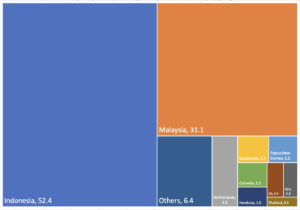

Top exporters of palm oil by percentage share of trade value (2020)

Russia Needs Lithium

Russia risks running short of lithium after its main suppliers, Chile and Argentina, halted exports due to Western sanctions on Moscow. Should Bolivia follow suit, Russia would be effectively left out to dry: Its lithium-ion battery production is currently fully reliant on imported feedstock. Without lithium imports, Russia would be hard-pressed to produce lithium batteries, which are used not only in EVs and power grids but also in military equipment like submarines. In response to the export bans, Russia’s state-owned nuclear power supplier Rosatom and metals producer Nornickel said this week that they plan to develop the Kolmozerskoye lithium deposit in the country’s northwest.

Over recent years, Rosatom has decided to prioritize sourcing lithium from abroad for processing domestically. Now, that looks to be a decided strategic mistake. But Russia is not the only player vulnerable to this sort of upstream resource squeeze: The US relies on imports for a huge share of its critical material inputs, including lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals. And Beijing plays a huge role in those value chains. Right now, it’s Russia in the hot seat. But what happens if China decides to turn the screws?

…and the West needs lithium too

And recent updates from Tesla underscore the extent of this vulnerability. At its earnings call last week, Tesla divulged a piece of data that it had previously kept closely guarded: “nearly half” of all Tesla vehicles produced in Q1 had a lithium-ion phosphate (LFP) battery. This signals a decisive shift away from nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) cells. LFPs are cheaper than NCMs, though they are also bigger, heavier, less energy-dense than the NCMs that have so far dominated in the West (LFPs currently make up only 3% of EV batteries in the US and Canada, compared to 44% in China).

LFPs also come with a major dependence issue: China currently commands 90% of global LFP capacity. Moreover, LFPs use more lithium than NCMs; a shift toward LFPs will only exacerbate projected lithium shortages. The potential good news: As of this week, all patents protecting LFP technology in the West have expired. Start ups can now make LFPs without patent restrictions. That said, none is likely to reach commercial scale anytime soon.

When Divestment from Russia Paves the Way for China

Chinese energy giants China National Offshore Oil Corp (CNOOC), China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) and China Petrochemical Corp (Sinopec) are reportedly in early stage talks with Shell to acquire the UK-headquartered firm’s 27.5% stake in the Russian Sakhalin-2 LNG project. The remaining stakes in the Sakhalin-2 project are held by Gazprom (50%), Mitsui (12.5%), and Mitsubishi (10%).

Should these talks bear fruit, a China-Russia alliance would own nearly 80% of the project. That is causing worries in Japan, which relies on Sakhalin-2 for the bulk of its Russian LNG imports and around 8% of its total LNG supplies. The Japanese prime minister says divesting from Sakhalin-2 is not an option. Japan is used to getting creative to secure its energy supplies. But now it does so in an environment of unprecedented geopolitical tension and competition for factors.

(Photo by Pexels)