THE BIG BLIND SPOT

California skips Econ 100

California seems to be ground zero for confusion over supply and demand: The state’s new budget, approved by Governor Newsom this week, suggests that California’s response to an era of shortage is to hamper production while encouraging consumption; in other words, depress supply and inflate demand.

- The state budget includes a tax on lithium, levied at a flat per-ton rate, to generate revenue for environmental protection work. Remember, here, that lithium is a critical input into new energy products like EV batteries. The move goes against warnings from lithium companies that it will hurt the sector and delay deliveries to EV makers, undermining the country’s battery and EV industries.

- The added irony: California simultaneously approved gas refunds for some 17.5 million taxpayers. Current sky-high gasoline prices are due to insufficient production and refining. A gas tax refund not only fails to address that fundamental problem, but also threatens to encourage consumption and therefore further to exacerbate shortage (and drive prices up).

- And: California intends to send some 23 million residents “inflation relief” stimulus checks. See above re inflating demand at a time of shortage. And this move comes despite the widespread acknowledgement that the federal government’s COVID-19 stimulus measures helped to fuel today’s inflationary trends by inflating demand.

Not brilliant.

CPI, 12-Month Percent Change

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSIs US manufacturing headed for a downturn?

Early, regional indicators suggest that US manufacturing may be facing a downturn – right when the country can least afford it. On June 28, the Richmond Fed announced that its composite index of manufacturing has fallen to its lowest level since peak pandemic in 2020. This comes close on the heels of similar readings from Fed banks in Dallas; Philadelphia; and Kansas City, Missouri. These gloomy indicators are not exactly a surprise: Factories are grappling with a perfect storm of supply shortage and exploding costs. But the consequences of manufacturing slowdown could still shock. Inflationary trends caused by upstream materials shortages are already wreaking havoc in the US economy. Now, those upstream material shortages risk translating to mid- and downstream shortages, a ripple effect that would compound today’s economic crisis – and to an extent that supply-unaware market leadership likely underestimates.

And it certainly doesn’t help that investment in manufacturing seems to be slowing down too. South Korean battery maker LG Energy Solutions said this week that it’s reassessing a planned 1.3 USD investment for an Arizona battery factory due to “unprecedented economic conditions and investment circumstances in the United States.” That is code for rising interest rates and inflation, as well as paralysis in Washington that threatens government support for the industry. And it’s just the latest indicator that inflation, economic uncertainty, and political dysfunction risk delaying much-needed investment in US industry – a delay that in turn risks aggravating inflation, economic uncertainty, and political dysfunction.

But don’t worry: Europe has it worse

Preliminary figures released Friday show Euro zone inflation at a record high of 8.6 percent year-on-year for June. Compare that to 8.1 percent in May – and predictions of 8.4 percent. And if the US has limited options to respond to its own inflationary trends, the EU’s is a whole other level of dilemma: Yes, the European Central Bank (ECB) could hike interest rates up à la Fed in a knee jerk reaction to inflation. But the resultant recession risk might be too much for the EU to swallow. The bloc’s economy is under enormous, and escalating, pressure from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A cold winter of energy shortage looms ahead. And shaky debt dynamics in the economically heterogeneous bloc mean that any disruption could send it into another debt crisis. (Plus, inflation can in fact soften the EU’s debt burden).

Lagarde hit hawkish notes this week: “If the inflation outlook does not improve, we will have sufficient information to move faster.” But the ECB definitely does not want to move faster; they are likely to do everything they can not to join the Fed’s aggressive tightening.

Sony, Honda, and the future of tech-auto tie-ups

A few weeks ago, Japanese electronics conglomerate Sony and carmaker Honda teamed up to form a 50-50 joint venture called Sony Honda Mobility to develop electric vehicles. This sort of tech-auto partnership has long been a staple in the Chinese industrial ecosystem. But the Sony-Honda joint venture suggests that it may soon become the norm internationally, too.

Technological advance, the rise of autonomy, and the EV transition mean that cars are increasingly becoming computers-on-wheels. Of course, not everyone is responding with tech-auto partnership. Some are trying to go at it alone. Mercedes-Benz now styles itself as a “luxury and tech company;” Apple is working on a secretive Apple Car. To be seen if the potential clunkiness of cooperation across industries is worth the expertise boon of combining forces.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSThe G7 announces moves toward a Russian oil price cap – and it doesn’t mean much

G7 leaders announced on Tuesday that they had agreed to explore imposing a price cap on Russian oil exports. This would constitute a ban on transporting Russian oil sold above a certain price; the idea is to shrink Putin’s war chest while keeping Russian oil flowing. The announcement seems more an indication of the degree to which G7 leaders’ hands are tief than of progress, in any direction: Still dependent on Russian energy, they’re trying, without actually doing anything, to make that reliance less beneficial to Moscow. How do they intend to implement this cap? What happens if Russia simply decides not to sell the oil? Or to route it to more friendly players like India and China. With a world desperate for energy, Russia, like it or not, is in the driver’s seat. The price cap talk is a case of beggars trying to be choosers, without addressing the real issue (read: supply) that has placed them in these dire straits.

Meanwhile, Moscow seems confident in its upper hand. For months, Japan has insisted that divesting from Sakhalin-2, its LNG joint venture with Russia, is not an option. That choice may now be forced upon Tokyo as Russia on Thursday created a new firm to seize full control of the oil and gas project. This gives the Kremlin authority to decree whether foreign partners, including Shell and Japan’s Mitsui and Mitsubishi, can stay – or be expelled with no compensation. For Japan, the loss of Sakhalin-2, which accounts for around 10 percent of the country’s LNG imports, comes amid a summer heatwave that’s already straining the national power grid. And there are diplomatic factors consider: if Tokyo opts to buy a stake in the Sakhalin-2’s new operating structure to safeguard its investments, that could divide the G7’s united front against Russia.

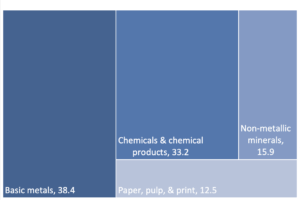

Germany’s chemicals conundrum

Germany’s huge industrial chemicals sector has long relied on cheap Russian natural gas for power and as feedstock. Now that dependence has become a critical vulnerability: Moscow has reduced supplies of gas and is threatening to turn off the taps altogether.

Without sufficient gas, chemicals companies would have to shut – a costly process, and one that would have ripple effects across global industry. This would disrupt supplies of ammonia and acetylene, inputs needed to make plastics, pharmaceuticals, and fertilizer, worsening supply chain snarls and aggravating the food crisis. And that is just the immediate chaos. This short term disruptive consequence of the Russia-Ukraine war could, in the longer term, lay the framework for a reshaped international industrial environment: Without sufficient energy supply in Germany, larger chemicals companies like BASF may look to move more production to China – which continues to purchase Russian oil and gas. Yes, that comes with geopolitical, regulatory, and quality concerns. But if the choice is energy or no energy, there’s only one way to go.

Copper prices are down, for now

Copper futures are down 13 percent this month, after nearly doubling since July 2020. This is being interpreted as a sign that global growth may be slowing, especially in China. But does that interpretation mistake blip for trend? The drop in prices is in large part a function of Beijing’s COVID zero policy and corresponding decline in Chinese manufacturing. Yet Beijing’s COVID zero policy seems to be easing, now – and, regardless, Beijing is hardly about to abandon its manufacturing ambitions in the longer term, especially in the emerging strategic industries dependent on copper. All of which is to say that yes, this is a useful reminder that the inexorable upward march of critical mineral and metal inputs might not be entirely inexorable. But at the same time, don’t expect the copper slide to last.

A new force in battery materials

Posco, South Korea’s largest steelmaker, is getting serious about a pivot to battery materials. A senior executive last month described China’s quest to sweep up lithium and other minerals worldwide as “literally war” — and it seems that Posco intends to fight. The company plans to invest 20 billion USD to secure stable supplies of key raw battery materials. It has already partnered with General Motors to develop a cathode plant in Canada, is working with Australian mining group Hancock Prospecting to develop mineral supplies, and just this week signed a deal to supply cathode and anode materials to UK electric vehicle start-up Britishvolt. Will we see more contenders emulating Posco’s globe-spanning, but China-shunning, supply chain across the battery production process?

(Photo by Pexels)