An imperfect storm of global pandemic, land war in Europe, and, undergirding all, great power competition waged in international markets have thrown the US economy – and assumptions undergirding it – into disarray. But with crisis comes opportunity. These unprecedented stressors have created the conditions for a resurgence of investment in domestic industry and the emergence of new models for public-private industrial coordination to support it.

Below is one such example, a case of operational success at a time of enormous pain and uncertainty. This case underscores both how feasible new, measured, and effective responses to chaos can be and the outsized rewards that can result.

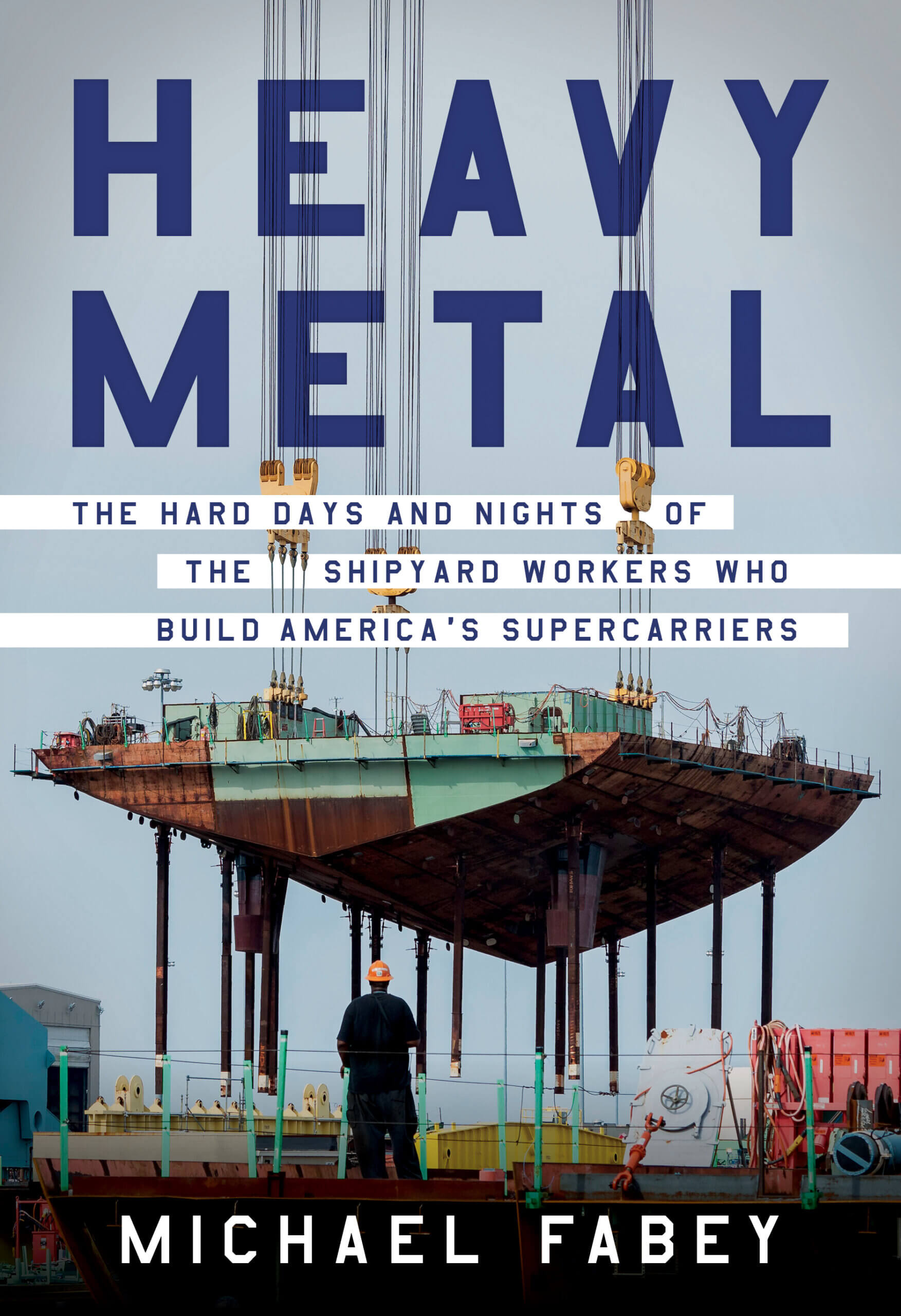

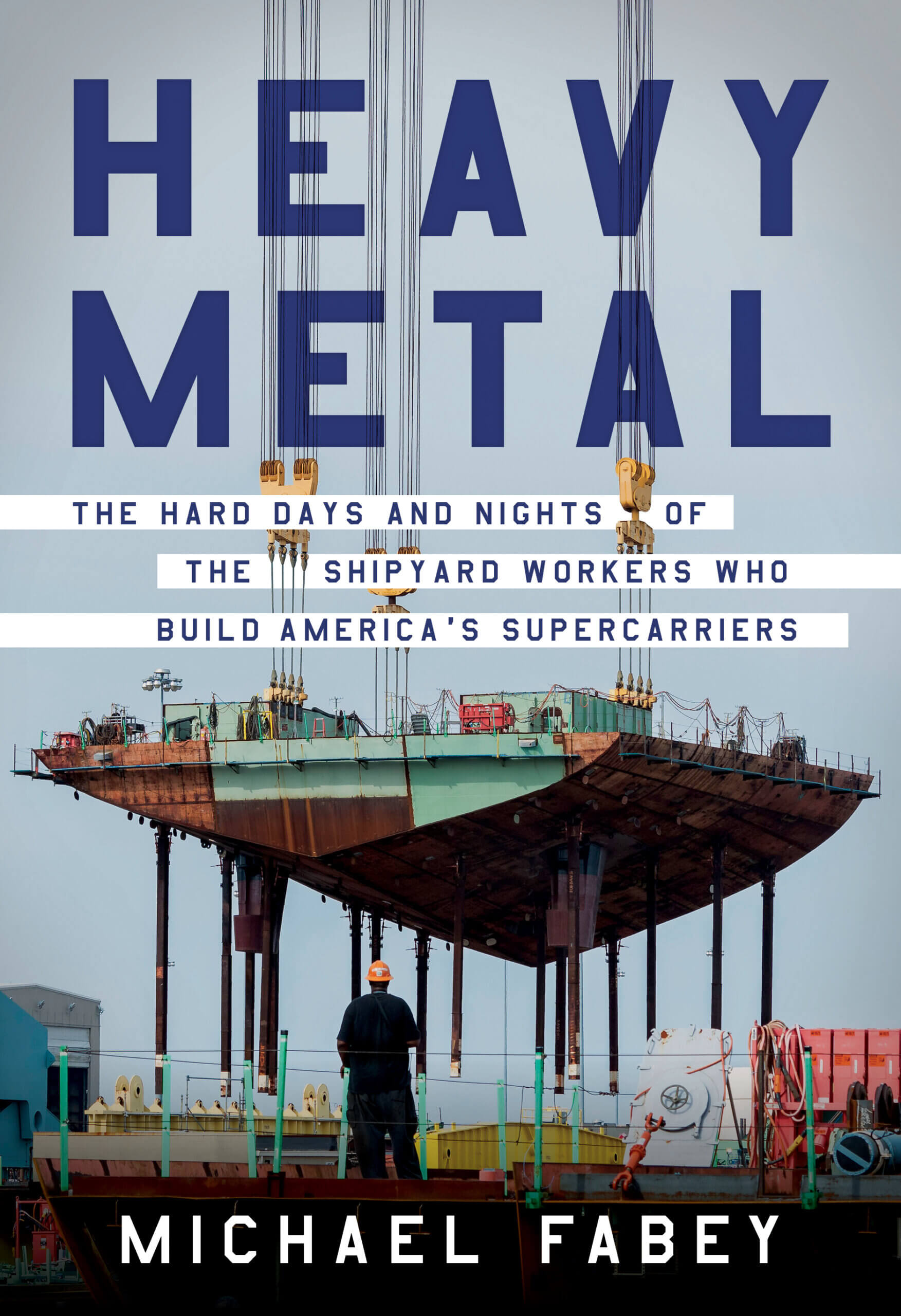

The below is excerpted, for Force Distance Times, from Michael Fabey’s 2022 Heavy Metal: The Hard Days and Nights of the Shipyard Workers Who Build America’s Supercarriers – a story of not only American industrial dynamism but also American can-do at a time when doing seemed impossible. Heavy Metal captures an indelible moment in the history of a shipyard, a city, and a country. Michael Fabey is the Americas naval writer for Jane’s and the US editor for Jane’s Fighting Ships. He has reported on military matters throughout his career, writing for publications ranging from Aviation Week to Defense News.

Covid-19 dominated the minds of waterfront steelworkers on the James [River in Virginia in early 2020]. After the governor closed the schools in March for the academic year, homes became community classrooms, daycare centers and, with everything shut down, round-the-clock self-contained worlds. In Newport News, parents became frantic about childcare, especially those who worked in the shipyard, whose work the government deemed essential.

“The conditions seem to change every day, along with the expectations placed upon us at work and the options we have to protect ourselves, our co-workers and our families,” Local 8888 said in its April edition of the steelworkers Voyager newsletter. “Many of us do not know what to expect going forward.” The Union noted, “The shipyard will not shutdown. . . . We at the Union represent the workers to remind them that those things depend on our continued health and well-being as well as the risk we incur every day we come to work in spite of the CDC and Governors Guidance to ‘Stay at Home.’ . . . In order to protect ourselves and our families, particularly those at increased risk, many of us have reluctantly had to stay at home.”

Yes, other businesses deemed essential voiced the same kinds of concerns, but none of them faced the scope of risk by those on the waterfront, with tens of thousands of workers, sailors, and others all cramming into one waterfront space. The yard offered some help straightaway, and the workers welcomed it …The biggest issue at most of the yards, executives said, concerned childcare. Schools, after-school programs, and other childcare centers closed throughout the country. When Virginia suddenly closed schools, yard workers from the waterfront to the boardroom pulled double and triple duty as remote teachers and homecare providers, with no alternatives. The yard gave people the flexibility to stay home, without suffering any consequences, providing they proved extenuating circumstances. The yard guaranteed their jobs, if the workers stayed out to take care of things …

The most anticipated revelation in Hampton Roads … was what Newport News Shipbuilding president Jennifer Boykin planned to do at the shipyard to keep operations running while ensuring a safe workforce. Unlike [carrier John F. Kennedy Commanding Officer Captain] Cherry Marzano, she could not abandon the Kennedy or any of the ships in the yard. She needed to act quickly but not rashly. She opted to rely on the collective wisdom of the smart, dedicated shipbuilders to chart a good, solid, safe course.

One of the first decisions she made was to be honest, open, and transparent with workers and the community about cases in the yard, infection concerns, and so on. She would be publicly berated several times for that decision, but the e-mails she received told her she did the right thing.

For work on the Kennedy and other ships, managers assessed work they needed to do, the workforce on hand, and what trade-offs they needed to make. They faced not only a shortage of labor, but also of other resources. Boykin wanted to know what they needed to do to protect workers but keep Navy work moving ahead and ensure the yard’s viability when it all ended. She prepared for the worst and developed a plan to survive with the workforce and business intact. To get that stark true picture, she needed honest input from her seasoned pros. No other shipyard would be as taxed during this Covid catastrophe as the one in Newport News. While every yard braced for challenges, Newport News Shipbuilding faced a particularly complex set of concerns when Covid-19 outbreaks started.

First, the yard made sure it identified its priorities correctly—and that those priorities meshed with Navy’s. The yard focused its workers and resources on ships being fixed or overhauled. For Boykin and others running the shipyard, the number-one concern remained ensuring workers’ health and safety. Trying to keep a workforce on the waterfront safe during a pandemic, when folks needed to work in such close quarters while building and repairing ships, promised to be the biggest challenge the yard had ever faced. The yard needed to figure out how to accommodate the changes needed for the remaining workers to complete their jobs, in the yard and out.

To meet CDC guidelines, thousands of designers, engineers, and other yard workers who generally worked in offices now worked remotely from home, and they required the IT department to create greater digital accessibility than was ever required previously—access among workers routinely transmitting large digital files. That proved relatively easy compared to the measures the yard took for the steelworkers who absolutely had to enter the yard—after all, you can’t Zoom a weld. To get to the waterfront, shipbuilders queued at the gates, and once inside, they needed to access tools, food, and other daily resources, creating other points to gather and wait.

To help develop action plans to address those needs, while keeping the yard operational and Covid-19 compliant, on April 2, yard president Jennifer Boykin established a Covid-19 Crisis Action Group (CAG) of team leaders from all over the yard to work on recommendations on how to safely and efficiently operate during the pandemic. A new vice-presidential steering committee considered recommendations and sent ones it approved to Boykin. This prevented VPs from coming up with individual plans for their own operations and interfering with overall company interests. Four sub-teams formed under the CAG helped the yard respond to the pandemic quickly and with some agility.

The teams met two to three times daily. Each of the teams focused on a different area: mitigating the virus risk to employees; adjusting production to meet customer’s needs despite the expected workforce cuts; ensuring yard viability; and protecting job security through and after the pandemic.

The above is excerpted, for Force Distance Times, from Michael Fabey’s 2022 Heavy Metal: The Hard Days and Nights of the Shipyard Workers Who Build America’s Supercarriers – a story of not only American industrial dynamism but also American can-do at a time when doing seemed impossible. Heavy Metal captures an indelible moment in the history of a shipyard, a city, and a country. Michael Fabey is the Americas naval writer for Jane’s and the US editor for Jane’s Fighting Ships. He has reported on military matters throughout his career, writing for publications ranging from Aviation Week to Defense News.