Economic alarm bells ring in China – and the rest of the world feels the squeeze

The Shanghai lockdown, conducted as part of Beijing’s fervent adherence to Covid Zero, has achieved a zero of another sort: zero car sales in Shanghai for April. That statistic is reflective of a broader set of indicators released this week that paint a worrying picture for the economy: Plummeting retail sales, asset sales, and industrial output, all amid soaring unemployment. And if that picture is unsettling for China, it’s even more troubling for the rest of the international economy – dependent on China for both production and sales, and unlikely to be bailed out by Beijing even if domestic Chinese players are. Apple, for example, has seen production at key suppliers shut down, and is now looking to develop capacity outside of China; Tesla is chafing at a now-stalled Chinese sales market.

Meanwhile, Beijing appears to be holding off on deploying any major economic tools to mitigate the potential crisis – especially vis-à-vis international players. Yes, Friday saw an unexpectedly large cut in the five-year loan prime rate, a key benchmark rate for mortgages, which could offer some relief for the battered housing sector. But officials have kept two other key rates—one-year loans and the medium-term lending facility—unchanged. And thus far, no demand-side stimulus of meaningful scale has been deployed. Instead, Beijing is focused on supply side measures like infrastructure investment that promise to boost GDP figures for the year, but not solve Apple or Tesla’s dilemma.

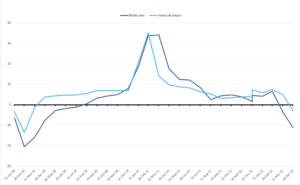

US stocks continue their slide

US stock markets are now on a seven-week losing streak, the longest such streak since the Great Depression. The S&P 500 briefly dipped into bear market territory, defined as a 20 percent decline from its peak, on Thursday before closing the week just shy of that threshold. The reasons for the fall are relatively clear: Inflation – driven by stimulus-fueled demand, supply chain snarls, shortages of all kinds, and a lack of domestic economic resilience – the chaos that the Russia-Ukraine war has unleashed on energy and commodity markets by the Russia-Ukraine war; fear that the Fed’s actions to tame inflation will result in a hard landing and a recession; and, of course, China, where lockdowns have compounded supply chain headaches and muted global demand. All of which boil down to the lack of real economy undergirding the US market.

The EU asks, again, if it can be a buyers’ cartel

Russian oil and gas revenues have soared, a perverse consequence of Europe’s dependence on the country’s fossil fuels even as Moscow continues its brutal war of aggression against Ukraine. Moscow’s coffers are reaping the rewards of its military’s war crimes, while the ruble continues to strengthen. Now, the EU is weighing stopgap measures – short of bloc-wide embargo. One of the leading candidates: A price cap on Russian oil and gas. A EU-enforced price cap would essentially position the bloc as a buyers’ cartel, in theory forcing Russia to accept a lower price or sell almost nothing at all. There are important details to work out, including the reality that there would be every incentive for member states to defect. And, of course, the question of whether Moscow would respond to a price cap by simply turning off the taps. Plus, don’t forget how little has come out of the EU’s March 31 announcement that the bloc would act as a gas buying cartel.

Regardless, the crucial longer-term lesson here, as officials debate how to punish Russia without unduly hurting their own economies, is that energy dependence on a geopolitical competitor has consequences. And that’s a lesson that has to be internalized across the western world, before it’s too late – and especially when it comes to emerging industries like those of the energy transition.

The EV industry leans into integration…

Battery prices are rising, squeezed upward by soaring costs of raw materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. And prices are set to remain high: Demand for critical minerals is expected to continue to outstrip supply. EV makers scrambling to control costs and protect margins may need to adjust their business models. Doing so will mean investing in vertically integrated value chains, or some equivalent thereof. Options include:

- Directly entering the upstream mining segment, through either direct or partial ownership of mining projects, as has been prominently suggested by Tesla’s Elon Musk.

- Directly entering battery making. Over 80 percent of North American battery gigafactories in the pipeline are now wholly or jointly owned by automakers, up from 20 percent in 2019.

- Partnering with other automakers to achieve greater economies of scale: Already, Ford and Volkswagen have expanded their partnership to a second EV model, while General Motors and Honda will work together on affordable EV models. And this week, Volkswagen said it was exploring a partnership with India’s Mahindra for EV components.

All of these augur an era of renewed emphasis on scale and integration. That in turn raises the question of whether business model upheaval in the auto industry is likely to spill over into other sectors.

…Even as automakers face a new competitive threat

Taiwan-based Foxconn, the iPhone assembler and the world’s largest contract manufacturer, this week closed a deal with US EV company Lordstown Motors to buy the start-up’s Ohio plant. While Foxconn has already made its EV ambitions clear, its purchase of the Lordstown plant now earns it a solid foothold in the US EV market. It also removes yet another key manufacturing node from a US company. This data point undermines the narrative of renewed investment in US production by US companies. It also raises the question of whether the EV revolution is going to create a new front in the auto manufacturing competition, with traditional automakers squeezed by companies like Foxconn that specialize in advanced manufacturing and components for other sectors.

The London Metal Exchange wants to rebuild its reputation

Back in March, the London Metal Exchange – owned by Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing – cancelled billions of dollars of trades in a bid to resolve a chaotic nickel short squeeze. This has undermined traders’ and investors’ trust in the exchange’s ability to serve as a neutral arbiter. The LME now wants to make amends. The proposal: Increase transparency and step up market surveillance powers, including by requiring members to report all over-the-counter positions on a weekly basis. If this regulatory change is approved, it could have broad impacts on global commodity markets beyond the metals sector. It also raises the question of whether this is indeed a move toward greater neutrality – or a veiled attempt to gather superior information on the commodity market.

(Photo by Pexels)