OPEC+’s production cuts are an explicit, deliberate snub to Washington and the West, showing that productive beats consumptive power. Also not brilliant: US monetary tightening is cooling the economy, but in all the wrong places – and that ups recession risks. Plus: Maize malaise in Europe, the Mississippi’s dry spell, a US industrial policy stumble in lithium, and plunging global FX reserves.

THE BIG CUT

OPEC+ has some cutting messages for the West

Moscow is playing with the Nord Stream pipeline as its own personal yo-yo: In late July, Russia resumed flows at reduced levels in an apparent concession to Europe – only to halve deliveries again just days later. Then, last week, Moscow announced a full, three-day shutdown of the Nord Stream pipeline to start August 31, ostensibly for “maintenance.” This turbulence and uncertainty have sent European natural gas futures soaring to their highest level since 2008. And the pain is expected to last. The UK regulator has raised the energy price cap – the max that energy companies can charge households for every unit of energy – by 80 percent. The Belgian premier warned this week that Europe faces a decade of tough winters ahead. (Compounding the problem, in oil, the Russia-backed Caspian Pipeline Consortium confirmed on Tuesday that Russian and Kazakh oil exports via its Black Sea terminal will face at least a month’s disruption each due to repairs – another hit to European energy imports.)

OPEC+, the oil-exporting cartel led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, announced this week that it will slash output by 2 million barrels of oil per day – about 2 percent of global supply – in the midst of a global energy crisis. The deep and abrupt cut, at a time when Brent crude is still hovering around the 90 USD range, is all but sure to push up oil prices, keep inflation higher for longer, and force central banks to stick with rate hikes.

There are two silver linings, however, both of which add up to this cut meaning less, in terms of production, in reality than paper figures might suggest. First, because of OPEC+’s chronic underproduction, the real cut will be smaller and less than half the official curb. Second, even without the OPEC+ cut, Saudi Arabia and Russia — the world’s second- and third-largest crude producers — would likely have seen output fall in coming months anyway. That’s because Saudi Arabia has never pumped above 11 million barrels per day for more than a month or two, while sanctions on Russia are hobbling its ability to maintain current production levels.

That said, the geopolitical and political context of the OPEC+ decision lend it outsized significance. This cut is an explicit snub to Washington and the West. It comes just months after President Joe Biden’s visit to Saudi Arabia, which was intended at least in part to encourage production hikes. It undermines the latest price cap plans for Russian oil agreed to by the G7 and EU. And it constitutes an unmistakable show of support for Putin, whose war machine will be greased by higher oil prices. Plus, US mid-terms are a matter of weeks away: This is not a great look for Biden heading into them.

More broadly, the OPEC+ move underscores the degree to which international rule-setting and consumptive power might be overestimated – and productive power underestimated. OPEC+, as an oil producer, is loath to have oil consumers influence global oil prices, as with moves like the US SPR release and the price cap plans. Accordingly, OPEC+ is showing that it’s in the catbird seat, Western rule-setting influence notwithstanding. Time, perhaps, for the US to try boosting its leverage by increasing domestic production?

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSIn US jobs, it’s (still) too damn hot…

Two data points this week suggest that the Fed’s battle against inflation is showing results — but in all the wrong places, and in a way that increases the recession threat.

First, jobs: The US economy added 253,000 jobs in September. Unemployment is at a half-century low. This would be good news in a normal economic environment. But today’s is anything but. The Fed is almost certain to read these job figures as indication that the labor market is still too hot, and not a Goldilockian “just right.” Markets noticed: The Dow fell over 600 points on Friday, the Nasdaq slid 3.8 percent, and the S&P 500 lost 2.8 percent.

One wrinkle: The number of new job openings in the US plunged by over a million in August from the previous month. It’s the steepest drop in nearly two and a half years. That could mean that relaxation of the labor market is on the horizon, with it a slowdown in monetary tightening. But job opening data is a tough one to read – and a still-low layoff rate cautions against reading too much into the indicator.

…while manufacturing cools: Not brilliant

The second data point is manufacturing: US factory activity grew at its slowest pace in September since May 2020, according to an Institute for Supply Management (ISM) survey. The PMI for September came in at 50.9, versus 52.8 in August – apparently a function of dwindling demand as the effects of monetary tightening hit. That reality is evident even in the hot industrial sectors that for the past years have been synonymous with shortage: Samsung’s operating profit sank 32 percent this quarter as the tech downturn depressed demand.

This is a worrying development. It suggests that the Fed’s rate raising is succeeding in cooling the very parts of the economy that need more heat (read: manufacturing) – but not those driving the hiking calculus (read: labor). Today’s inflationary trends are in large part a function of industrial shortage. The high-level, if difficult, answer to solving them without sparking recession is to raise supply to meet demand. But it seems that US monetary policy is instead encouraging demand to drop to meet supply, a reality that fails to address the fundamental economic imbalance and, if taken to its logical conclusion, ends in recession. Plus, with the labor market still tight, the Fed is unlikely to correct course.

Global FX reserves are plunging

Bloomberg data show that global foreign currency reserves are falling at their fastest pace ever. This year, reserves shrank by 1 trillion USD, or 7.8 percent, to 12 trillion USD. That’s the biggest drop since 2003, when Bloomberg began compiling the data.

Partly, the slump is due to the strong dollar, which has pushed down other reserve currencies like the yen and euro, reducing the dollar value of holding those currencies. Another related and perhaps more worrying reason: Central banks are being forced to draw from their FX coffers to defend their own currencies. India, Japan, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong, and others have all had to intervene to fend off depreciation.

With the US Fed continuing to hike rates, strengthening the dollar, other countries will increasingly depend on their reserves to enable interventions. For emerging markets, this can be a daunting prospect: Depleted reserves imply insufficient funds for critical imports of food and energy – at a time when those are already in short supply.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSAn illustrative lithium stumble

A public-private US lithium project has fallen through. This week, Reuters reported that the US Department of Energy has rescinded a 14.9 USD million grant it had awarded to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway for a pilot project to filter lithium from superhot geothermal brines, which if successful would represent a new way of producing the critical mineral.

Several factors may have sunk the project. There were technical challenges of using a commercially unproven process to extract lithium from hot brine, then developing new technology to process that material into lithium hydroxide. There were also business challenges, as negotiations reportedly stalled over questions of patents, changes to technology, and whether Berkshire could eventually sell the lithium business despite government involvement in building it.

The takeaway from this episode: The US has recognized that today’s industrial revolution calls for industrial policy. It hasn’t figured out what American industrial policy entails – or how to operationalize it. Expect a host of stumbles ahead as both government and private sector struggle to find ways of aligning efforts.

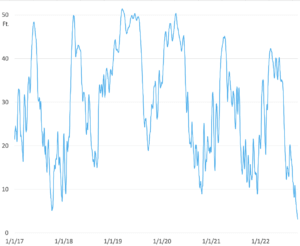

The Mississippi River dries up

The Mississippi River, one of America’s busiest waterways, is seeing near-record-low water levels after a particularly dry summer — not unlike what ailed the Rhine and Danube in Europe this summer. That’s snarling barge traffic: The US Coast Guard reported at least eight barge “groundings” this week. Shippers who rely on the river to transport grains, fertilizer, metals, and petroleum are now backed up and stuck in bottlenecks, causing long lines of trucks at loading facilities, and adding new inflationary pressure to the economy.

Nor is this only a problem of supply chains and inflation. There are public health implications, too. As the river’s freshwater outflow dwindles, saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico is creeping in upstream, which risks endangering drinking water supplies drawn from the north. The US Army Corps of Engineers is now working to construct an underwater sill to slow the flow of saltwater and keep salt levels from rising too much.

Mississippi River water level at Vicksburg, Mississippi

Europe faces maize malaise

The EU’s maize (or corn) harvest is expected to hit a 15-year low, thanks to this summer’s heatwaves and drought. The Agricultural Market Information System, created by G20 agricultural ministers, forecast this year’s crop is forecast to come in at 57.5 million tonnes. That’s a tick above the EU’s own prediction of 55.5 million tonnes. Particularly hard hit are major producers including Romania and France, with the latter forecasting a three-decade low crop size. The damaged crop mean imports are expected to hit a four-year high. It also means the EU is now set to be even more reliant on Ukraine for the grain — right as the UN-brokered Black Sea export deal faces an uncertain future beyond its November expiry date.

Remember that the real consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for the global food supply have fully to hit. And those consequences are only going to be compounded by exogenous strains, like those of extreme weather events.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSThe UK’s about-face

“We get it, and we have listened,” said UK prime minister Liz Truss and her chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng on Monday as they made a humiliating U-turn, reversing a cut to the top income tax rate. The backtracking suggests Truss has lost, or is quickly losing, control of her party. That will deepen her crisis of governance: even loyal backers now openly question her mandate.

For now, Truss and Kwarteng’s attempts to course-correct have repaired some of the damage: The pound has recovered to a rate higher than before the tax plans were unveiled, while yields on the 10-year gilt slid slightly, but still far exceed those from before the mini-budget. Next up, investors will be looking out for Kwarteng’s medium-term fiscal plan to cut UK debt, which he is expected to deliver later this month.

Brazil’s cliffhanger continues

The presidential election in the world’s fourth-largest democracy, Brazil, was too close to call: The incumbent, far-right Jair Bolsonaro, notched 43.2 percent of the vote to his leftist challenger Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s 48.4 percent. A run-off is now scheduled for October 30; Bolsonaro will need to garner millions more votes to win outright. Things could get messy. Pro-Bolsonaro pundits are baselessly claiming widespread voter fraud, and Bolsonaro has said that there are only three possible futures for him: Arrest, death, or victory.

Bolsonaro’s stronger-than-expected performance appeared to boost Brazilian markets this week. That’s likely a function of investors expecting that Lula will respond to his adversary’s better-than-expected performance by pivoting towards the center with more market-friendly policies.

(Photo source: Saudi Press)