Dell announced at the start of the year that it intends to stop using semiconductors made in China by 2024 – and that it is encouraging its suppliers also to reduce their dependence on Chinese components. This is great. It is a sign of a major US company waking up to the risks posed by reliance on China. It could even be an indicator of a broader recognition by the US private sector.

But Dell’s move is also wildly insufficient given the breadth of the company’s ties to and reliance on China – and the latent costs those carry. The company’s supply-side exposure to China extends well beyond semiconductors. As of 2021, 85% of Dell’s supply chain was in China. So was 75% of its productive capacity. Phasing out made in China semiconductors suggests a recognition of today’s market and geopolitical threats — that Beijing leverages its role as the world’s workshop to steal technology, cement dependence, and support its own champions at the expense of international companies, markets, and security. But what about Dell’s manufacturing plants, maker laboratories, and research and development centers in China?

Dell’s move is great. But it is also wildly insufficient given the breadth of the company’s ties to and reliance on China – and the latent costs those carry.

Nor is Dell’s China problem – and that of US and international industry more broadly – just a matter of supply-side exposure. According to a 2022 report published by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, in its effort to court Beijing, Dell has supported Chinese government entities developing national surveillance programs and cutting-edge software and electronic tools. Dell has assisted Beijing in defining its industrial policy. Dell has also partnered with China’s leading research institution on surveillance- and military-relevant AI and computing capabilities. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Chinese media calls Dell a “foreign-owned local enterprise.”

All of these realities pose real risks to security and prosperity among democratic and market-based actors. Ties to China’s production base and market grant Beijing access to advanced technology that it can leverage to repress its citizens, build its international power projection, and further hollow out global industrial capacity. These relatively long-term challenges have already been proven out.

These realities also pose real, acute risks to Dell. The company is surrendering its technology and supply chain to a hostile government intent on overtaking it – all while it relies on that government for market access.

For decades, US companies have been swayed by the siren song of cheap production and rapid market growth in China. Dell could be at the vanguard of reversing this trend. Or it could be putting a band-aid on a bullet hole.

If Dell really is waking up, to its own interests and those of the world, its chip announcement should be just the beginning. We should see this announcement followed by Dell production facilities moving out of China, the closure of its research and development centers in the country and shuttering of its partnerships with Chinese government and military entities. We should see Dell looking for new suppliers, outside of China – and re-orienting its revenue model to focus on trusted markets.

And if US industry is waking up, too, we should see Dell’s peers follow suit: The Same Victims of Communism Foundation report found similar exposure to the Chinese system on the part of other major US industrial players, ranging from General Electric to Microsoft to Intel. All should be cutting that exposure, and under public and market scrutiny until they do so.

Meanwhile, other companies in sectors that China prioritizes should be following this trend closely and taking proactive action. This is particularly true for fields that Beijing identifies as national priorities, including the auto, pharmaceutical, agricultural, information technology, and aerospace industries.

For decades, US companies have been swayed by the siren song of cheap production and rapid market growth in China. They have ignored the long-term costs of those boons – namely the reality that the Chinese market is only a realistic opportunity for Chinese champions. All others end up, ultimately, the spoils of war. Dell could be at the vanguard of reversing this trend. Or it could be putting a band-aid on a bullet hole.

Nate Picarsic is a co-founder of Horizon Advisory, a supply chain and geopolitical risk startup, and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. His commentaries on industrial innovation have been published in outlets ranging from TechCrunch to Defense One.

Emily de La Bruyere is a co-founder of Horizon Advisory, a supply chain and geopolitical risk startup, and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Her analysis has been cited in outlets including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post.

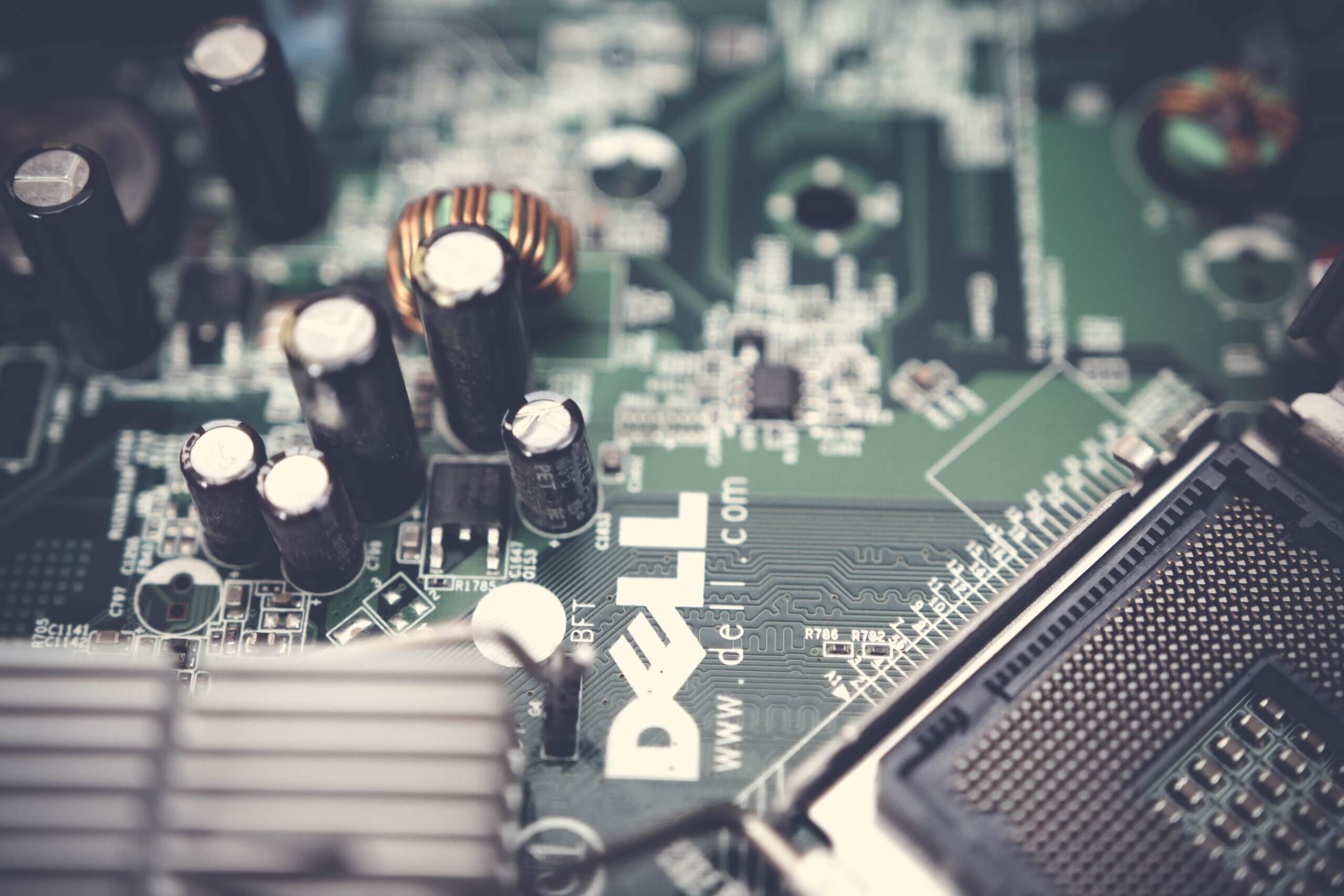

(Photo by Pok Rie/Pexels)