FACTORS: As agricultural input prices swell, producers struggle to keep up

Fertilizer prices fell 30 percent on Thursday – after having skyrocketed by 133 percent over the past year. But the plummet does not indicate that the global fertilizer shortage has been resolved. Rather, the price drop is a function of demand destruction: Fertilizer is simply too expensive. Buyers cannot pay the record high prices that characterized April and May.

This is just one element in a larger story of swelling agricultural input prices that risk creating ripple effects in an already-reeling industry. A recent report from Texas A&M University’s Agricultural and Food Policy Center projects large-scale decreases in farm income as a result of rising costs for crops and inputs. Further bearing out the point, and compounding the problem, US cattle ranchers are in the process of shrinking their herds as feed and other costs pile up: Beef production in 2023 is expected to drop by 7 percent, amid an already inflated market, and cattle prices to hit record highs. In other words: Shortage and inflation do not just mean that the food being sold today is more expensive than it was yesterday. They also mean that tomorrow’s food will be more expensive to produce than was yesterday’s – and therefore that less of it will be.

Share of global trade, in calories, impacted by export restrictions across global crises

Source: IFPRI

And the (very expensive) cherry on the top: In response to fears about food supply, food protectionism continues to grow, further limiting global access. This week, India, the world’s second largest sugar exporter, announced it will be capping exports of the commodity through September – after last week announcing a wheat export ban.

FACTORS: Manufacturers search for gas money

US crude oil has climbed to its highest level in over 11 weeks – right as Memorial Day weekend kicks off the season of summer travel. The average price of regular unleaded gasoline in the United States is currently sitting at 4.60 USD/gallon, a record. No one is optimistic. The entire energy industry, from coal to natural gas to oil, faces tight inventory even as demand threatens to grow. As S&P Global’s Daniel Yergin put it, clearly, this week, “you have to assume that things will get worse.”

But if the effects of high prices are, for the moment, being felt most directly at the pump, the longer-term consequences risk being even more disruptive: All global industry depends on reliable and affordable energy – and without industry operating at full capacity, shortages and price increases will only worsen. Manufacturers are worried and trying to respond. For example, BMW is reportedly looking at new investments in solar, geothermal, and hydrogen energy to cut its dependence on natural gas (Germany still relies on Russia for 35 percent of its natural gas needs), which last year fueled 54 percent of the German carmaker’s energy consumption.

FACTORS: The labor crisis isn’t over

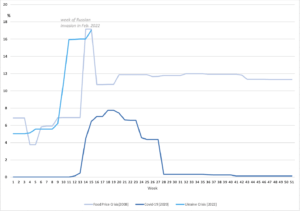

Physical resources are not the only factors in short supply: The global economy is also facing a dearth of labor. The latest figures from the International Labour Organization indicate that global hours worked are still below pre-COVID-19 levels. In part, this is a function of the pandemic induced disruptions to labor markets (e.g., demands of childcare, limitations on migration, new models of consumption) that made labor shortage a dinner table conversation in the United States last summer. But now, emerging political and geopolitical stressors are compounding the problem: China’s recent pandemic lockdowns accounted for 86 percent of the decline in global hours worked in Q1 2022; thanks to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, hours worked in both countries have collapsed.

Looking forward, brewing international food crisis risks causing widespread malnutrition and hunger, further shrinking the labor pool. Inadequate training and education as a result of COVID-19 could add to the problem. In short, sub-optimal labor levels are already compounding supply chain disruptions and inflationary pressures. And the shortage risks continuing – at least to some extent – into the coming years.

MARKETS: With inflation settling in, the consumer asks for less

According to a May survey, some 80 percent of Americans report that they intend to cut down their spending in the months ahead. That could transform the US retail industry. Budget is in: This week, Dollar Tree and Dollar General reported first quarter earnings that far exceeded Wall Street’s expectations, and saw their shares jump by 21.87 and 13.71 percent respectively on Thursday in response. And budget applies to what people are buying as well as where they’re buying it: Walmart reported better-than-expected, and growing, sales in the first quarter, but also a drop in revenue as customers switched from big-ticket and brand name items to generic, discount, and lower-margin products. Already, retailers are responding to the trend: Walmart is stocking more half gallons of milk so shoppers don’t have to spring for a full gallon; Procter & Gamble has advertised a dish-soap bottle that ensures users can extract every drop; across the board, stores are introducing more bargains, cheaper store brands, and rewards programs. All of this adds up to both potential disruption and opportunity for the retail industry. Customers have spending power. But they’re anxious. They are therefore likely to keep buying, and perhaps even a good deal — yet with a restriction mindset.

MARKETS: Is Sri Lanka’s default just the first domino?

On May 19, Sri Lanka defaulted on its debt for the first time in the nation’s history as the government struggles to respond to an economic meltdown, complete with ballooning inflation, that has catalyzed mass social upheaval. Needless to say, this default could cripple the Sri Lankan economy. And the implications of this default could extend well beyond Sri Lanka itself: The country’s current economic situation parallels that of other lower-income nations; it risks being representative of a larger trend. During the COVID-19 crisis, Sri Lanka and other similar countries accumulated massive debt. Now, with interest rates rising, those debts are heavier – just as geopolitical crisis and global inflation make food and energy more expensive. It’s a dilemma not unlike that facing the American consumer, but at an international level and with consequences that could send ripple effects throughout an already tumultuous global economy.

Plus, the wildcard: Sri Lanka’s default – and the potential of others like it – could open the door to China. Chinese lenders hold the majority of external debt of low-income countries. Beijing could use global debt crisis to increase its influence over creditor countries and their natural resources. It could also use the meltdown to increase its say in the international economic architecture.

MARKETS: The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework ushers in an era of…more agreements?

On Monday, the Biden administration announced the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework – a new trade initiative with a dozen Asian partners including Australia, Japan, and Korea, framed around counterbalancing China’s dominant role in the region. The framework is neither a security pact nor a free trade agreement. It is a sweeping plan intended to shape international rules on the digital economy, supply chains, the environment, and labor; in the process to tackle inflation and expand US “economic leadership” in the region. In other words, the framework is detail, and commitment, lite. As it currently exists, it seems an agreement for the sake of an agreement.

However, other, parallel agreements have more meet to them: President Biden’s visit to Asia this week appears to have catalyzed a series of private sector-led industrial partnerships that could, from the ground up, help shore up supply chains and industrial capacity. Hyundai announced during Biden’s trip that it will invest over 10 billion USD into the US from now till 2025, with half of that funding EV and battery facilities in Georgia and another half fund efforts to strengthen US partnerships on advanced technology. Shortly thereafter Samsung SDI committed to partner with Stellantis to build the automaker’s first EV battery plant in the US.

MARKETS: The private sector thinks bigger is better. Does the White House?

This week, Harvard economist and former Obama adviser Larry Summers warned in a pointed tweet that overly aggressive and “populist antitrust policy” could make the US economy “more inflationary and less resilient.” The message sent shockwaves through the Biden administration – caught between commitment to anti-trust and its commitment to Summers’s advice.

But regardless of what the White House thinks, Summers and industry seem to be on the same page. This week has seen a series of high-profile integration announcements in Europe and North America framed around resilience and international competitiveness:

- Semiconductor giant Broadcom and cloud computing firm VMWare have reached a 60 billion USD deal that could be one of the biggest takeovers this year — if US authorities allow it to go through.

- German car and truck manufacturer Daimler is taking a roughly 10 percent stake in Germany engineering firm Manz to collaborate on battery production. The deal is still pending authorities’ approval, but the premise is clear: Manz produces machines needed for making batteries, and Daimler needs batteries for its EVs. The two firms will also share expertise to set up a pilot production line for lithium-ion batteries.

- Gamesa, the world’s largest offshore wind turbine company has been buffeted by rising energy and materials costs and project delays driven by supply chain disruptions. Now its majority owner, Siemens Energy, wants to claim 100 percent ownership, acquiring the remaining 33 percent of Gamesa with an offer of 4 billion euros. Siemens Energy’s CEO says the integration will help efficiency and increase pricing power in procurement.

MARKETS: ESSG stands for environmental, social, corporate governance – and sanctioned

China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), has earned itself a spot on two of Hang Seng’s ESG-focused indexes. That’s despite it being sanctioned by the United States – on the Department of Commerce’s Entity List and the Treasury Department’s non-specially designated nationals Chinese military-industrial complex list (Non-SDN CMIC).

The oddity of having a sanctioned firm in an ESG index illustrates the regulatory complications that Hong Kong financial institutions can face when dealing with US sanctioned entities. It also reflects the inconsistencies between different ESG rating methods. (See, for example, Elon Musk’s ire over Tesla’s exclusion from S&P’s ESG list.) More broadly, it underscores the inadequacy of US government measures like sanctions in an era of international financial markets.

(Photo by Pexels)