The week’s news recap: Across wheat, gas, steel, the shortage crisis has calmed – but (largely) because of dropping demand, not rising supply. With manufacturing slumping, future food production threatened, buffer eroded, what happens next? Plus: Storm clouds gather in the UK and China throws a temper tantrum.

THE BIG BITE

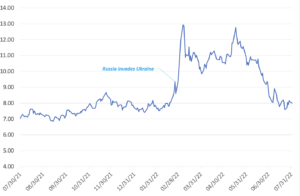

Wheat prices relax, but is this the calm before the storm?

The first shipment of Ukrainian grain left the port of Odessa early this week, followed on Friday by the departure of the first convoy of grain-laden ships. Barring disruptions and a breakdown in the Ukraine-Russia 120-day deal brokered by Turkey and the UN, all 18 million tons of grains trapped in Ukraine since the war will finally get exported. Needless to say, this could help to alleviate the global food crisis. Plus, wheat prices have returned to pre-war levels – while overall food costs plunged nearly 9 percent in July to hit their lowest level since January, before Russia blockaded Ukraine’s ports.

These developments offer a much-needed breather. However, they do not spell crisis avoided. Yes, Russia is allowing shipments of grain from Ukraine. But Moscow maintains its ability to hold Ukraine’s food supply hostage. What happens if Russia decides to turn the screws? And that’s just in the immediate. Looking forward, a war-torn Ukraine will significantly under-produce in the months and even years ahead. High global fertilizer prices also risk undermining future food supply.

Moreover, extreme weather continues to introduce new uncertainties. Right now, the lack of rain in India, which accounts for 40 percent of global rice trade, is threatening the country’s production of the staple. Rice was spared much of the war-induced price surge that has afflicted wheat; a production crunch would push up both domestic and export prices. That would complicate India’s fight against inflation. It could even prompt the country to restrict exports, with implications for political and economic stability in rice-dependent Asia.

Wheat futures contract trade on the Chicago Board of Trade, USD/bushel

Source: FactSet

The problem isn’t limited to India. Droughts across western Europe – particularly Italy, which represents around 50 percent of total EU production – are predicted to reduce the bloc’s milled rice production by 21 percent this year. In short, skyrocketing global food prices preceded the war in Ukraine. Deal or no deal, a perfect storm (or lack thereof) of pressures risks continuing to threaten supply, with ripple effects aplenty.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSNo plus-sized increases from OPEC Plus

The White House had desperately hoped that the OPEC+ meeting this week would lead to a sizeable increase in oil production. Instead, the group responded with one the smallest oil production increases ever, announcing on Wednesday that it will pump an additional 100,000 barrels per day next month. Compare that to is commitment in June to boost output by 648,0000 barrels per day in July and August. This amount is unlikely to do anything to cool crude prices. But the problem here isn’t so much unwillingness as inability. Even if OPEC+ had pledged a bigger production hike, it is unclear if its member states would have had the capacity to pump more. In May, OPEC+ pumped nearly 3 million barrels a day less than its collective production target, stymied by slowing production in Russia, chronic problems in Nigeria and Angola, and, more broadly, limited recent investment in the oil sector’s development. Saudi Arabia, which is the member with the greatest spare capacity, is nearing its pumping limit.

That said, crude prices have already dropped significantly in recent months – in large part thanks to decreasing demand. Global slowdown, which seems increasingly likely, will continue the trend. It’s mixed news, certainly. But could such a slowdown be the opportunity that the US needs to launch much-needed investment in production, at home and abroad?

Gas export curbs down under?

The oil question is just one part of today’s larger conundrum. The gas market is thornier yet. Australia, one of the world’s biggest gas exporters, is considering restricting exports of the fuel as the country struggles to cope with domestic shortfalls and surging prices. A decision is expected in October. If curbs do kick in, that could roil an already tight global gas market and push up prices for consumers worldwide. Cash-strapped countries like Bangladesh, already facing a gas shortage and the prospect of several years of rolling blackouts, would be hit hardest. Europe wouldn’t do so great either.

But remember: Australia is not short of gas, per se. The problem is that global energy companies exporting gas from Australia’s east coast have not been required to reserve a set amount for the domestic market at regulated prices, and domestic consumers won’t pay the high prices that the firms can fetch on the global LNG market.

The world’s steel engine stalls

China is importing, exporting, and producing less steel as a property crisis – compounded by COVID-19 lockdowns and corresponding slowdown – threatens the country’s construction-fueled growth model. Executives are warning that as many as one-third of China’s steel mills could go belly-up. The slumping steel demand has weighed on Chinese steel prices, with the country’s steel price index down 14 percent from the year’s peak. Futures for iron ore, a key ingredient for making steel, have also declined. The country is imposing caps on production across the steel value chain. And while a massive stimulus driven by infrastructure spending could prop up steel demand, Beijing has thus far signaled unwillingness to back such a large-scale investment.

The bigger question though is what a Chinese steel slump means for the international market. Right now, the story is one of stumbling international prices thanks to weak demand. But steel is an industrial necessity and China is the engine of international steel supply: In 2020, China produced more than half of the world’s steel. If production really does slow significantly, and mills do go belly-up, the next chapter of this story could be one of new supply crisis, globally, and skyrocketing prices with it.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

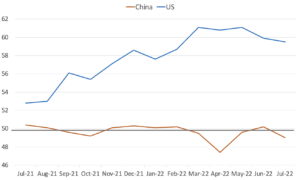

MARKETSGlobal manufacturing slump – in an era of shortage

Factory activity worldwide is taking a tumble. China saw an unexpected contraction in manufacturing, recording 49 in its manufacturing purchasing manager’s index (PMI) versus an expected 50.4. That shouldn’t come as a surprise: June offered a one-off boost as the worst of China’s COVID-19 lockdowns lifted. However, gloomy economic fundamentals remain unchanged and firms are loathe to invest and hire. Meanwhile, factory activity also shrank across Europe and in South Korea and Taiwan. The US is faring better: Growth in factory activity slowed, but less than expected. Overall, the warning signs are clear. Global demand is flagging, squeezed by tightening monetary policy and higher commodity prices. Therefore, production is too. But it’s a strange dynamic considering that the reason for tightening monetary policy and higher prices was, to begin with, insufficient production: Interest rate hikes might have been be the logical or necessary response to soaring inflation, but they appear to have created the conditions for a meet at the bottom dynamic; a supply-demand alignment at slowdown, rather than supply rising to rise to meet demand.

US and China, manufacturing purchasing manager’s index

Source: Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, Institute of Supply Management

Just another curveball: Red hot US jobs market

The latest US jobs report blew past economists’ predictions, showing an increase of 528,000 jobs in July. This marked a milestone: The 22 million jobs lost early in the pandemic have now been fully recouped; unemployment is now down to 3.5 percent, a half-century low. It also messed with markets: Investors know that for the Fed, a strong labor market may incentivize continued rate hikes to tame inflation.

How does the unexpectedly robust jobs growth square with growing recession fears? For one, interest-rate-sensitive sectors like housing, finance, technology, and retail are laying off workers. And while jobs growth has accelerated, the labor-force participation rate—or the share of adults working or seeking a job – has decreased slightly to 62.1 percent. That’s pushing up wages as there are far fewer workers for the jobs that employers want to fill.

A cloudy economic forecast in the UK

The Bank of England this week raised interest rates by 50 basis points to 1.75 percent, its steepest hike in 27 years. This follows similarly aggressive recent rate increases from the European Central Bank and the US Fed. And more such aggressive hikes may be coming as the UK expects to see inflation top 13 percent by year end. Worse, the UK is likely more exposed to economic headwinds than the US or the eurozone. Data from the IMF shows that low-income British households will be the second-hardest hit in the world by rising energy prices, behind Estonia. Unemployment is rising, inflation will remain high, and household incomes will take a hit. To top it all off, the BoE is forecasting a 15-month recession starting later this year.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSPelosi goes to Taiwan, and Beijing goes ballistic

Nerves were high and investors jittery as US House speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan as part of her Asia trip this week. Beijing made a show of military bluster in retaliation; the immediate result was choppy trading – and gold prices hitting a four-week high as investors sought sanctuary. More interesting, though, if perhaps underappreciated, are the tools of economic coercion that Beijing deploying as part of its temper tantrum. China levied trade bans, a favored economic weapon, against Taipei, targeting food products in particular. Vis-à-vis the US, Chinese battery giant CATL has delayed announcing a multibillion-dollar plant in North America, citing the Taiwan tensions.

Some editorializing: From the Chinese perspective, this is largely a manufactured crisis; an opportunity to exact concessions from the US and international system, while stirring up nationalistic fervor at home. But that doesn’t make the development any less significant. On the contrary, this reveals a newly aggressive Beijing, willing to throw its weight around – and lean on the leverage it has developed over the international system – to reshape the global status quo. Expect more temper tantrums like this to continue, and China to use them to advance its strategic agenda. Expect that all the more if the US shows itself inclined to back down.

(Photo by Pexels)