Welcome to a/symmetric, our weekly newsletter. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric.

This week:

- How Apple boosted China’s manufacturing base. The iPhone maker has long relied on Chinese suppliers, in turn helping them upgrade their technological capabilities. Now those suppliers are helping domestic brands like Huawei and Xiaomi chip away at Apple’s market share.

- Weekly Links Round-Up: EU defense industrial strategy, modems in Chinese-made port cranes, AI industrial applications, and US biopharma competitiveness.

How Apple boosted China’s manufacturing base

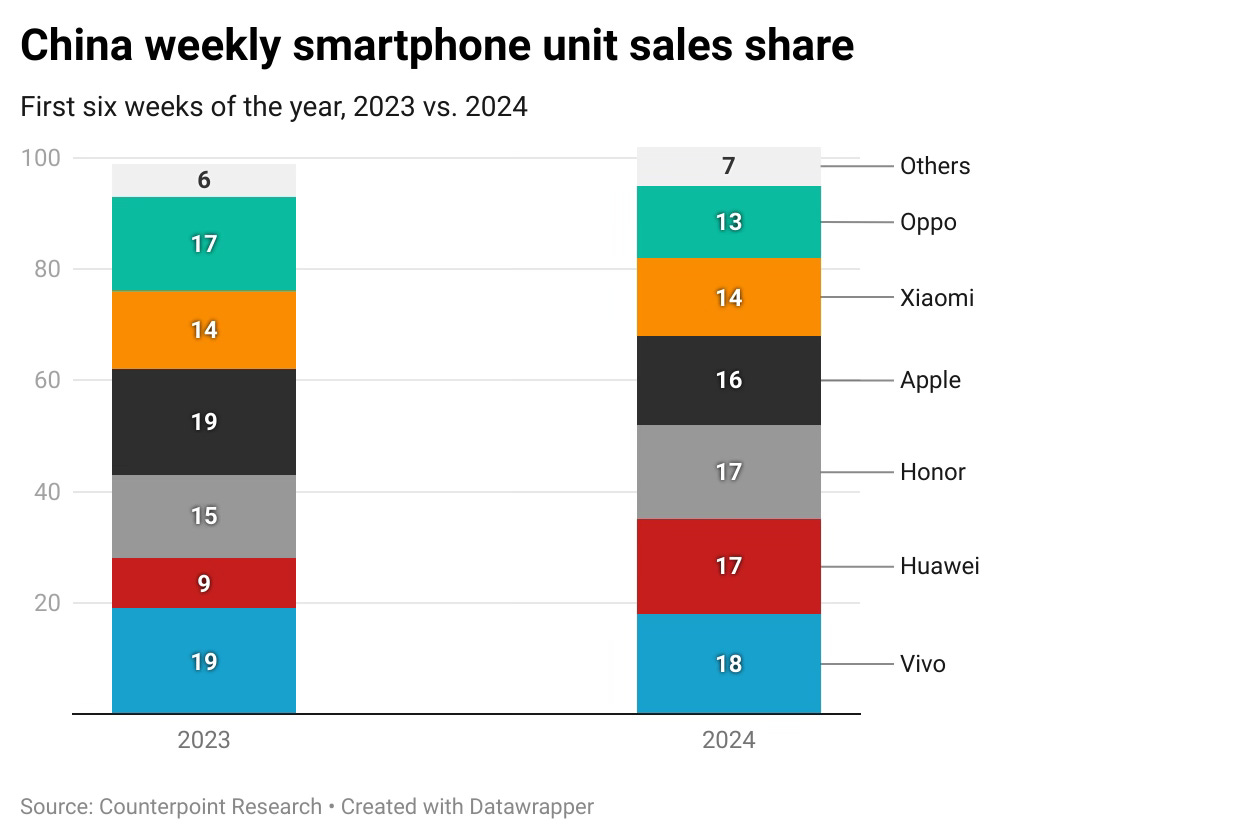

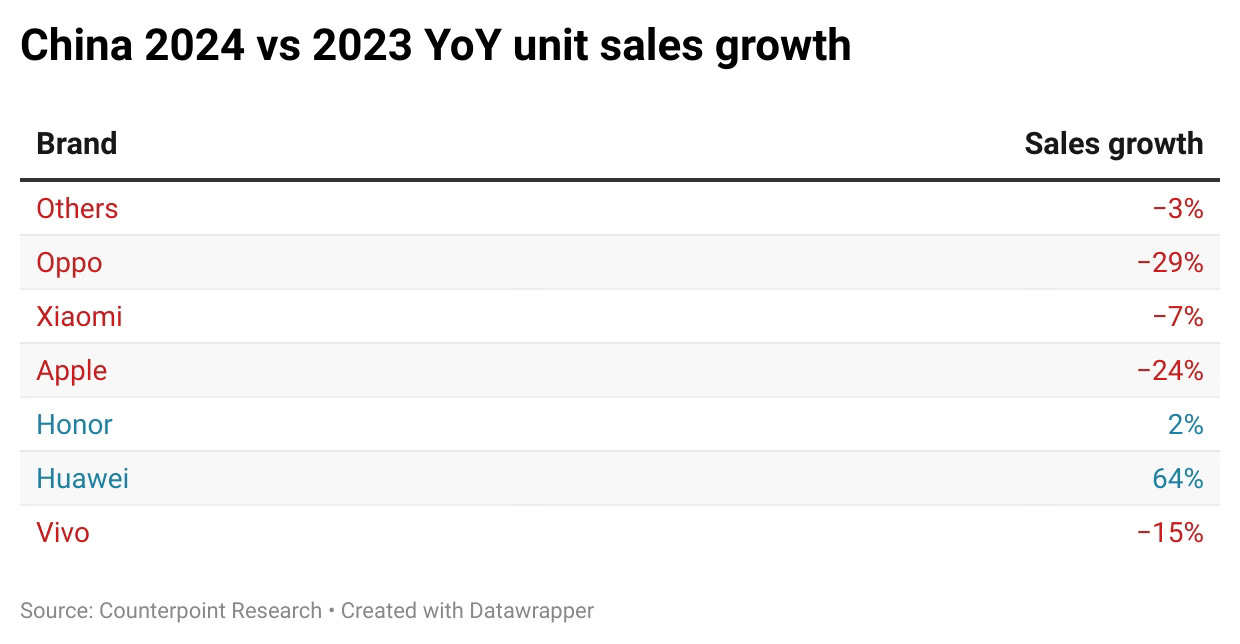

Bad news for Apple: iPhone sales in China plunged 24% year-on-year in the first six weeks of the year. And it’s not the only American firm dependent on Chinese manufacturing that’s suffering as local competitors make gains. Tesla’s February China sales fell to their lowest in more than a year.

Both Apple and Tesla have long tied their fortunes to China, relying on the country’s vast network of suppliers to manufacture their products at scale. China was happy to oblige. It saw the two US tech giants as “catfish” that would spur local companies to innovate—and eventually outshine foreign competitors.

China “should thank Apple,” says author and supply chain expert Lin Xueping. “It has actually made a huge contribution in China.”

In fact, Apple has also helped its Chinese suppliers grow their international presence. Suzhou-based Bozhon Precision Industry, Apple’s longtime provider of automation equipment, explicitly acknowledges that it is piggybacking off Apple’s global footprint to expand overseas.

The question now is whether Chinese competitors will leapfrog the likes of Apple and Tesla and leave them languishing in the dust.

Creating manufacturing superstars in China

Apple has helped create “many…manufacturing superstars” in China, writes Lin in his book Supply Chain Attack and Defense (we have cited his work in two previous posts, on ballpoint pens and solar panels).

One such star is Beijing Jingdiao. According to Lin, Apple plucked the machine tool maker from relative obscurity and helped develop it into a leading industry player:

“Beijing Jingdiao, once engaged in acrylic plate cutting, was not even recognized by the machine tool industry. However, Apple discovered the value of Jingdiao, making it the star of Apple’s mobile phone surface processing. Jingdiao replaced the expensive Japanese [machine tool maker] Fanuc, becoming the king of [computers, communications, and consumer electronics] processing in one fell swoop. With every iteration of Apple’s mobile phones, Jingdiao became ever more courageous. Apple has created many such manufacturing stars.”

A machine tool renaissance

Another example Lin cites is Apple’s decision to forgo the injection molding process (used to make the plastic mobile phones of yesteryear) in favor of using high precision, high speed machine tools to make iPhones.

Apple spurred demand for machine tools in two main ways, according to the Economic Herald. One was Steve Jobs’ insistence that the first-generation iPhone use glass screens, rather than easily scratched plastic ones. This required Beijing Jingdiao to come up with a new processing method to cut the glass. Another was Apple’s move to ditch injection molded plastic frames from the iPhone 4 onwards. This meant huge demand for machine tools.

“This was a blessing for enterprises with high-precision CNC machine tool technical capabilities,” writes the Economic Herald. These newly developed capabilities of Chinese machine tool firms would later prove highly transferable to “a large number of new applications with technical significance, such as semiconductors, medical precision equipment and other fields.”

Source: Huajin Securities, p.13 (translations added)

Lin notes that because thousands of machine tools were needed to mass produce iPhone frames, expensive machine tools from Japan, Germany, and Switzerland wouldn’t do. Foxconn, the Taiwanese contract manufacturer derives the bulk of its revenue from China, decided give it a shot.

In Lin’s telling, Foxconn teamed up with Japan’s Fanuc to adapt machining technology typically used for the aerospace sector, and tweaked it for making iPhones. Then Foxconn went scouring for machining tools—to the tune of two million a year. Leading Japanese suppliers like Toshiba and Sumitomo balked; that kind of volume was unheard of. So Foxconn decided to develop its own machining tools, and over time cultivated a crop of Chinese suppliers to manufacture them.

Reusing the iPhone supply chain to beat Apple

To summarize: Apple designed a product that pushed the limits of manufacturing, and in attempting to meet that challenge, manufacturers like Beijing Jingdao and Foxconn simultaneously drove the development of a network of materials suppliers and components makers in China.

“Apple, with its own strength and using the power of a single company, has promoted the upgrading of consumer electronics manufacturing capabilities,” Lin writes. “Apple has cultivated China’s electronic manufacturing capabilities, and Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo and others can reuse Apple’s mature supply chain.”

Now, as Apple faces declining sales in China, it will find that its local competitors are supported by a formidable group of homegrown suppliers that have played key roles in the “fruit chain” (as Apple’s supply chain is dubbed). That suits China just fine: domestic brands will be positioned to win greater market share, while domestic suppliers get to reduce reliance on Apple.

Weekly Links Round-Up

️ The EU unveiled its first ever defense industrial strategy. The document makes clear that production is power: Europe’s defense industrial sector needs to evolve to enable it to “mass produce a large set of defence equipment” in times of war. Brussels is investing €1.5 billion ($1.6 billion) on the effort between 2025-2027—a start, but not quite enough to shape the market or bring about a paradigm shift. (European Commission, European Council on Foreign Relations )

️ Suspicious modems in Chinese-made port cranes. A congressional probe of cranes at US ports “found communications equipment that doesn’t appear to support normal operations,” Dustin Volz reports. For a refresher, see our writeup on Chinese crane champions from last month. (WSJ)

️ AI needs industrial applications. So argues Shao Chunbao, a researcher at Peking University’s Center for Strategic Studies: “Artificial intelligence is valuable only if it becomes an industry. In this regard, China also has a comparative advantage.” We made a similar point in an earlier post analyzing China’s game plan for the AI race. (Guangming Daily)

️ The fight to maintain US biopharma competitiveness. “The United States has a long history of initially leading in advanced industries, only to subsequently lose its competitive advantage to other countries with more effective industrial policies and more patient private sector capital,” writes Sandra Barbosu. Can its biopharma sector avoid the same industrial decline that has afflicted telecommunications, solar, semiconductors, and chemicals? (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation)

️ Different flavours of de-risking. Francesca Ghiretti writes that China has been de-risking for decades (and we couldn’t agree more). She highlights a pertinent asymmetry: The EU “seeks to de-risk only where necessary and leave as much openness as possible…China, on the other hand, follows the opposite logic: de-risk wherever you can and rely on globalization where you must.” And who might expect to be more adept at exploiting that asymmetry? (MERICS)

(Photo by Torsten Dettlaff/Pexels)