Is GDP a good measure of the US-China competitive balance? Meanwhile, oil climbs, firms scramble for a copper mine in Botswana, and investments pick up in integrated photonics. Plus: US military ambitions for an expanded AI fleet—and questions about the national industrial base needed for the build out.

THE US-CHINA GDP RACE

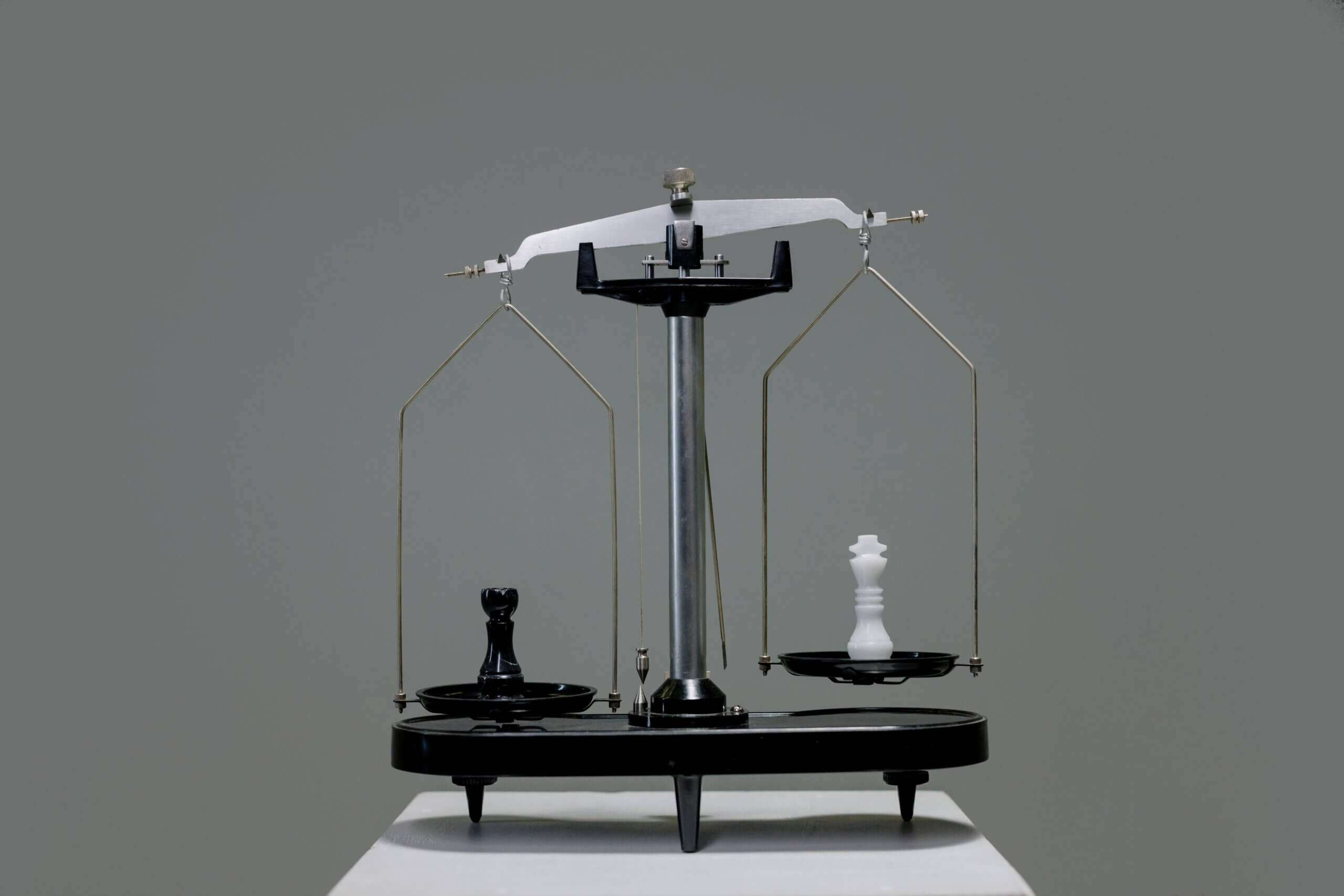

Symmetric measures aren’t great gauges of asymmetric competition

Bloomberg Economics has a new projection for China’s long-term economic outlook: growth in China’s gross domestic product is slowing more and earlier than expected. That means the country is “no longer set to eclipse the US as the world’s biggest economy soon,” Bloomberg writes.

But the absolute size of their respective national economies is only one facet of the US-China great power face off. Given Beijing’s tradition of using asymmetric strategies in its approach to geo-economic competition, it would be a mistake to directly equate China’s slowing growth with any blunting of the threat it poses to the existing liberal world order.

Beijing’s recent export restrictions on gallium (and germanium) are a case in point. China accounts for about 80% of global gallium production, giving it immense leverage over foreign chipmakers.

That’s not all. China is also eyeing gallium as a critical input to next-generation technologies like gallium nitride (GaN) semiconductors and indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) lasers. Beijing is betting that gaining dominance over key optoelectronic and microelectronic materials, and the emerging technologies that they power, will help propel it beyond legacy incumbents.

As China’s national advisory committee on the new materials industry put it recently: China should use an asymmetric strategy to tackle “chokehold” inputs and technologies. Of course, it helps to have a growing national economy to support R&D work. But the thing about asymmetric competition is that one can punch up, hard, even from a position of relative weakness.

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSOil’s rally fuels volatility

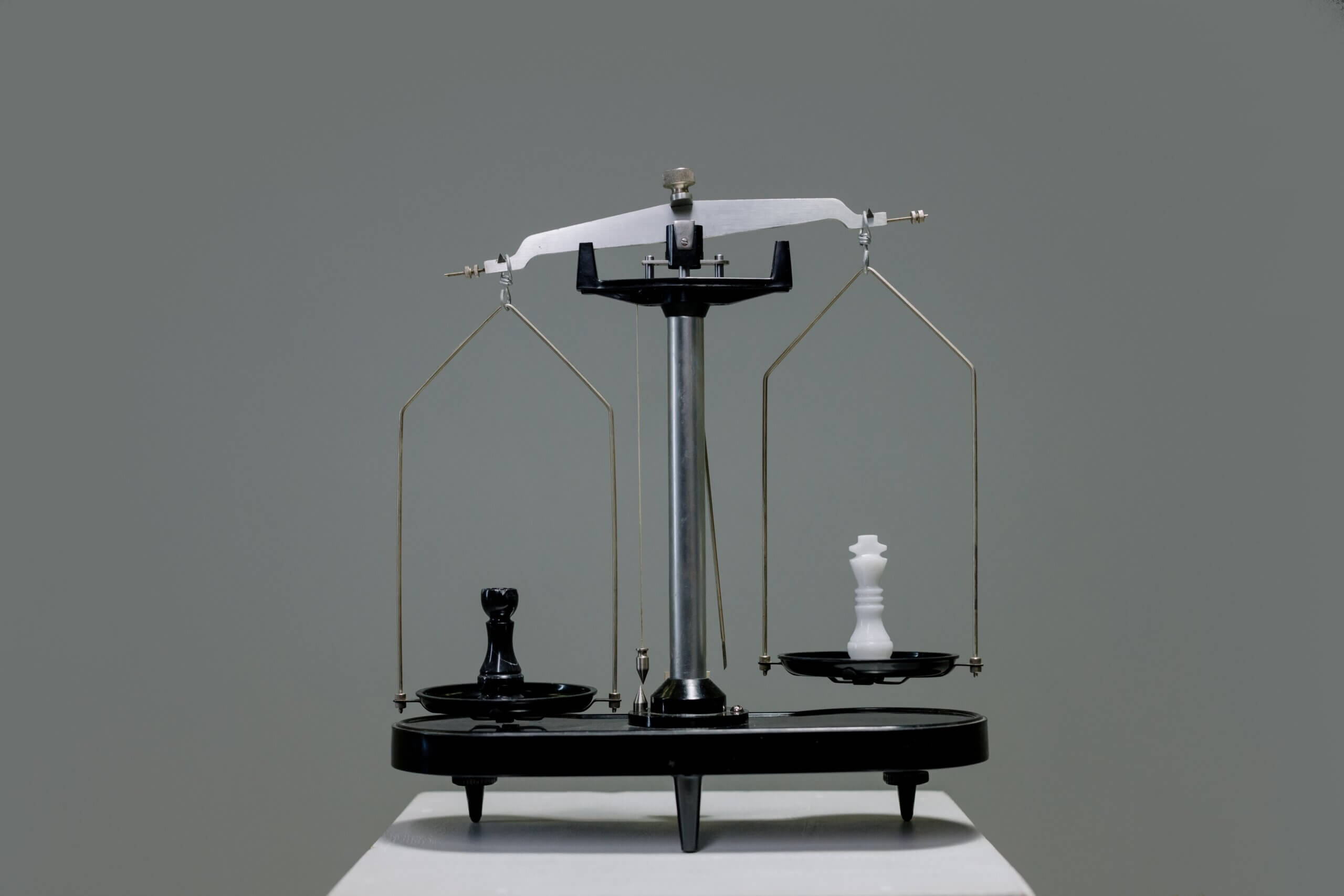

Oil prices rallied this week after Saudi Arabia and Russia extended their voluntary production cuts through the end of the year. The Brent benchmark soared past 90 USD per barrel before easing a smidge below that level on Thursday.

One consequence of the production cuts and subsequent rally is a tightening crack spread—that is, shrinking profit margins that refiners can earn from buying crude and turning it into gasoline and diesel. That’s discoursing refiners from stepping up capacity and investment, in turn making fuels more vulnerable to sudden swings.

Brent oil futures, August-September 2023

Source: Investing.com

Copper fever

Miners are scrambling to acquire a Botswana copper mine. Among them are three Chinese firms: Zijin Mining, MMG (whose parent is state-owned China Minmetals), and Aluminium Corp. of China (Chinalco).

The trio will be bidding against three South African suitors, as competition over one of Africa’s largest copper deposit heats up. Zijin and MMG already have significant copper portfolios; the former is planning a multi-billion dollar expansion to its Serbian copper mine.

Elsewhere, China’s CMOC Group said it will raise its copper output in the Democratic Republic of Congo to 600,000 tons next year, more than doubling 2022 levels.

It’s a whole new energy world

Who are the biggest, private energy players in China? According to new rankings from Hurun Research Institute, they are overwhelmingly in renewable energy (or “new energy,” as China calls it): battery giant CATL, EV makers BYD and Li Auto, solar modules manufacturer Longi, and solar power inverter maker Sungrow come in the top five.

Of course, “private” is often an ambiguous term for Chinese companies, given the size of state subsidies they receive—and that have enabled them to reach the scale that they command.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSTSMC—and everyone else—is betting on photonics

Chipmaking giant TSMC is investing heavily in silicon photonics, an emerging technology combining silicon chips with optic technology to boost chip performance for computing-intensive applications like AI. Legacy chipmaking and computing players like Intel, Cisco, and IBM long been developing silicon photonics solutions.

China, too, is pouring money into photonics. Look at Huawei: its venture arm has invested in a firm that makes indium phosphide (InP), a compound semiconductor and a key integrated-photonics platform. Meanwhile, over in Europe, Dutch VC PhotonVentures is raising a 100 million euro (107 million USD) fund to invest in photonic chip startups.

The US manufacturing slowdown drags on

US factory activity has contracted ten months straight, with August’s purchasing managers index from the Institute for Supply Management hitting 47.6—a slight improvement from July’s 46.4 but still far below the 50-point mark separating contraction from expansion.

Reuters notes that industrial electricity use and distillate fuel oil consumption have fallen less than would be expected from such a prolonged industrial activity downturn. Coupled with low levels of spare generating capacity and distillate inventories, this “[implies] the energy system is operating close to its maximum capacity.” That in turn risks resurgent inflation when the business cycle picks up again.

US manufacturing PMI

Source: ISM

The Pentagon’s AI fleet ambitions

The US Defense Department announced that it will invest hundreds of millions of dollars to produce thousands of air-, land- and sea-based artificial-intelligence systems in a bid to keep pace with China’s military advances.

But: does the US have a sufficient industrial base to ensure production of these cutting-edge autonomous systems? The high-tech applications depend on an array of critical upstream inputs: think chips and communication modules, specialty metal alloys, sensors, and the like. If Starlink’s dependence on Chinese suppliers is any indication, the US hasn’t yet figured out how to equip its innovation base the necessary industrial heft.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSBritain’s water crisis

The UK, an island nation surrounded by water, is running dry. Climate change, over-reliance on aquifers, and an old water and sewage network are among the key problems leading to drying rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. That could spell trouble for the country’s agriculture. And it could be an obstacle to the UK’s EV battery ambitions, given the water intensity of those operations.

(Photo by cottonbro studio/Pexels)