THE BIG DEAL

The Fed hits the brakes on demand, but who will fix supply?

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rates three-quarters of a percentage point, its most aggressive hike since 1994. The move – likely to be followed up by another hike of 50 to 75 basis points in July – is intended to respond to soaring inflation figures; to dampen demand and therefore cool off an overheating economy. That cooling off is certainly happening: The S&P has notched its worst week since 2020; the Wall Street Journal reported today that a survey of economists found them putting the probability of recession over the next 12 months at 44 percent.

The issue is that the Fed’s interest rates mechanism – like most of the anti-inflation tools at the behest of the US government – is a demand-side response. And today’s inflation is not being primarily driven by employment and wages. Rather, much of today’s inflation can be attributed to shortages of physical production capacity, including in critical, capital-intensive sectors like energy and semiconductors. And aggressive interest rate hikes risk worsening this physical capacity shortage by discouraging the private sector investments necessary to increase supply.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSThe Yen’s dilemma

The Japanese yen is caught between loose monetary policy at home and tightening US Fed policy abroad. That has pummeled the yen, which is nearing its weakest point since 2002 against the dollar. A cheap yen is a double-edged sword: It could help Japan hit its elusive 2 percent inflation target, and also help boost the country’s exports. A cheap yen could also drive a wave of foreign mergers and acquisitions as bidders hunt for bargains, which in turn could revitalize Japan’s sprawling conglomerates. But a cheap yen also means that imports, including critical inputs, will grow even more expensive – amid soaring global commodities prices – hurting consumption. Regardless, for now, the Bank of Japan is sticking with ultra-low interest rates.

USD/JPY (2022, to date)

Fears of (another) Eurozone debt crisis

The European Central Bank (ECB) faces its own dilemma. Today’s economic challenges are hard enough for a single national economy. They pose a whole other level of challenge for a multilateral bloc with an, er, diversity of economic health statuses. The ECB has confirmed that it will hike rates next month to curb record-high inflation. This might make sense for the zone’s more robust economies. But it will also raise borrowing costs and put pressure on the EU’s most indebted member states like Italy and Spain. And that, in turn, is sparking worries of a eurozone debt crisis. To address those concerns, the ECB held an emergency meeting and announced a new bond-buying plan – dubbed a “new anti-fragmentation instrument” – to narrow borrowing costs across the region. Details are scarce for now, but the move at least provided a short-term confidence boost for the eurozone. The spread between yields on Germany’s and Italy’s benchmark 10-year government bonds, a measure of financial stress in the currency bloc, narrowed following the ECB’s announcement.

A pyrrhic victory for the WTO?

The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act will take effect next week – accelerating the reckoning over international exposure to China’s human rights atrocities. And this reckoning extends well beyond the United States: Germany’s largest trade union IG Metall, representing workers in the industrial sector of Europe’s largest economy, has demanded that Volkswagen withdraw from Xinjiang over human rights abuses against Uyghurs. Volkswagen has so far defended its presence in Xinjiang, with its CEO saying last month that the company’s footprint there “leads to the situation improving for people.” That position looks set to be harder to maintain as pressure piles on the automaker, including the German government’s decision last month to deny the firm investment guarantees for new projects in China.

But the elephant in the room: Xinjiang is an industrial hub for China, which itself is an industrial hub for the world. How much are companies actually able to do – and is there the political will to make them follow through?

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSJoe Biden vs. Big Oil

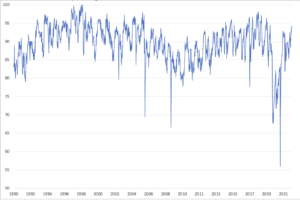

With the average gas price per gallon in the US above five dollars per gallon, the Biden administration is trying to cast oil companies as responsible: The US president sent a letter to oil and gas CEOs on Wednesday pushing them to boost national refinery output – calling their record profit margins “not acceptable” and warning that he is “prepared to use all reasonable and appropriate Federal Government tools and emergency authorities to increase refinery capacity and output in the near term.”

This blame game belies more entrenched structural constraints, and the real shocks that have catalyzed today’s energy crunch. US crude processing has in recent weeks been running at close to maximum capacity, hitting 94 percent this month. The American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers trade association has responded to Biden by arguing that adding incremental refining capacity without corresponding increases in crude oil production fails to address the fundamental supply problem, and risks simply driving up crude oil prices. Meanwhile, there’s a timespan mismatch at play: Re-investment in crude refining now would take years to bring into operation. And, of course, today’s energy shortage is more than anything else a function of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – not oil and gas profit margins.

Weekly US Percent Utilization of Refinery Operable Capacity

Russia’s trump card, and the EU’s gas crunch

On Wednesday, Russia gas monopoly Gazprom announced that it is cutting natural gas supplies to Germany through the Nord Stream 1 Pipeline by 60 percent – a day after announcing an initial 40 percent reduction. Gazprom is citing technical issues, in the form of delays in a turbine repair. The European Union is skeptical. These supply cuts came just as the leaders of France, Italy, and Germany visited Kyiv; Germany’s government has said it suspects that Gazprom is making a political point, and undermining Berlin’s efforts to stock up on gas supplies in advance of winter. Either way, the bottom line is clear: For all of the EU’s strong narrative stances, it still relies on Moscow for energy. And energy matters. As long as that reliance continues, the EU’s hands are more tied than anyone is acknowledging when it comes to pushing back against Russia’s aggression.

China is splurging on semiconductor machinery, whether the US likes it or not

Even as the US has tried to handicap transfer of advanced semiconductor equipment to China – including by placing restrictions on SMIC, a powerhouse State-owned chip manufacturer – Beijing continues to forge ahead with its semiconductor ambitions. Data reported by Bloomberg show that China remains the top global buyer of semiconductor tools and machinery. US chip firms suggest that Chinese companies are snagging this gear by paying above-market prices, outbidding their competition to acquire advanced technology that promises long-term strategic advantage.

This underscores the limitations of US policy: Washington appears not to be doing enough to ensure that its major chipmaking equipment manufacturers aren’t helping China gain technological capabilities. Nor do Washington’s policy tools address the reality of a globalized world, and the portals to technology acquisition it creates. Much of the chip equipment spending in China is by multinationals with production facilities there; US chip equipment firms risk sidestepping US export restrictions by building capacity elsewhere. And, perhaps the biggest problem, Washington hasn’t paired its defensive moves with proactive investment: As long as China’s are the biggest buyers in town, the technology will flow there. Money talks, louder even than multilateral export controls.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSAll eyes on Xinjiang

The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act will take effect next week – accelerating the reckoning over international exposure to China’s human rights atrocities. And this reckoning extends well beyond the United States: Germany’s largest trade union IG Metall, representing workers in the industrial sector of Europe’s largest economy, has demanded that Volkswagen withdraw from Xinjiang over human rights abuses against Uyghurs. Volkswagen has so far defended its presence in Xinjiang, with its CEO saying last month that the company’s footprint there “leads to the situation improving for people.” That position looks set to be harder to maintain as pressure piles on the automaker, including the German government’s decision last month to deny the firm investment guarantees for new projects in China.

But the elephant in the room: Xinjiang is an industrial hub for China, which itself is an industrial hub for the world. How much are companies actually able to do – and is there the political will to make them follow through?

Wall Street salaries vs. common prosperity

For years the world’s premier global banks have eagerly eyed the huge Chinese market as the next frontier for fat profits. They had reason for optimism: Beijing was cracking open its capital markets to foreign competition, allowing more global banks to take full ownership of joint ventures. Yet the turmoil of zero covid lockdowns, unpredictable regulatory crackdowns, and a broad economic slowdown – not to mention the intensifying US-China showdown – have dampened enthusiasm. Now, Beijing officials are going one step farther: They are warning the likes of Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse over excessive banker pay that’s contrary to the Communist Party’s “common prosperity” agenda. This is where things get personal. Could it be a final straw?

(Photo by Pexels)