Germanium and gallium have of late captured headlines worldwide, after China imposed export restrictions on the two critical minerals key to making semiconductors.

Getting far less attention is indium phosphide, a compound semiconductor material with high potential for widespread use in high-volume data transmission, telecommunications, autonomous driving systems, wearable tech, and smartphones—in short, the building blocks of our deeply connected, digitized, and high-tech world.

But China is eyeing indium phosphide as an opportunity to shake off dependence on foreign semiconductor technology, and in turn a point of leverage over global semiconductor supply chains.

“Break the foreign monopoly! China’s indium phosphide semiconductor industry ushers in opportunities for overtaking on the bend,” declared a headline in a 2022 article by Sichuan Guangheng Communication Technology, a manufacturer of optoelectronic devices.

The promise of compound semiconductors

First, some basics. There are three types of semiconductor materials: elementary semiconductors, which only contain a single element, like silicon and germanium; compound semiconductors, which are made of two or more elements, like gallium arsenide and indium phosphide; and wide bandgap semiconductors, like gallium nitride and silicon carbide.

Compound semiconductors can do things that single-element semiconductors cannot. That includes being more energy efficient and resistant to heat, and the ability to move electrons at much higher speeds, which means faster processing capabilities. As the chipmaking equipment company Applied Materials puts it: “Silicon semiconductors made possible today’s electronics industry; compound semiconductors will drive the next wave of advances, from 5G to robotics, more efficient renewable energy, and autonomous vehicles.”

There are two main kinds of compound semiconductors, gallium arsenide and indium phosphide. China dominates upstream inputs for both: in 2022, it accounted for 98% and 59% of primary gallium and indium production, respectively.

The production of indium phosphide wafers is more distributed: Japan’s Sumitomo and JX Nippon together accounted for 55% of global output in 2020, while the Beijing Tongmei Xtal Technology—the Chinese subsidiary of US wafer maker AXT—made up 36%, according to the latter’s prospectus.

Huawei’s bet on indium phosphide semiconductors

Chinese sources see significant advantages in indium phosphide. The outlet Semi Insights, for example, describes it as “more advanced than gallium arsenide, and could potentially promote high-frequency satellite development.” Meanwhile, demand for indium phosphide wafers is projected to grow rapidly, propelled by the need to power 5G base stations and data centers.

And Chinese manufacturers of gallium arsenide crystals and wafers are now actively working to build up indium phosphide capabilities.

One key player is Yunnan Lincang Xinyuan Germanium Industry Co., Ltd., or Yunnan Germanium for short. Its subsidiary, Yunnan Xinyao Semiconductor Materials Co., Ltd., kicked off production of indium phosphide monocrystalline wafers in April 2022. The company has a significant backer: telecommunications giant Huawei’s venture capital arm, Hubble Investment, which in 2021 took a nearly 24% stake in the firm.

“Huawei’s investment in Yunnan Xinyao Semiconductor Materials Co., Ltd. is to safeguard its supply chain security in semiconductors for optical communication,” writes one Chinese analyst.

According to Yunan Xinyao Semiconductor Materials, the company as of May 2023 has an annual production capacity of 150,000 two- to four-inch indium phosphide wafers, and supplies the semiconductor materials to around 90 clients.

And in another sign of indium phosphide’s strategic importance for China: to Yunan Xinyao Semiconductor Materials is a designated “little giant,” companies selected and supported by the Chinese government for their potential to establish a leading position in critical industrial nodes.

Robust future demand for indium phosphide, writes Ali Jaffal of market research firm Yole Intelligence, “could elevate it from its niche market and propel it to a prominent position.” The question is whether China will manage to ride the wave of this rising technology to newfound semiconductor dominance.

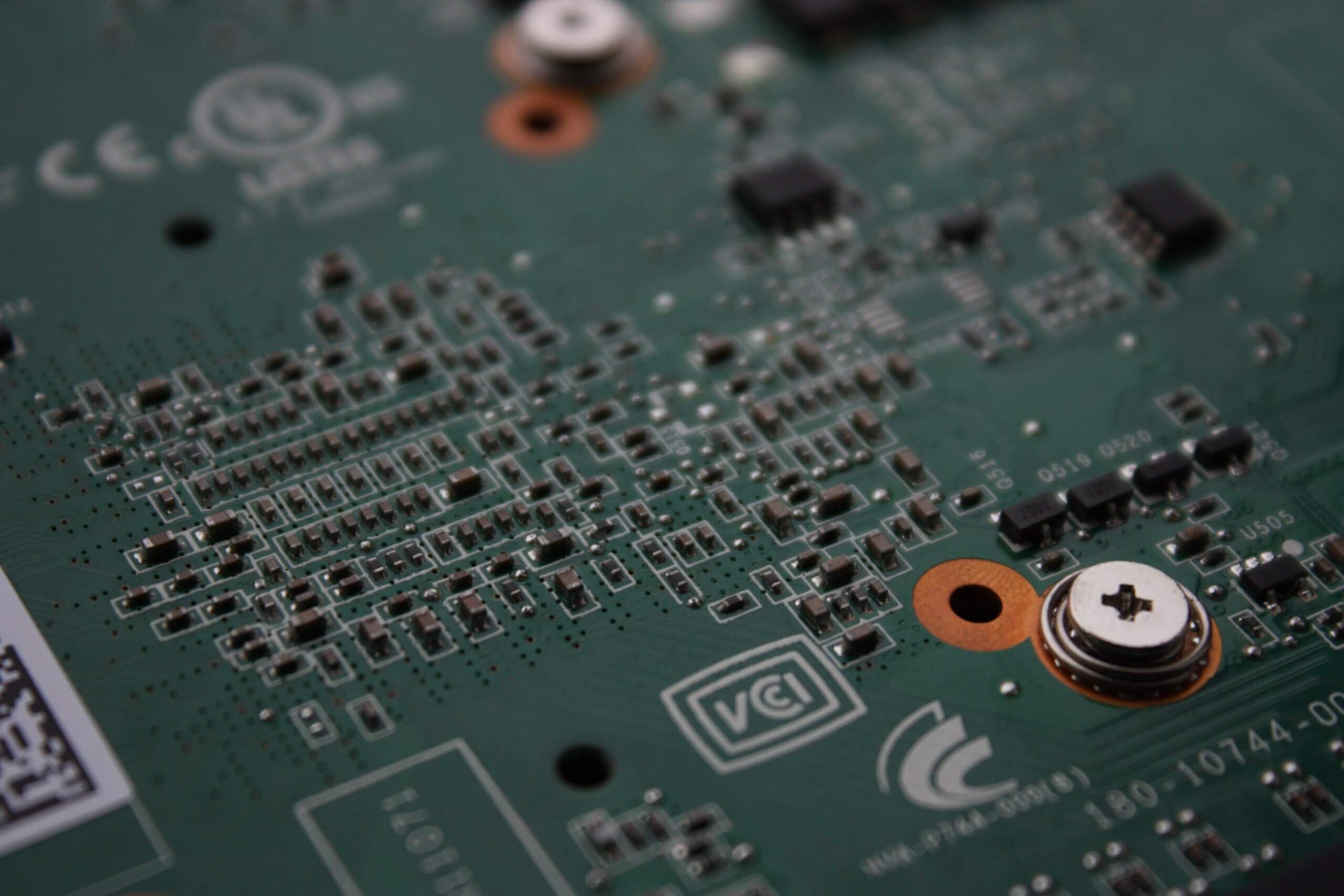

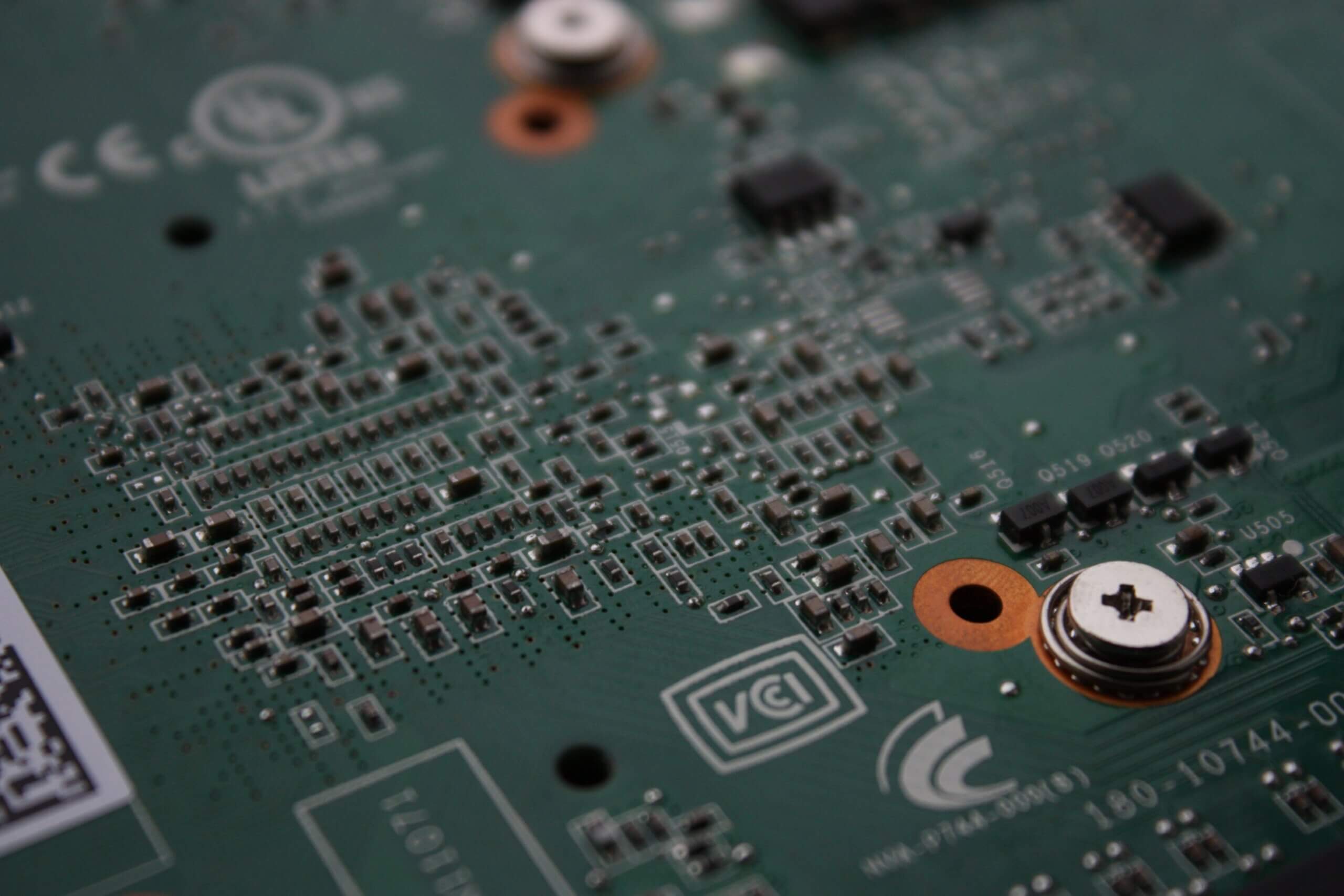

(Photo by Shawn Stutzman/Pexels)