Reshoring, especially from China, is essential to American resilience. Reshoring is also feasible. The trend is well under way with 260,000 returned manufacturing jobs announced in 2021, as a result of reshoring and foreign direct investment (FDI), and markets waking up to the imperative. Now, reshoring can be further accelerated via a well-designed government industrial policy.

In this piece I propose a framework and set of policy measures to level the playing field. These could bring the total reshored US jobs to 5 million, a 40 percent increase in manufacturing, and full American resilience. This approach focuses on reshoring jobs from China: To date, China has been the source of 44 percent of US reshoring – and is vulnerable to even more now as geopolitical decoupling risks grow and the cost of China exposure becomes more apparent. The opportunity needs to be seized: The US needs to reshore more from China while doing so is still a choice.

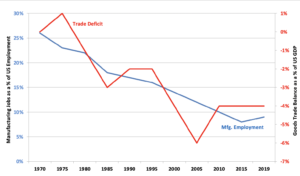

The US has a 1.1 trillion USD goods trade deficit. The country has a trade profile like that of a developing country with trade surpluses primarily in commodity minerals and agricultural products and large trade deficits in most high-tech products.

US Goods Trade Balance and Manufacturing Jobs (1970-2019)

Source: BEA trade data, FRED GDP data

The root cause of the problem is this: US manufacturing costs are not competitive. Companies source primarily based on price. The Chinese factory price is, on average, 30 percent lower than the US price, based on 180 cases of companies comparing U.S. and Chinese sources. The factory price of most US peer countries is 10 to 15 percent lower. As long as that huge price differential remains, and companies treat it at face value, the US trade imbalance will not improve – and therefore resilience will not either.

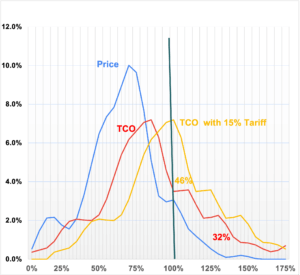

But there is a solution. That solution involves both changing company perspectives on price calculations and leveling the industrial playing field. On the first front, companies should be encouraged to source based on total cost of ownership (TCO), not just factory price. That means factoring in not only the purchase price of a good, but also, for example, added costs of trade remedies (e.g. Section 301 tariffs) and of logistics (e.g., shipping prices, inventory carrying costs, and risks of shipping disruptions). Adjusting for those costs radically increases the US win rate, e.g. from 8 percent based on price to 32 percent based on TCO.

Chinese Price and Total Cost of Ownership, Percent of US

Source: Reshoring Initiative TCO user database

On the second front, the US government should take measures that reduce the actual factory price gap to make more products more obviously reshorable. This would be a strategic approach to industrial policy. The alternative is a series of whack-a-mole, non-market measures that address surface-level industrial deficiencies rather than the larger systemic imbalance – for example, subsidizing chip foundries but not reshoring electronic product assembly, therefore remaining dependent on China to buy our chips, assemble them into infotainment systems and electronic medical devices, and sell back to us. Such a whack-a-mole approach amounts not only to missing the forest for the trees but also paving the way for those trees to be decimated in the long-run.

This leveling of the playing field demands a series of new or accelerated government policies.

First, the US should improve skilled workforce quantity and training to achieve the necessary increases in output and efficiency. The US can do so by offering apprenticeship loans, changing Labor and Education Department statistics to include data on apprentice graduates and holders of multiple credentials, and facilitating immigration of skilled workers.

Second, the US should reduce the value of the USD, using the Market Access Charge, developed by Dr. John Hansen and recommended by Clyde Prestowitz to the US-China Economic and Security Commission in April. The dollar’s current strength makes US exports uncompetitive, exacerbating both the deficits in the current industrial landscape and long-term inflationary trends when the USD ultimately collapses.

Third, the US should keep immediate 100 percent expensing of capital equipment – which expires on December 31, 2022 – to achieve competitive price and delivery. The US will lose more jobs to Chinese automation if it does not invest than it will to US automation if it does.

Fourth, the US should update the Department of Commerce’s Assess Costs Everywhere (ACE) Toolkit, which for the most part dates to 2012. The toolkit should include available estimates of the risks of severe disruptions, including a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, continued COVID Zero policies in Mainland China, and impacts of climate change.

Fifth, the US should address ballooning healthcare costs, including by controlling malpractice litigation and negotiating all pharmaceutical prices. Healthcare costs are built into company cost and thus price. The average employer cost for family insurance in 2021 was over 16,000 USD per year, about 8 USD per hour, which is higher than the average Chinese wage rate. Lowering healthcare costs means lower inflation and accelerated reshoring.

Finally, the US cannot delay because of inflation. About 30 percent of goods now imported from China could individually be sourced in the US without exacerbating inflationary trends if companies were to act and price based on TCO. And while reshoring might entail upfront investments, it is necessary to developing the economic resilience that in turn can resist longer-term inflationary trends.

Across the board, the US needs not only to work to make reshoring possible, but also to emphasize FDI, nearshoring, and friendshoring.

Reshoring is already underway. Including FDI, reshoring has already brought about 1 million manufacturing jobs back to the United States since 2010, with the rate of return growing from some 6,000 jobs per year announced in 2010 to 260,000 per year in 2021. Through 2018, reshoring was driven by nascent recognition of the logistical cost and inconvenience of offshoring and by rising offshore wages. Since then, the trade war, tariffs, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the increasing risk of decoupling with China have dramatically increased corporate recognition of the vulnerability of supply chains and the costs of their disruption – and therefore their enthusiasm for reshoring. That recent acceleration can be explained by a transformed geopolitical and geo-economic environment.

The US needs urgently to capture this window of opportunity. International industry is at an inflection point. Here is the chance to revive the US industrial base and, with it, US economic resilience and growth. It is time for the government to level the playing field and for companies to seize the opportunity to reverse the excesses of offshoring and globalization.

Harry Moser is the founder of the Reshoring Initiative. He was previously president of machine tool maker GF Machining Solutions for 22 years. His awards include: Industry Week’s and Association for Manufacturing Excellence’s (AME) Halls of Fame, SPE’s Mold Designer of the Year and Fab Shop Direct’s Manufacturer of the Year. He participated actively in President Obama’s 2012 Insourcing Forum at the White House and was a member of the Department of Commerce Investment Advisory Council 2019 to 2021. Harry is regularly quoted in the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and The New York Times, and seen on national TV and radio programs. He holds a BS and MS in Engineering from MIT and an MBA from the University of Chicago. More on his analysis on the potential for American reshoring can be found in his full testimony before the US China Security and Economic Commission from June 2022.

(Photo by Sasha Prasastika/Pexels)