Welcome to a/symmetric, our new newsletter. Once a week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric. You can also find us on Substack.

In this week’s dispatch:

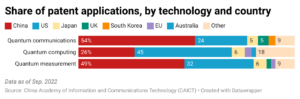

- A look at the global race to develop quantum technology, and how China is adopting an asymmetric strategy in pursuit of quantum dominance

- Weekly Links Round-Up

IBM’s new quantum chip, China’s quantum ambitions

IBM this week unveiled a new quantum computing chip and machine. Dubbed Quantum System Two, the computer connects super-cooled ‘Heron’ chips in a new way to significantly reduce error rates. It’s a key step towards IBM’s 2033 goal to produce truly functional quantum computers with thousands of qubits—the basic units of quantum information, and the quantum version of classical binary bits—up from the hundreds now.

“We’ve entered a new era of quantum computing,” says Jay Gambetta, VP of IBM Quantum.

That era is also a hyper-competitive one. Quantum technology is seen as a key battleground between companies and countries. The stakes are high: quantum computing holds out the promise of transforming critical sectors like aerospace, biotech, logistics, and materials —with implications for economic and national security. The US, EU, Japan, China, and others have all launched high-level quantum strategies.

The quantum competition is an asymmetric competition

For China, there’s an added incentive: shaping the competitive dynamics in an emerging technological field, and undercutting the relative advantages of legacy industrial leaders.

Chinese researchers and analysts view quantum technology as presenting an opportunity for China to reduce foreign dependence, gain leverage, and “leapfrog” the West.

“Quantum technology…is the only opportunity for our country to achieve ‘overtaking on the bend’ in the semiconductor field,” writes Chen Gen, a well-known Chinese science writer and analyst.

Or as an executive Origin Quantum, a leading Chinese quantum computing firm, put it:

“…In the future era of quantum computing, this situation [of China’s reliance on foreign high-end chips] will greatly change.”

In short, the quantum race is an asymmetric competition.

China’s recent quantum advances

Recent developments in China’s quantum industry highlight potential asymmetries it can leverage.

One asymmetry is the choice of technology.

There are several different technologies being pursued for realizing a quantum computer; trapped-ions and superconducting qubits are the two leading approaches.

IBM is going down the superconducting qubit route. In part, this is to build on IBM’s decades-long expertise and leadership in semiconductors. As IBM’s director of quantum systems Jerry Chow explained it to The Verge this week:

“…a lot of the work that we’ve achieved with even achieving a 100 qubits with Eagle a couple of years ago was because we had that deep-rooted semiconductor background.”

China, by contrast, is not a legacy semiconductor player. In addition, the superconducting quibit approach requires using super-fridges known as dilution refrigerators, which use helium to achieve the ultra-low temperatures required for quantum computing. Right now, China is heavily reliant on imports of these super-fridges and the helium re frigerant, mostly from the US—resulting in what tech outlet 36Kr calls an “upstream chokehold.”

That may be one reason why China is directing vast resources towards the trapped-ion approach. In February, Guokai Qudoor unveiled the country’s first modular trapped-ion computer. (In the US, IonQ and Honeywell are also taking the trapped-ion route.)

“State-led, enterprise-driven:” China’s classic playbook

Another asymmetry revolves around the role of state capital: leading Chinese quantum startups have extensive ties to and support from state-backed investors, and are often linked to government research facilities and institutions.

Take Shenzhen SpinQ Technology, which last month exported a superconducting quantum chip to Middle Eastern customer—the first such overseas sale for the country, according to state-owned Science and Technology Daily. A major shareholder of SpinQ is the state-owned Shenzhen High-Tech Investment Group.

Meanwhile, Guokai Qudoor is a “little giant”—companies selected and supported by the Chinese government for their potential to establish a leading position in critical industrial nodes. Numerous other Chinese quantum companies are also among the “little giant” rosters.

Assessing the quantum playing field

All this leads to some questions to guide further thinking and research. For example:

- Within the quantum industrial chain, broadly defined, what are China’s most critical dependencies on foreign inputs?

- Conversely: is the US reliant on China for certain nodes of its own quantum pursuit?

- What strategies should the US employ to safeguard and capitalize on its lead in quantum technology?

Weekly Links Round-Up

- The US needs to shore up its defense industrial base. A forthcoming inaugural report from the Pentagon will unveil a National Defense Industrial Strategy, and outline ways for the government to harness the agility of small tech firms and the heft of larger traditional companies. That could help the US build weapons more quickly and cheaply. (Politico, WSJ)

- One of the world’s biggest iron ore mines will begin production in 2025. So says Rio Tinto, an investor in the Simandou project. As Bloomberg reminds this week, however: “For many Western watchers it’s seen as a Rio project. It’s actually Chinese.”And the additional output, when it finally hits global markets, could boost Chinese pricing power over the raw material. As we noted back in March, Chinese industry analysis sees Simandou as a big win for the domestic steel industry. (Bloomberg, Force Distance Times)

- Chinese car exports to Europe may have to take a lengthy and costly detour. Fears of attacks against Israel-linked vessels in the Red Sea could force Chinese exporters to detour south around the Cape of Good Hope, potentially adding at least 20% to the cost of exporting a single car to Europe. (Caixin via Nikkei Asia)

(Photo by IBM)