China pivots on Zero COVID as the G7 price cap on Russian oil exports goes into effect. And that’s just one example of a new move to values-aligned trade blocs. Plus: The upward trajectory of lithium battery and tin prices, Russian coal exports, and Germany’s efforts to diversify away from China.

THE BIG PIVOT

China’s pandemic about-face

China is rapidly dismantling its zero-COVID industrial complex. Party propaganda has shifted into overdrive to reverse the official narrative of the past three years — that draconian lockdowns are a necessary price to protect the basic human right to life, and are price that the authoritarian CCP, unlike democracies, is able to pay. (And, fun fact, recent reporting suggests that this is turnaround is not only a function of hot-button developments like the widespread protests of recent weeks, but also of pressure from the Foxconn founder, who wrote a letter arguing that strict COVID controls would undermine Beijing’s central position in global supply chains.)

Now that China is easing pandemic restrictions, a surge in cases and deaths will inevitably follow. Where does that leave the grand bargain that the Party has forced on its citizens since 2020?

For now, Beijing is opting for a tried and tested strategy: Control the narrative. That means trotting out experts to declare that SARS-CoV-2 is, in fact, not so bad after all — never mind the drastic lockdowns, shutdowns, and forced quarantines of the past three years. To give an example: Zhong Nanshan, the famed respiratory disease expert who helped shape Beijing’s COVID strategy, told state media on Friday (Dec. 9) that the Omicron variant was “not scary” and that 99 percent of all patients would “fully recover” within ten days.

As Beijing pivots from maximizing to minimizing the COVID threat, the country is likely to follow a pandemic trajectory much like that of other countries: Heightened deaths (both COVID-related and not), a costly epidemic of long COVID, increased pressure on the health system, and an appreciable loss of labor productivity, for example. And a wildcard: China’s elderly are notoriously under-vaccinated. Will mass COVID deaths among that population spark social unrest?

The economic trajectory is less clear. China hopes to achieve 5 percent GDP growth next year; JPMorgan analysts think it’s possible with a pivot away from COVID Zero. That’s optimistic given where the country’s economy is now: November saw a worse-than-expected downturn in trade, with exports and imports plunging 8.7 percent and 10.6 percent, respectively — far more than the 3.8 percent and 7 percent analysts had forecast. And there’s the lingering question of whether a surge in COVID deaths might lead Beijing to backpedal on easing restrictions. But here’s one thing we can count on: If Beijing is expending the reputational capital to reverse its COVID policy for the sake of economic growth, it will likely put its money where its mouth is, launching new incentives, investment projects, and plans to hit desired targets.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

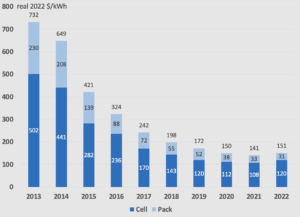

FACTORSLithium battery prices buck historical trends

For the first time since 2010, prices of lithium batteries rose in 2022 to 151 USD per kilowatt hour, a 7 percent year-on-year rise driven by soaring costs of raw materials and battery components. The price increase defies over a decade of price declines. And BloombergNEF expects prices to remain at similar levels in 2023. That said, prices of lithium itself — at record highs after quadrupling since September 2021 — are set to retreat as new supplies come online and EV sales slow. However, that doesn’t change the macro reality that over the years to come, lithium demand is poised significantly to outstrip supply.

Carmakers are positioning accordingly. Chinese EV maker BYD is in talks to enter a lithium mining project in Chile, and also eyeing prospects in Argentina and Africa. Plus, as we mentioned last week, automakers in the US, EU, and China are investing in research and production of sodium-ion batteries, hoping to develop a new branch of the electric vehicle industry as costs of lithium-based energy storage rise.

Volume-weighted average lithium-ion battery pack and cell price split, 2013-2022

Source: BloombergNEF

Don’t forget tin

While lithium often steals the spotlight, a shortage in tin is lurking. The International Tin Association estimates the world will need an additional 1.4 billion USD in investments to deliver an additional 50,000 tons of tin per year by 2030 to feed growing demand. At present, nearly half of tin is used as solder in circuit boards. And as Reuters points out, the accelerating shift towards an Internet of Things world will mean greater demand. So will increased use of solar panels and batteries, which also require tin.

The additional wrinkle: Tin prices are extremely volatile, making long-term investments difficult: The London Metal Exchange’s three-month tin contract shot above 50,000 USD in March, plunged to below 18,000 USD in November, and is now back up above 24,000 USD.

Russian coal exports rebound

Russian seaborne coal exports have jumped to near record levels: 16.6 million tons in October, just slightly below June’s levels, which were themselves at least a five-year-high. The rebound follows the European Union’s decision in September to ease restrictions on transporting coal, thereby making it easier to route volumes to Asia. And use of coal has soared as countries scramble for fuel supplies in a tight and volatile global natural gas market. China in particular has been a big buyer of Russian coal – and though import volumes slipped in October, they are rising again as the country stockpiles for the winter.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSOil prices capped

The G7’s 60 USD price cap on Russian oil exports took effect on Monday (Dec. 5). First, what this means: Only Russian oil sold at a price equal to or less than 60 USD per barrel can be shipped to third-party countries using G7 and EU tankers, insurance companies, and credit institutions. The price cap is intended to limit Russia’s ability to finance its war on Ukraine – while preserving both international access to critical energy supplies and the maritime insurance industry. Effectively, this is an effort to walk back the aggressive sanctions imposed by the EU earlier this year, and corresponding pain inflicted on the European market, without fully caving to Moscow.

The big question is whether the theory behind the price cap holds in reality, and in a reality of geopolitical conflict. Moscow has said it will not sell to countries that implement the price cap, even if that means it has to cut production. This could be a bluff. But remember that the very existence of the price cap underscores quite how much leverage Russia has over the international system.

Then there are subtler and unintended complications from the new price cap regime. For example, a traffic jam of oil tankers formed off Turkey this week as authorities in Ankara demanded that insurers prove that their ships were fully insured.

The US and EU consider emissions-linked tariffs on Chinese metals

The White House has a proposal for Europe: The Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum, an international consortium to promote trade in aluminum and steel produced with less carbon emissions and to impose tariffs on those metals produced in China and other countries that aren’t members of the group.

It’s an idea that the US and EU have been discussing since last year. The concept paper Washington shared with Brussels this week offers more concrete details. Though the proposal is still in its early stages and it’s unclear how it will be received, it’s another indication – especially amid price cap news – of the reconfiguration of global trade relations: Less unfettered globalization, more values-aligned trade blocs.

Meanwhile, the US and EU are also looking at potentially taking joint action against Beijing’s subsidies for its medical devices industry. A joint statement from the two governments cited their “shared concerns about the threat posed by a range of non-market policies and practices” supporting Chinese medical devices companies. Chinese media has likened the country’s heavy reliance on high-end foreign medical equipment to its dependence on imports of advanced semiconductors and chipmaking machinery.

Germany wants more investment in Africa

Trending up: Africa. Trending down: China. That’s the approach Germany is taking with its state guarantees for domestic companies’ investments in foreign countries. Economy minister Robert Habeck said this week that Berlin will provide “additional incentives to invest in regions like sub-Saharan Africa where we want more German investments and more German trade” as the country seeks to diversify its economic relationships and reduce exposure to China.

Habeck’s comments come just weeks after Germany made changes to its investment guarantee scheme to expand the number of countries covered, and put in place a new guarantee ceiling of 3 billion euros (3.1 billion USD) per company per country. Earlier this year, Berlin refused to grant investment guarantees to Volkswagen for its projects in China, citing human rights violations in Xinjiang.

But Germany’s state investment guarantee portfolio has a long way to go in its push to diversify from authoritarian rivals: Latest official figures show that together, China and Russia make up 45 percent and 64 percent of Germany’s total guarantee portfolio by number and euro volume, respectively.

(Photo by Flickr/Jernej Furman)