Can China rejig its economic model to tap new growth—and does it need double-digit GDP expansion to wage asymmetrical industrial competition? Meanwhile, watch out for shifts in global LNG flows and trading, the rise of Vietnam as a rare earths magnet hub, and Germany’s bid to tighten foreign investment controls. Plus: what de-dollarization?

SLOW DOWN FOR WHAT?

China’s growth engine is stalling

There are a couple points of clarity amid all the uncertainty around the Chinese economy.

First, multiple confounding factors are dragging down growth: mounting debt, weakening demand, diminishing returns on its investment-driven model, a shrinking population, and increasingly unpredictable authoritarian rule—in turn reinforcing the West’s desire to derisk and decouple from China, adding to the latter’s pile of geoeconomics challenges.

Second, the China’s economy is unlikely to collapse anytime soon.

Less clear is whether and how Beijing will manage to dig itself out of this rut.

The Chinese economist Keyu Jin (daughter of former Chinese deputy finance minister Jin Liqun) argues that “the recent growth slowdown is more a symptom of a reform stalemate than it is of diminished potential.” Similarly, Peking University’s Lin Yifu reckons “new structural economics”—changing the structure of demand to promote structural changes—can tap new growth.

Perhaps. China could certainly do with reforms and restructuring, like increasing the household share of GDP or reining in the state’s ability to demolish whole industries at will. Whether Beijing can stomach the necessary political and economic tradeoffs is another question.

Something else to keep in mind: even a stagnating China can apply its state-directed, enterprise-driven, and asymmetrical approach to industrial competition. Beijing doesn’t need double-digit GDP growth to flex control of upstream nodes as leverage against rivals.

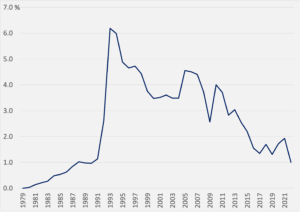

Foreign investment inflows to China, share of GDP

Source: World Bank

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSVietnam’s rise as a rare earth magnet hub

South Korean and Chinese rare earth magnet markers are opening factories in Vietnam to diversify supply chains away from China, Reuters reports. Vietnam’s untapped rare earth deposits are a draw, but China still controls the bulk of global processing and magnet making capacity.

So even if, when its Vietnam plant reaches full capacity, South Korea’s Star Group International is set to produce nearly 3% of the 2022 global neodymium magnet output—equivalent to nearly half of US imports of the magnets last year—the reality of China’s full-supply-chain rare earths dominance endures.

Nickel slump and bump

Major miners are struggling with what should be a lucrative business in the battery metal nickel. BHP reported a slump of over 60% from a year earlier in earnings, while Glencore posted a first-half loss, in their respective nickel businesses.

The cause of their woes: a flood of new battery-grade nickel supplies from Indonesia, thanks to a technological breakthrough spearheaded by Chinese companies, which has dragged down prices. In recent weeks, however, nickel prices have surged as Indonesian authorities launch a probe into illegal mining of the metal.

But that’s unlikely to keep downward price pressures at bay for long as Indonesia continues to expand production of high-quality nickel. Just this week, China’s nickel producer Tsingshan started commercial production of refined nickel in Indonesia.

Shifting LNG flows

German chemical giant BASF has signed a long-term contract to buy American LNG from the Texas-headquartered Cheniere, as German companies continue to source new supplies to replace Russian gas.

Elsewhere, China is emerging as a global LNG trader. Both private and state-run importers are opening or expanding trading desks in London and Singapore to manage market swings. That will give China greater global LNG pricing power—a stated national goal.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSFrom BRICS to…BRICSSEEAU?

BRICS welcomed six new members (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina and the United Arab Emirates) into its ranks as the bloc of developing countries seeks to increase their geopolitical clout on the global stage and serve as a counterweight to the West-dominated G7.

Skeptics might note that the bloc’s increased size doesn’t automatically translate into coherent influence. That’s especially so given that two of the new members are the largest IMF debtors (Argentina and Egypt); four of them have inflation rates ranking in the global top 20 (Argentina, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia); one is struggling with deflation (China); and two are sworn enemies (Saudi Arabia and Iran).

Germany eyes tighter foreign investment controls

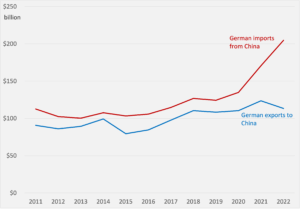

German economic minister Robert Habeck wants more stringent regulations to scrutinize foreign investments in Germany, Handelsblatt and Reuters report. One significant expansion of government auditing powers would be to examine investments in which an investor gains access to a Germany firm’s products or technologies through licensing agreements, not merely voting shares. But even as Germany beefs up its China strategy, its carmakers are casting their lot with China.

Germany’s trade with China, 2011-2022

Source: UN Comrade

BYD spots an IRA backdoor

Chinese auto giant BYD—the world’s largest seller of EVs and hybrids, and a leading battery maker—is in talks with South Korean car maker KG Mobility Corp. to build a joint battery plant in South Korea.

For KG Mobility, the tie-up offers the possibility of accessing low-cost battery packs for its line of SUVs. And for BYD, batteries produced in South Korea could potentially benefit from the US’s IRA tax credits. As Tu Le of Sino Auto Insights puts it: “Is this an attempt to enter the US through a backdoor? You better believe it!”

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSDurable dollar dominance

De-dollarization, if it were to happen, would be a disruptive phenomenon. So far, there’s little sign it’s happening. The latest data global financial messaging service Swift shows the use of the dollar in global payments rose to a record high of 46% in July, up from about 33% a decade ago. Meanwhile, the euro’s share fell to a record low at just under a quarter, while the yuan’s share rose to over 3% for the first time.

(Photo by Edward Eyer/Pexels)