In upstream resources, US critical mineral capacity remains critically inadequate, China buys up Indonesia’s cobalt, and what are the prospects for made in USA uranium? Plus, US GDP grows, but that big picture figure belies pain under the surface, crumbling tech players, and stalled manufacturing. And, of course, a market bloodbath in China.

THE BIG BOTTLENECK

US critical mineral capacity is critically inadequate

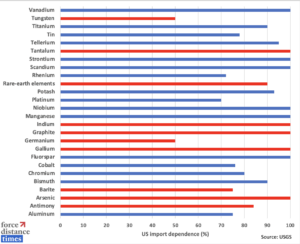

The 2022 US Geological Survey published data on 32 critical minerals. Of those, the US is more than 50 percent import dependent for 26, or 81.25 percent. And China is the top source of US imports for 11. This constitutes a dangerous vulnerability. Critical minerals are necessary, limited, and in many cases consolidated inputs into modern industry. And the US lacks domestic or trusted sources of many of them. Rare-earths are the well-worn example: Those are necessary inputs across defense and commercial applications; the US is 90 percent import dependent for rare-earths and sources 78 percent of its imports from China. But rare-earths are just one case. Take graphite, a critical material for battery production. The US is 100 percent import dependent for graphite – and China controls some 82 percent of the market.

Critical minerals for which US import dependence is at least 50%

Source: USGS

The consequences of this dependence are poised only to grow. Look, for example, at today’s energy transition. According to the International Energy Agency’s latest annual World Energy Outlook report, global fossil fuel use is set to peak in just a few years – in large part as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which the IEA’s executive director has called the “first truly global energy crisis.” But China dominates the mining and processing of many key minerals that clean energy technologies require (and also controls vast market shares in the manufacturing of solar panels, wind turbines, EVs, and batteries).

What happens to US, and global, energy security in a world where Beijing controls the critical materials on which energy production – and modern industry – depend? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is making painfully clear the danger of relying on an adversary for resources. If the US doesn’t resolve its critical mineral problem, it risks cementing reliance, and greater reliance, on a different, more dangerous adversary.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSMade in USA uranium

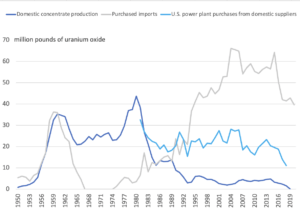

Critical dependencies also lurk in nuclear power, which in recent months has enjoyed renewed interest as an alternative fuel source that could help make the clean energy transition more feasible. But for uranium to be a secure and sustainable energy source, the US needs quickly to ramp up production.

Accordingly, the Department of Energy said this week that it’s working on a domestic strategy to source domestic uranium for nuclear reactors. That’s a good start: domestic production peaked in 1980, dropping precipitously since; the US is currently 95 percent import-dependent for uranium to power its nuclear plants, with 35 and 14 percent of those imports coming from Kazakhstan and Russia, respectively. And even those figures belie the extent of the dependence of US nuclear energy dependence on Russia: The US is currently developing a new generation of small nuclear plants, and Russia has a full monopoly on the global supplies of the high assay low enriched uranium (HALEU) the reactors need.

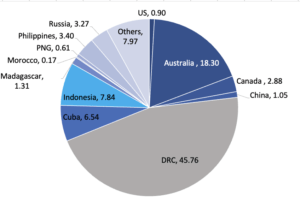

Indonesia could become a major cobalt producer

Indonesia already accounts for 37 percent of global nickel production. Now, a forecast by Benchmark Mineral shows that the Southeast Asian country could increase its cobalt production thirty-fold this decade and become the world’s second-largest producer of the battery mineral, after the Democratic Republic of Congo – in large part due to Chinese investment. Indonesia has the world’s third-largest cobalt reserves, but so far has limited mine production of the mineral.

This will make Indonesia a newly significant player in the global cobalt market and could help plug the global supply shortfall. But it won’t diversify the cobalt value chain away from Chinese control. These new developments in Indonesia are primarily a function of Chinese investment. For example, one of the projects is PT Huayue, a joint venture on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi established by Tsingshan Holding Group and China Molybdenum Co. That project shipped its first batch of mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP), a product used to be processed into nickel and cobalt chemicals for EV batteries, in February.

One potential wildcard here: The US Inflation Reduction Act includes prohibitions on the use of inputs from Chinese firms as “foreign entities of concern.” This could restrict US access to Indonesian cobalt – but perhaps also incentivize non-Chinese-invested production elsewhere.

The UK reinstates its fracking ban

On Wednesday, the new British prime minister Rishi Sunak reversed his predecessor Liz Truss’s lifting of a ban on fracking for shale gas. Truss ended the ban, in place since 2019, in the hopes of strengthening the UK’s energy security. (Though it’s unclear how much the moratorium would have boosted the UK’s energy supplies.) Sunak’s reinstatement of the ban seems counterintuitive in the midst of an energy crisis. It raises the question of what measures the new UK government will take to shore up new production as Europe faces an unprecedented squeeze.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSBig picture, US GDP grows

The US economy grew by an annual rate of 2.6 percent in the third quarter – more than the 2.3 percent economists had predicted, and ending a two-quarter streak of negative growth. That’s the glass half full interpretation. The glass half empty version would point out that underneath this big picture, more granular, potentially leading indicators point to a cooling economy with high recession risks: Home sales have tumbled, for example, and 30-year mortgage rates just breached 7 percent. Plus, tech firms – the players that have fueled much of the past years’ economic windfalls – are in free fall (see below).

Bits bite the dust while atoms rise

This week saw a series of disappointing earnings reports from tech firms – and with them a lot of red in US capital markets: Amazon stock plunged 13 percent in extended trading on Thursday after the retailer missed revenue estimates and predicted slower Q4 holiday sales; Alphabet reported a steep drop in profits; Meta profits halved; and Microsoft predicted a slowdown in cloud computing growth. And this just adds to an already disastrous picture: The largest tech stocks have lost a collective 3 trillion USD in stock market capitalization over the last year.

While those bit-based giants plummet, atoms are stepping up. ExxonMobile’s Q3 results far exceeded expectations: The company reported a record-breaking quarterly profit of some 20 billion USD, 4 billion more than forecast and almost tying Apple’s earnings. Nor is Exxon alone. Chevron reported a quarterly profit of 11.2 billion USD, its second-highest ever.

All while US manufacturing stalls

S&P Global PMI data, released October 24, showed a near-stalled US manufacturing sector. The preliminary S&P Global US Manufacturing PMI fell to 49.9 from 52 in September, well below expectations of 51.2. The decline in US manufacturing activity is expected only to accelerate in the months ahead: The bulk of current production is being undertaken by firms addressing backlogs of old orders, rather than new ones.

The drop appears to be a function of two interrelated trends. First, new orders are shrinking: Manufacturers registered lower demand as the effects of high inflation and stockpiling kicked in. Second, a strengthening dollar has made US exports less competitive, forcing the sharpest decline in export demand since May 2020.

The Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) measures the activity level of purchasing managers in the manufacturing sector. Readings above 50 indicate expansion in the sector; below 50 indicate contraction.

German manufacturing sags, and its China exposure rises

Faring even worse is Germany. S&P’s PMI for the country slumped to a 29-month low of 44.1 from 45.7 in September, as high energy costs continued to crimp manufacturing. The chemicals giant BASF is a case in point: The company said it will downsize “as quickly as possible and permanently” in Europe and shifting production elsewhere – including China, where it has just opened 10 billion euro (9.97 USD) plastics engineering facility, despite the past year’s primer in avoiding dependence on geopolitical adversaries.

And Germany is increasing its reliance on and exposure to China elsewhere, too: The cabinet approved a compromise to sell a 24.9 percent stake in a Hamburg port terminal to Chinese shipping giant Cosco, and may reportedly greenlight the sale of a domestic chip factory to a Chinese company as early as next week.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSChina’s market bloodbath

Global investors dumped Chinese equities en masse this week following the Chinese Communist Party’s confirmation of Xi Jinping’s third term in power, and the promotion of his key allies and proteges to the 24-member politburo.

The frantic sell-off reflects fears that Beijing will continue enforcing policies that crimp economic growth and hurt investors’ portfolios. International investors pulled a record 2.5 billion USD from mainland stocks on Monday alone, the Nasdaq Golden Dragon Index ended the week down over 12 percent since before the party congress started, and the Hang Seng Index has erased all its gains since April 2009. If it wasn’t clear before this week, it should be now: Investing in China is a game of political roulette; returns are driven not by market fundamentals but by ideological whims.

Amid China’s market rout, however, one important indicator is booming: Chinese exports to Russia, which increased 21.2 percent in September– the third consecutive month of double-digit growth, and considerably faster than China’s overall export growth of 5.7 percent.

(Photos by Tom Fisk, Skitterphoto/Pexels)