Amid Global Energy Squeeze, China and India Refocus on Coal

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, the world faced a major energy crunch – a function of economic rebound from the pandemic, a cold winter, and delivery snarls. Now, Russia’s aggression is turning squeeze into crisis. And with the European Union announcing this week that it is considering banning the import of all Russian oil, prices are skyrocketing, beyond even their earlier skyrocketing. LNG prices on the US benchmark Henry Hub jumped more than 10% over the past week alone; gasoline is sitting at a US average of 4.23 USD/gallon.

But the energy squeeze extends beyond the obvious suspects of oil and gas, and with major geopolitical, economic, and environmental implications. Take, for example, coal, which just a year ago was viewed as on the verge of extinction: Prices of coal are expected to be 80% higher this year (p.11) compared to 2021 (in no small part thanks to Europe’s and Japan’s bans on imports of Russian coal). And in response to those projections, China and India – the world’s two largest producers, consumers, and importers of coal — are rushing to secure their supply. On the one hand they are increasing production. Both countries have said they will boost domestic coal output, and China’s central bank this week announced 100 billion RMB of credit lines to support the domestic coal industry. But on the other hand, China and India also appear intent on stockpiling. India has told state and private sector utilities to speed up imports, while China has just cut coal import tariffs to zero. Combined, the two countries’ moves to boost coal purchases could further drive up prices of the fuel, in an energy sector many are ignoring, and further bolster their leverage over international markets.

As Russia Runs Short on Alumina, China Steps In

Russia is the world’s second largest aluminum exporter. However, aluminum production requires alumina, also known as aluminum oxide, and Russia may now be running short. Australia and Ukraine have in the past been Russia’s top sources of alumina, making up 68% of total alumina imports into the country in 2020, according to UN Comtrade data. But now, Australia has banned exports to Russia, and a Russian refinery in Ukraine that supplies Russian aluminum smelters has halted operations.

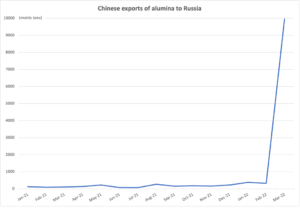

With increasingly limited access to alumina, Russia appears to be turning to China. In March, China exported 9,950 metric tons of alumina to Russia, nearly 10 times more than what it shipped in the same period last year – even as China’s other exports to Russia have shrunk. These exports don’t exactly resolve Russia’s alumina quandary; China is still only offsetting a small fraction of the 275,000 metric tons that Russia imported monthly from Australia and Ukraine prior to the invasion, and unlikely to up the figure as it needs alumina for its own smelters. However, the jump in alumina exports from China to Russia underscores an unintended consequence of the economic warfare between Russia and the West: In cutting off Moscow, the West may be turning Russia into a resource, and production, colony of China.

Source: Chinese General Administration of Customs

The US Government Makes Plans to Sell High, Buy Low

Following US president Joe Biden’s announcement in March of the largest ever release of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR)—a move that will add 180 million barrels to the market over the next six months—the Department of Energy (DOE) this week announced a plan to refill the SPR.

Specifically, the buyback process will start taking bids this fall, with expected delivery in “future years.” Importantly, crude purchases for the SPR refill will be conducted via a “competitive, fixed-price bid process,” rather than through the existing index-pricing model, one that adjusts final crude sale prices based on index prices at the time of delivery. What does this mean, in practice? The DOE will buy what are effectively futures contracts: It will lock in lower prices now for delivery later, therefore eliminating the guesswork around how much it will cost to refill the SPR – all while encouraging more production in the near term by giving producers a clearer idea of how much demand to expect, at what price. The big looming question: Can Washington deploy the other carrots necessary to encourage production, all along the energy value chain?

European Rare Earths for European Car Parts (Kind Of)

The German auto parts maker Schaeffler last month signed a raw materials deal to secure rare earth oxides from Norwegian company REEtec in order to make permanent magnets for EV motors. This is reportedly the first deal by a European carmaker to source rare earths from Europe. It is being lauded as a pioneering, concrete step in the bloc’s efforts to reduce reliance on China.

That said, it would certainly be a stretch to describe this as a fully European supply chain: The company boasts advanced separation technology but is not a rare earths miner. It sources rare earth carbonates from Canada’s Vital Metals, then processes those into oxides for sale to Schaeffler. But for all the caveats, this supports the story we’re seeing in lithium: With the EV revolution throwing critical mineral inputs into the spotlight, automakers are increasingly investing in vertically integrated, or at least vertically coordinated, value chains.

Not One to Waste a Crisis, Malaysia Abhors a Cooking Oil Vacuum

Last week, Indonesia implemented a ban on exports of crude and refined palm oil, threatening to further disrupt global cooking oil supply, already thrown into disarray by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Russia and Ukraine are the world’s top two exporters of sunflower oil). Now, Malaysia has announced that it intends to step into the gap. It aims to leverage the global cooking oil shortage and political tensions in Europe to expand the country’s global palm oil market share, and claim what it sees a wide and lucrative market opportunity. As the Malaysian commodities minister put it bluntly, the government “will not want to waste a good crisis.” Malaysian crude palm oil prices are up 45% this year, though they have retreated slightly this week on hopes of a production rebound and a potential easing of the Indonesian ban.

(Photo by Pexels)