MARKETS: The Chinese market fake-out

This week began with Chinese stock markets plummeting. On March 13, JP Morgan downgraded 28 major Chinese internet stocks – including heavy hitters like Alibaba, Tencent Holdings and Meituan — to “uninvestable,” threatened by regulatory, geopolitical, and macro risks. The move, and larger sell-off of which it was a part, responded to concerns stemming from US-China conflict, COVID-19-induced lockdowns across China, a weakening RMB, and secondary sanctions that might result from China’s “pro-Russia neutrality.” As markets fell, commentators in the US warned that this was a true moment of reckoning for the Chinese financial system — even a 2008 redux. Still now, commentary continues to interpret the events of last week as a sign of systemic weakness in China’s markets and a bellwether for financial decoupling. But that commentary misses the real the story: Within days of the crash, the Chinese government stepped in, promising support for real estate and technology companies. Stocks rebounded, at pace. Here are the lessons we should be learning from events of this week:

- If a lot was made of the rout in Chinese markets on March 13, more should be made of Beijing’s willingness to intervene, and the upswing that resulted. Chinese markets asymmetrically benefit from the government’s desire for them to succeed – and Beijing benefits from the international financial sector’s willingness to accept the Party line.

- While Chinese tech companies are certainly exposed to a host of risks, so is everyone: US tech companies, for example, face enormous supply chain challenges aggravated by a dearth of domestic manufacturing and that make them just as susceptible to Chinese lockdowns as PRC companies are (see: Apple). And US tech companies also face risk from US and European regulatory measures that are far more aggressive than Chinese equivalents vice the PRC’s domestic champions.

- So is the recent volatility in the Chinese market necessarily an omen of fundamental weakness and financial decoupling? We say no. But could it be? Yes – if, that is, the US government and private sector seize on it to reduce dependence on China. Now would be an opportune moment for divestment, as well as for the US government to follow through on measures that incentivize as much (e.g., delisting). The big question: Will short term volatility open the door to long-term positioning?

FACTORS: Let them eat cake

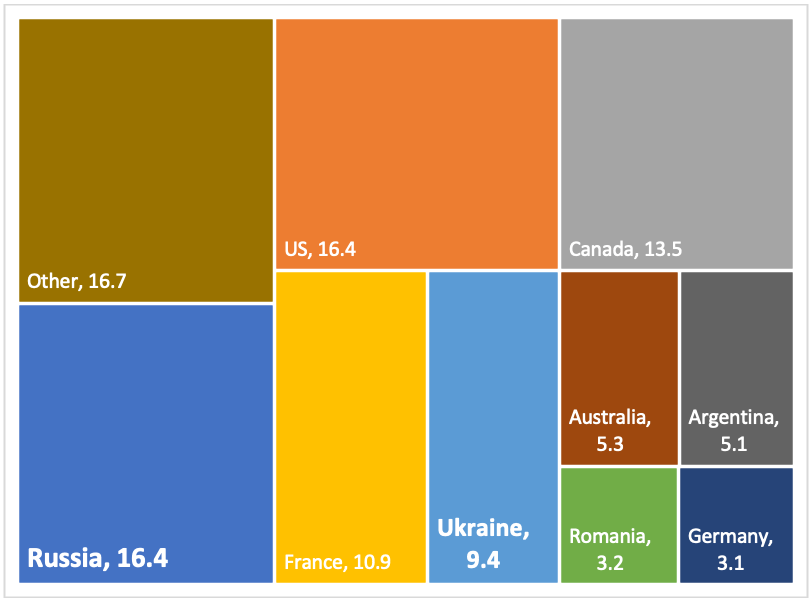

Ukraine and Russia are two of the world’s biggest grain exporters. In 2019, they, together made up 26% and 20% of global wheat and barley exports, respectively. Now, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means that not only are the two countries under threat, but so is shipping to and from. This severely threatens supply in an already vulnerable value chain, still reeling from pandemic- and climate-related disruptions. The direct consequences are clear: Food prices are likely to soar over the coming months and year, at least, and global hunger with them. And/but this first order threat could mean a ripple of second order ones, including ones that could shape the geopolitical landscape:

Top global wheat and meslin exporters (2019)

- Food shortages risk creating political instability in existing hotspots like the Middle East and North Africa. Those regions disproportionately depend on the now-hamstrung Black Sea shipping route and have close economic ties with Russia and Ukraine (e.g., Egypt gets 70% of its wheat and meslin from Russia and Ukraine). This could put us on the verge of a new Arab Spring. And should that be the case, the US will be hard-pressed to respond in a way that does not detract from the competition with Russia and China that itself created this mess.

- China is actively competing for the world’s increasingly limited agricultural inputs. Over the past weeks, China has responded to the threat of global food shortage by accelerating purchases of US food products. As food becomes a strategic resource, will the US let that continue? Will it divert supplies to Europe (and if not, can US-EU relations hold up)? Will agriculture take over from telecommunications as the battlefield of US-China competition?

FACTORS: Are Europe’s Rare Earth Efforts Headed Back to Square One?

During its March 10 earnings call, Neo Performance Materials — a Canadian publicly-listed advanced materials company and key part of the incipient Europe-North America rare earth supply chain — disclosed a critical dependence on Russia: Neo’s rare earth separation facility in Silmet, Estonia, sources 70% of its rare earth material feedstock from Solikamsk Magnesium Works in Russia. The other 30% comes from Energy Fuels, a US-based company. Neo’s Estonia plant is Europe’s only commercial rare earth separation facility. And, while Solikamsk has not yet officially been sanctioned, Neo is actively preparing for that possibility. It reports being in talks with “half a dozen emerging producers” worldwide in an attempt to diversify its raw material supplies. But options are limited. China is out of the question: As Neo CEO Constantine Karayannopoulos explained, “China is not an option [as a supplier of feedstock] because it’s not allowed to export unseparated rare earth streams from China.” And Energy Fuels, a US-based company, does not have enough access to monazite, a critical input into feed material, to increase supplies. Without any alternative source of feedstock, Neo’s Silmet project will be out of luck. Its European buyers of downstream rare earth products will likely have to turn to China. That would set back Europe’s efforts to reduce reliance on China.

The bottom line: This is yet another example of why investments in supply chains should span the value chain — and start at the beginning. Mid- and downstream positioning means very little without upstream capacity to back it up.

MARKETS: US and UK reach steel and aluminum deal, pushing back against China’s global resource outposts

The US and UK agreed on March 22 to roll back Trump-era tariffs on British steel and aluminium. Under the deal, the US will allow 500,000 tons of steel “melted and poured” in the UK to be imported duty-free — with higher volumes subject to a 25 percent tariff. A 10 percent levy will apply to aluminium imports of up to 21,600 tons annually. These terms are not a surprise; they largely mirror the agreement formed between the US and EU last year. But one additional provision of the deal is notable: The requirement that the UK audit the financial records of all Chinese-owned British steel firms — and share the results with the US in order to assess Chinese government “influence” and confirm that the producer in question would not “materially contribute to non-market excess capacity of steel.” This is a direct reference to Chinese steelmaker Jingye Group’s 2020 acquisition of the British and Dutch assets of British Steel, a move through which Jingye sought to expand its technological capacity, international market presence, and access to downstream European nodes.

This clause echoes a provision in the US-EU deal that barred the transshipment through the EU and into the US of steel or aluminum products produced in China. Together, both agreements suggest that the US, EU, and UK are re-thinking their frameworks for international trade and international trade remedies to combat not just non-market players in China, but also their global outposts – and Beijing’s larger state-backed efforts to invest in resource production overseas. This is a good sign: The US, EU, and UK are coordinating, if with baby steps, to counter the Beijing’s economic distortions, and in a way that recognizes both the indirect and the international nature of China’s offensive.

(Photo by Pexels)