Supply Side Economic Risks — But Demand Side Solutions

If inflation was the big word last week, this week it’s recession. Mark Zandi, Moody’s chief economist and a favorite source for the Biden administration, warned on Tuesday that he sees a 35 percent probability of the US entering a recession in the next two years; Goldman Sachs has projected the same. Who knows how much weight is to be put in those figures: If the past years have made anything clear, it is that tomorrow is impossible to predict, let alone two years from now. But the discussion of recession risks underscores a critical weakness in US monetary policy, and industrial policy more broadly. The Fed’s Jerome Powell has said his goal is to “get inflation down without a recession.” But the tools at his disposal are all demand side (e.g., adjusting interest rates to reduce demand) when what the US really needs is supply. The forces creating inflation, and with them recession risk, are all matters of supply – of labor, houses, semiconductors, critical minerals, perhaps soon food. To address those, the US would have to invest in production of critical inputs, manufacturing facilities, and improved logistics systems. And that is not a set of tools at the command of the Federal Reserve.

Is Streaming Dead?

Netflix is having a rough week: Shares fell more than 35 percent on Wednesday after the company reported having lost some 200,000 subscribers this quarter. Other streaming stocks – including Paramount Global, Spotify Technology, and Walt Destiney Co. — followed. This, combined with the shuttering of CNN+, has prompted a host of eulogies to the streaming era, just two years after global pandemic made the industry a market darling. There is one data point that seems to be missing, though, in this doom and gloom: Netflix may have lost subscribers this quarter, but its profit was up (if by a small margin: 0.6%) and its revenue way up (9.83%). Is it possible that the markets are asking the wrong questions? Subscriber growth can’t less forever. A profitable business model can.

Regardless, the other wrinkle to add here is that of TikTok: Netflix subscribers are down. So is Facebook engagement. But TikTok engagement continues to climb, and at pace. Users reportedly spend an average of nearly 36 hours a month on the app, up from about 22 in 2020. Is this a challenger to the streaming model — or an approach to content delivery and targeting that the major streaming platforms can emulate?

Failed in New York? Try Zurich.

With US capital markets increasingly difficult for Chinese companies to enter and navigate, China appears to be turning to Europe. In February, Chinese regulators expanded its Shanghai-London stock exchange link to include Germany, Switzerland, and Shenzhen, in an attempt to attract more foreign firms to list in China. And Chinese companies are taking advantage: In the past month, three Chinese lithium battery makers have announced that they are looking to list on the Swiss exchange. That’s in addition to a heavy machinery maker and medical equipment manufacturer that have already unveiled plans to sell shares in Switzerland. This bid for offshore listing opportunities in Europe comes as Chinese firms face a mass delisting from the US. Didi is set to vote next month on whether to delist from New York, while investors have sped up shifting their JD and Alibaba shares from the US to Hong Kong.

The potential of a mass migration to European exchanges underscores the inadequacies of US policies aimed to impose costs on Chinese companies. Those don’t work if they’re unilateral; if China can simply turn to allied and partnered markets. At the same time, there’s also a one-sidedness to the European listings that could indicate a vulnerability in Beijing’s efforts fully to integrate into the global financial system: The China-Europe stock exchange link is intended to be a bi-directional one. But no European company is interested, for reasons including potential legal risks to its executives, disclosure requirements, and China’s implicit support for Russia, not to mention Beijing’s regulatory opacity.

An IP Snag in the US-South Korea Battery Alliance

US automakers including General Motors and Ford have formed partnerships with South Korea’s top three battery makers LG, SK, and Samsung in a push to expand EV productions. But the Korean companies are expressing worries about the security of their technological know-how, Nikkei reports, as their American partners push for sharing arrangements while at the same time also ramping up efforts to produce their own batteries. This underscores both the difficulties of so-called “allied shoring;” joint efforts to build robust supply chains. It also underscores the difficulties ahead for US-specific efforts to develop a functioning domestic EV industry. Regardless, if US carmakers wants to make progress on their EV ambitions and continue developing alliances with South Korean firms, they will have to reassure the Korean battery makers of the safety of their trade secrets.

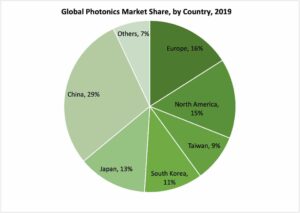

The Dutch Bet Big on Photonics

In March 2020, the EU identified six key enabling technologies as critical to the bloc’s industrial transformation: micro and nanoelectronics, nanotechnology, industrial biotechnology, advanced materials, advanced manufacturing technologies, and photonics. Now, the Netherlands is taking the lead with the latter. Photonics is the technology of light used in everything from communications infrastructure and sensors to biomedical sciences and advanced manufacturing. This month, the Netherlands announced a €1.1 billion investment in next generation photonic technology, with €471 million coming from the government and the rest from universities and private partners. The initiative, run by the government-backed agency PhotonDelta, will aim to build a national photonic chip champion much like ASML, which is of key strategic importance to Europe as the dominant player in in advanced extreme ultraviolet lithography. The large investment, which PhotonDelta’s CEO called a “gamechanger,” is the latest example of Europe’s bent for industrial policy trying to keep up with a new industrial revolution.

(Photo by Pexels)