The EU goes head to head with the US on industrial policy, right when cooperation is most necessary. Plus, BP says that fossil fuels are out but US oil production surges and the world can’t kick coal, China’s pending export restrictions on solar and rare earth technology, and General Motors pushes ahead with investments in vertical integration. Plus: disinflation with a side of hot jobs, Made in China Covid antivirals, and, of course, China’s spy balloon.

THE INDUSTRIAL POLICY THROWDOWN

Europe’s Green Deal vs. America’s IRA

The EU this week unveiled its “Green Deal Industrial Plan.” It’s a counteroffer to the United States’s massive Inflation Reduction Act, and aims to correct what the bloc describes as “subsidies abroad [that] are uplevelling the playing field.” The plan proposes to increase levels of state aid to allow more targeted subsidies for renewable energy industries, to repurpose existing funds, to speed up permitting for clean tech projects, and to set up a new fund to support emerging technologies.

Will it work? A major challenge is that, to state the obvious, where the US is a single country, the EU is many: Relaxing state aid rules could pit bigger economies against smaller ones. That in turn could fragment the internal market—the core of the EU’s economic model.

Then there are the ideological concerns: The Financial Times argued this week against the “orgy of subsidies” thrown at the battery industry by the IRA (and now the EU’s Green Deal). Batteries are about “[s]cale, capital, and cost: it all points to China,” the essay notes. It urges the West to focus instead on high margin areas of the EV industry, like software, data, and design.

But the FT’s case against what it calls the “great battery industry fallacy,” misses a broader point: It’s the West’s singular focus on high value-add downstream segments of value chains, while neglecting and outsourcing the upstream and midstream, that has hollowed out its industrial base and led to an overwhelming reliance on China. The IRA and Green Deal are an attempt to correct that asymmetry. Forgoing domestic battery manufacturing capacities to chase higher downstream margins would do nothing to shore up economic security.

Still, our lingering questions: How to reconcile this subsidy tit for tat with today’s unprecedented imperative of US-EU cooperation? And is this subsidy war an ill-fated effort to replicate Chinese approaches to industrial policy at the expense of free(r) market solutions that could better leverage enduring US and EU strengths?

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSRecord US oil production

BP’s latest annual energy outlook projects that fossil fuel’s share of primary energy will fall from 80% in 2019 to between 20–55% by 2050. Meanwhile, renewables’ share will rise from 10% to between 35- 65% over the same period. More specifically, oil and gas demand are projected to be 5% and 6% lower, respectively, by 2035 than BP has previously modeled.

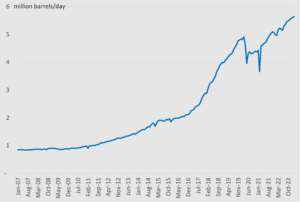

But while oil demand may be on a long-term downward trend, production in the Permian Basin is surging, finally. That is forecast to drive overall oil production in the US to a new high of 12.4 million barrels per day this year and 12.8 million in 2024, beating 2019’s record of 12.3 million barrels per day, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The production bump is likely a welcome relief for the US government, which has for months tried to incentivize more domestic production, in part through a buyback plan using fixed-price forward contracts to replenish the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Oil Production, Permian Basin

Source: US Energy Information Administration

Can’t quite kick coal

When it comes to coal, for all the narrative of aggressive phase out, a who’s who of the world’s most influential energy consumers simply cannot afford to do so just yet.

Take India. Its government, which has no formal timeline for phasing out coal, has asked utilities to not retire coal-fired power plants until 2030 so as to meet surging energy demand driven. Far from minimizing coal use, India will reportedly use an emergency law to compel power plants running on imported coal to operate at full capacity.

China, too, is not yet ready to ramp down coal. The country will speed up the construction of coal- and natural gas-fired plants this year (though renewable energy capacity is projected to grow even more quickly). Some of those power plants may even burn Australian thermal coal, as imports resume following the lifting of an unofficial embargo on the commodity imposed in 2020.

Over in Europe, use of coal-fueled power rose last year—but not as much as feared, thanks in part to an increase in renewable energy production to generate a record 22% of electricity in the EU in 2022.

And in Japan—the world’s third largest coal importer—power utilities are diversifying import sources and switching to lower quality grades in a bid to reduce thermal coal import costs and replace Russian coal.

China’s solar and rare earth export restrictions

While the West scrambles to build supply chains for the energy transition, China is considering moves that could stymie those efforts. A draft of Beijing’s list of technologies subject to export bans and restrictions issued at the end of January includes products and processes key to the energy transition: Advanced technology used to make solar ingots and wafers, and a range of rare earth products and processes.

The potential solar technology restrictions have been widely discussed. Once approved, Chinese solar manufacturers would have to obtain a license to export the listed technologies. Less discussed, but more expansive, are pending export restrictions on rare earth products and technologies. These include a full ban on rare earth extraction and processing technology and technology for producing key rare earth magnets, as well as restrictions on technology for producing aluminum-lithium alloys containing rare earths.

Will these restrictions have bite? On rare earths, there are already numerous companies outside of China that have the know-how to make rare earth magnets; their pressing challenges are scaling up operations and diversifying and securing inputs. As for solar, know-how exists outside of China, too. But there’s a greater risk in the overwhelming reliance on China for upstream inputs, including polysilicon.

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSThe manufacturing recession everyone’s missing

“The disinflationary process has started,” US Fed chair Jeremy Powell said this week. But it’s also “really at an early stage.” That means the central bank isn’t ready to declare victory and stop rate hikes. In fact, “a couple more” rate hikes are in store this year, in addition to Wednesday’s quarter-point raise. Markets nevertheless lapped up Powell’s relatively dovish tone, spurring a rally that sent the S&P 500 and Nasdaq up 1% and 2% respectively on Wednesday.

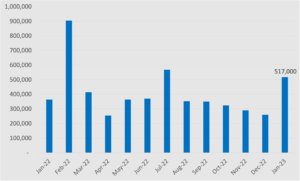

But while there are multiple signs of inflationary pressures easing—including decelerations in prices, employment costs, and consumer spending—Friday’s red hot jobs report, with 517,000 jobs added in January and unemployment hitting a five-plus-decade low of 3.4%, underlined the Fed’s continuing struggle to cool prices.

The mainstream narrative is that these are signs of a still-robust economy, even as the Fed wrestles with inflation. But here’s what the conversation risks missing: US manufacturing has contracted further, to sit squarely in recession territory. The Institute of Supply Management’s manufacturing PMI for January dropped to 47.4 from 48.4 in December—the third straight monthly contraction and the lowest level since May 2020.

US monthly change in jobs, 2022-2023

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Mixed economic signals from Europe

It’s a mixed bag over in Europe. Germany’s economy unexpectedly shrank by 0.2% in Q4 over the previous quarter, the first GDP contraction since Q1 2021. Dragging on the economy was a decline in consumer spending, hampered by soaring inflation driven by high energy prices.

But Europe overall fared alright: The eurozone economy grew 0.1% in Q4, compared with 0.3% in Q3. While that’s barely above the recession threshold, the eurozone economy overall ended up performing better than that of the US and China last year: It grew 3.5% in 2022, versus 3% for China and 2.1% for the US.

In the UK, economic gloom and frustrations prevail. Wednesday alone saw half a million workers across numerous sectors striking to demand higher pay amid surging costs of living. More strikes are expected next week, including among healthcare workers.

GM splurges on lithium and secures rare earth magnets

General Motors is charging ahead with its vertical integration efforts. This week alone brought two key developments in its endeavor to build a full EV supply chain.

First, GM announced a $650 million investment in Lithium Americas in a deal that will see the companies jointly develop the Thacker Pass mine in Nevada, and will give GM exclusive access to the first phase of production there. GM says it’s the largest ever investment by an automaker to produce battery raw materials; the project is expected to produce enough lithium carbonate for batteries to power up to 1 million EVs per year. GM currently has three battery factories in the US developed jointly with LG Energy Solution, though a planned fourth one was recently scrapped, in part due to the uncertain macroeconomic outlook.

GM is making moves on rare earth magnets, too. It just inked a binding agreement this week with Germany’s Vacuumschelze for a long-term supply of permanent magnets. As part of the arrangement, Vacuumschelze will build a magnet facility in North America. It’s set to come online in 2025 and use “locally sourced raw materials,” per Reuters.

In other battery minerals news: The Philippines is following in Indonesia’s footsteps and considering a tax on nickel exports as a way of incentivizing more value-added processing capacity at home.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORSMade in China Covid antivirals

Last weekend (January 28-29), Chinese drug regulators approved two new oral covid antiviral pills for sale: Junshi Biosciences’ VV116, and Simcere Pharmaceutical Group’s Xiannuoxin. Alongside azvudine, approved in China last summer, the country now has three approved homegrown Covid antiviral pills, in addition to Pfizer’s Paxlovid and Merck’s molnupiravir.

As we’ve previously noted, the case of VV116 is particularly interesting: it’s based closely on an antiviral invented and patented by US pharma giant Gilead. Early on in the pandemic, however, Gilead chose not to prioritize that antiviral, GS-441524, instead focusing on developing its intravenous antiviral treatment, remdesivir.

While Gilead dithered on GS-441524, scientists from Junshi and the Chinese Academy of Sciences managed to tweak it to get around Gilead’s patent, develop VV116, and bring it to market in China. Phase 3 clinical trial results published in December in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that VV116 is non-inferior to Paxlovid as a Covid treatment.

And, of course, the spy balloon

You thought we could avoid commenting on the Chinese spy balloon? Of course not. On Thursday, media reports surfaced that a Chinese intelligence gathering balloon had been spotted floating over the United States. Over the hours and days that followed, it came out that this was not the first such incident, Secretary of State Blinken cancelled his upcoming trip to China, and the State Department declared the balloon a “violation of sovereignty.” And then, on Saturday afternoon, as the balloon moved off the coast of the United States, two F-22 fighter jets from Langley Air Force Base downed it with a single missile, about six miles off the South Carolina coast. Beijing called this an “excessive reaction.”

Washington is promising that the balloon posed no real threat. That’s entirely believable. The real story here is that public pressure turned an event that the Biden administration appeared intent on tamping down into a rapidly escalating diplomatic stand-off. The Pentagon had been monitoring the balloon for days when civilians in Montana spotted it, and media attention jumped in, on Thursday. Even after the balloon became a dinner table conversation, the administration appeared intent on letting it float on. The decision to shoot it down on Saturday seems to have stemmed in large part from public attention (and pushback at the laissez faire attitude), as well as pressure from the GOP.

The big question: Does this mean that public appetite for a strong stance vice China exceeds that of a Washington that’s all about “managing competition?” And, if so, what does that portend, both for pressures on this administration and those that will define the next one?

(Photo by Sergio Souza, Jonathan Peterssen/Pexels)