War, Weather, and Waste Threaten the Global Wheat Market

The one-two punch of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and poor weather continues to strain the global agriculture market, and with it tomorrow’s food supply. Two weeks ago was fertilizer; last week cooking oil. Now, wheat is in question – a victim of war, weather, and waste.

Russia and Ukraine are the world’s largest wheat exporters. That’s one strike. Strike two: Droughts, floodings, and heatwaves are undermining harvests elsewhere around the world, with analysts predicting that global output will drop in the 2022-2023 year for the first time in four seasons. And the third, wildcard strike: Viral videos of ruined wheat fields in China have sparked concerns that farmers are cutting down crops prematurely for sale as silage for animal field, threatening both their harvest sand China’s food supply. Beijing appears to be taking the matter seriously. The Chinese agricultural ministry has launched an investigation into suspected destruction of wheat crops. One farmer in Henan province expressed surprise: cutting premature wheat to sell as silage has always been done in the past, but has never sparked such outrage. This suggests particular concern from Beijing over the country’s food security. And such concern is likely to lead China to stockpile foodstuffs – including from international markets – which in turn is likely further to strain international supply.

Chicago Board of Trade Wheat Futures

Source: CBOT

Baby Formula Shortage Wreaks Havoc in the US

Agricultural commodities aren’t the only victim of recent supply chain chaos – and geopolitical tension not the only perpetrator. The US is facing a nationwide baby formula shortage that has left families unable to feed their children: 43 percent of baby formula is out of stock nationwide. The shortage is a function both of general supply chain snarls and a large-scale recall. With baby formula already in low supply thanks to pandemic-induced disruptions, the FDA detected a potentially deadly germ on site (although not in the products of) an Abbott Laboratories factory in Sturgis, Michigan. Abbott, which produces about 40 percent of the country’s baby formula, issued a recall and stopped production. And while the plant could be up and running within two weeks, it will take some six to eight more for the resultant formula to appear in stores.

This is the stuff that revolutions are made of: The shortage, which is expected to last through the rest of the year, affects families’ fundamental survival. It disproportionately affects the lower income population. And Washington is far to the right of the problem. On the defensive, the FDA reports that it is working with major manufacturers to increase their production as well as to streamline imports of formula from elsewhere; a House committee has scheduled a hearing on the subject for May 25. Needless to say, those efforts are quite little quite late. This lackluster response underlines the reality that the US continues not to recognize quite how fragile supply chains are – or how critical it is to get ahead of them: When a key facility of a key producer shuts down after an FDA investigation, the government should recognize, and work to mitigate, consequences.

In Tungsten, a Promising Model for Public Private Partnership

Elsewhere, the market may be stepping up to resolve the omnipresent story of supply shortages – and dependencies. Take, for example, critical minerals and Tungsten in particular. Tungsten is considered a critical mineral by the US, EU, and UK. The metal is used in heavy industries like oil drilling and mining, as well as strategic sectors like electronics, defense, aeronautics, and automotives.

And thanks to decades of state support for the strategic minerals industry, China controls global tungsten production, with a 83.5 percent market share. And, a new, recent wrinkle: Russia is the world’s third-largest producer of tungsten, contributing approximately 3 percent of global supply. This constitutes a dangerous reliance on authoritarian countries for a critical mineral. But tungsten is also a rare case of promising investments that could help mitigate that reliance. Canada-listed Almonty Industries is working to reopen a tungsten mine in South Korea that was shut three decades ago thanks to low (State-supported) prices coming out of China. Almonty, which will receive funding from Seoul, reckons that once operational, it will be able to provide 10 percent of global supply. For now, it has a long-term offtake agreement with the Pennsylvania-based US military supplier and minority shareholder Global Tungsten & Powders. If this works, it should be hailed as a model for public private partnership in a strategic sector. And it should be replicated across the larger set of critical factors.

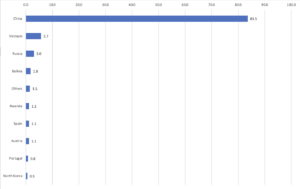

Percentage Share of Global Tungsten Production by Country, 2020

Source: USGS

When the World’s Aluminum Vacuum Is China’s Opportunity

At the same time, the challenge of China’s resource control may also be growing. For the first time since November 2019, China has become a net exporter of primary aluminum. In large part that’s due to soaring prices in Europe as disruptions to Russian supplies cause shortages of the metal. War-inflated European power prices have also forced aluminum manufacturers on the continent to curb production, presenting a lucrative arbitrage opportunity for Chinese sellers. Exports of Chinese semi-manufactured aluminum products (semis) will likely increase too, especially since Chinese sellers enjoy export tax rebates on semis but not unwrought metal. Foreign countries’ concerns over China’s dumping of aluminum, as well as risks of forced labor in China’s industry, might take a back seat as the world scrambles for supplies of the metal, a key input into everything from automobiles to kitchen utensils.

Europe Eyes the Upstream of the EV Industry Chain

There’s a critical missing link in Europe’s EV supply chain: the lack of a commercial refining facility. That could change if Green Lithium succeeds in building and bringing online its planned UK refinery. The Singapore-based commodity multinational Trafigura signed a deal this week to supply Green Lithium with lithium feedstock. The refinery, which Green Lithium hopes will be operational by 2024, is expected to have a capacity of 50,000 metric tons per year. That would represent 20 percent of the 250,000 metric tons of lithium Europe is projected to demand by 2025, according to Benchmark Minerals estimates. It’s not nearly enough to replace Chinese processing capacity, which currently makes up 58 percent of global lithium processing. But it represents much-needed investment in the upstream segments of the EV supply chain.