THE BIG DEALS

A week of breakthrough legislative action shows that legislation is not enough

This week has seen a rare stretch of apparent movement in Washington. Thanks to an abrupt U-turn by Joe Manchin, Biden’s centerpiece domestic policy plan seems poised for a revival: The West Virginia senator agreed to a sweeping 700 billion USD climate, energy, and tax package – originally known as Build Back Better and now conveniently rebranded as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The surprise deal comes not even two weeks after Manchin appeared to have all but scuttled the bill. Now, it needs unanimous Democratic support, including that of Arizona’s wildcard Krysten Sinema, to pass the Senate next week. Then it heads to the House, where it will face stiff GOP opposition. But even with those remaining hurdles, the outlook is largely positive.

Meanwhile, the Chips and Science Act – which includes 52 billion USD in subsidies for domestic semiconductor production – cleared both the Senate and House this week and is now headed to President Biden’s desk. Democrats are cautiously celebrating the results of their long-game approach of patient negotiations. So are new energy and semiconductor companies, as well as their related ecosystems.

But don’t forget that while these bills are being branded as game-changing breakthroughs, they are the tip of the iceberg in terms of the industrial investment that the US needs. They are also limited in both their scope and the guardrails on investment they propose. (Take, for example, the reality that the companies poised most to benefit from the CHIPS Act also have production and research facilities in China). This inadequacy is a feature not a bug of the US legislative process; an important reminder that government action can spur, but not fulfill, the industrial investment the US needs. In a best-case scenario, CHIPS and the Inflation Reduction Act should be the signals that encourage a new wave of private-sector investment in critical industry chains, with the government imposing costs for doing it wrong and incentives, including shouldering risks, for doing it right – but not trying to keep its hands on the wheel.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSRecession or not, things don’t look pretty

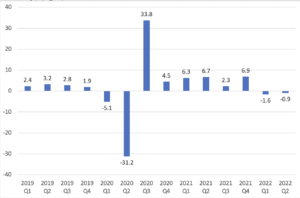

Is the US in a recession or is it not? Numbers released on Thursday show that GDP shrank for a second straight quarter, notching a 0.9 percent annualized fall in Q2 following Q1’s contraction of 1.6 percent at an annual rate. The widely accepted technical definition of recession is two consecutive quarters of economic contraction, which puts the US squarely there.

But no Administration wants the R-word looming over them; the Biden Administration is pushing back by citing the strength of the current job market, consumer spending, and household balance sheets. Semantics aside, other details from the GDP report point to a downturn, too – and likely matter more than whatever word is being used to describe today’s economic challenge. Business construction (e.g., of factories, warehouses), fell by 11.7 percent, particularly concerning in that it signals waning investment in already inadequate US production facilities. Home construction dropped by 14 percent under the pressure of rising interest rates. Government spending has also slowed. And while consumer spending is currently the main engine for the US economy (not a great sign in an era where demand outstrips supply), consumers are tightening their purse strings, too as prices and stress levels rise: Spending only grew by 1 percent, far less than preceding quarters. In short, momentum is sputtering and confidence is down, whether the recession label sticks or not.

And the US is not alone. Recession also looms over Europe, spurred by a region-wide energy crisis, with it skyrocketing inflation, and political and economic troubles in Italy that could have ripple effects – even splintering ripple effects – around the bloc. The global outlook is similarly gloomy. The IMF has slashed this year’s growth outlook and warned that the world “may soon be teetering on the edge of a global recession.”

Rally, rally, rally?

If recession fears are weighing on the economy, stock markets are proving surprisingly bullish. The S&P 500 just posted its biggest monthly gain since November 2020, when the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines pumped optimism. The Dow Industrial and Nasdaq Composite were up strongly, too. Cryptocurrencies also surged this month, with S&P’s crypto megacap index – which tracks bitcoin and Ethereum – up 37.4 percent in July. The rally seems to be a function of economic contraction itself, which likely means an end to the Fed’s rate hikes. But contraction is hardly a long-term positive and at a certain point, economic fundamentals matter more that monetary policy. As Amazon, for example, cautioned even while reporting strong earnings: “We are cognizant that things can change quickly.”

Big oil reports bumper earnings

It has been a great quarter for oil majors as energy prices have soared. The three largest Western oil companies Exxon, Chevron, and Shell all posted record profits for the second quarter. So did France’s TotalEnergies. BP will likely report record earnings next week, too. These firms are largely boosting returns by repurchasing shares and hiking dividends. The big question is how many new investments they intend to make in new production, whether of conventional or renewable energy. But regardless, energy prices don’t seem likely to come down anytime soon, so another quarter of bumper profits could line the supermajors’ wallets for more potential mergers, acquisitions, and new projects.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSRussia continues to turn the screws on natural gas markets

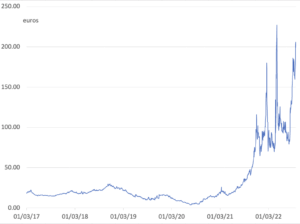

Russia resumed flows of natural gas through the Nord Stream pipeline at reduced levels last week, providing a modicum of relief for Europe after fears of a total shutdown. But – unsurprisingly – Russia’s Gazprom has since reduced supplies again, halving gas deliveries to 20 percent of capacity on Wednesday.

Once more, the cited reason is turbine maintenance. Once more, this seems to be Russia weaponizing the West’s dependence on its resources. In addition to further squeezing Europe, this latest move is increasing competition in the broader, already red-hot global LNG market. Price-sensitive countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh are at risk of further power outages. And we can expect more knock-on effects from energy shortage ahead. For example, Germany’s chemicals giant BASF said this week that it is slashing ammonia production due to the natural gas crunch. That will crimp fertilizer production, in turn putting pressure on food prices.

Dutch TTF Gas Futures Prices, euros per megawatt hour

Source: FactSet

Will Ukrainian grain make it through the Black Sea?

Speaking of food prices: Last Saturday, Russia and Ukraine signed a deal, brokered by the United Nations and Turkey, to allow grain exports through the Black Sea, intended to help address the global food crisis. Grain prices momentarily dipped on the news; the world breathed a sigh of relief. But just hours later, a Russian missile strike on the port of Odessa, the very port needed to export Ukrainian grain. Still, matters seem to be moving forward on the agreement: This week, Turkey set up a control center to monitor grain exports and expects the first shipment to leave Black Sea ports as early as this week.

Remember, though: Just as it is with natural gas and Europe, Russia is likely to continue to signal – clearly and with potentially devastating effects – that it calls the shots when it comes to Ukraine’s ability to export grain. And regardless, while this deal could be a critical move for food supply, it is no panacea: Extreme weather events, rising energy costs, and various export bans continue to drive up world food prices, and did so even before Russia’s invasion.

A new policy tool for refilling the SPR

On July 26, the Biden Administration announced yet another release from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve – on top of a record 125 million barrels already sold into the market. At the same time, the White House also announced a new set of policy tools that will govern its SPR buyback plan, set to begin after Fiscal Year 2023, intended not just to help replenish the SPR but also to spur production: Fixed-price forward contracts. These mean the DoE can set a price today at which it will buy oil from producers tomorrow to refill the SPR – rather than simply buying tomorrow at tomorrow’s price, as with conventional contracts. This mechanism is supposed to incentivize production, as it protects producers from price drops at the time of delivery. In other words, the risk of an oil price crash is borne by the government, not producers.

A technical breakthrough could ease scandium’s scarcity

The US lists scandium as a critical mineral. Used in scandium-aluminum alloys, the metal dramatically improves aluminum’s strength, flexibility, heat resistance, and weight, making it ideal for aircraft and aerospace applications. Much of global scandium production is in China, however. Russia also produces the metal, but the war has disrupted supplies. That leaves the US highly dependent on imports from unreliable partners (read: geopolitical adversaries). A recent innovation from Rio Tinto could change that: the Anglo-Australian mining giant has figured out how to extract scandium oxide from its existing titanium operations, making it the first North American producer of the mineral. The company has also just begun extracting another critical mineral, tellurium, from its copper operation in Utah. As Andy Home at Reuters puts it, “Mine and processing waste is fast emerging as a new frontier for critical metals supply.”

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSRussia announces plans to withdraw from the International Space Station

Russia announced Tuesday that it will pull out of the International Space Station by 2024, and instead build its own orbiting outpost. The International Space Station is run jointly by Russia, the US, Europe, Japan, and Canada. It conducts scientific research and technology testing. Should Moscow be serious about its threat, Russian withdrawal would put major pressure on the space station, making it a tremendous challenge for the 24-year-old project to stay running – especially if, for example, it became necessary to remove all Russian components. Of course, Moscow’s announcement could also be bluster; an effort further to impose pressure on the West. As former Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield tweeted in reaction to the move, “Remember that Russia’s best game is chess.”

Still, even just as a threat, Moscow’s announcement underscores the degree to which assumptions about a post-Cold War interconnected world are faltering. The past decades have seen extensive and growing international cooperation between geopolitical adversaries, or at least competitors, especially in science. Now, it seems increasingly likely that that was a blip not a trend.

Will a tritium shortage trip up nuclear fusion?

Nuclear fusion offers the promise of abundant clean energy. But it is still very much at an experimental stage. Technical hurdles abound. So do resource challenges: There might not be enough tritium in the world to fuel fusion reactors. But recently, fusion scientists have been working on how to combine tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen, with its sibling deuterium. The world has an abundant supply of the latter, but scant supplies of the former. Could more tritium be produced? Possibly. Nineteen Canada Deuterium Uranium (CANDU) nuclear reactors are responsible for the entire global commercial supply of tritium. Other countries have CANDUs, too, including four in South Korea, two in Romania, and two in China. Could these countries eventually become key suppliers of fuel for fusion energy?

(Photo by Pexels)