THE BIG BILL

The CHIPS Act is law, but does it matter?

The big industrial policy story of the week: On Tuesday, President Biden signed the Chips and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS Act) into law. The 280 billion USD legislation is intended to strengthen US semiconductor manufacturing, research and development, and supply chain security – for the sake of domestic US industry, of course, but also competition with China. The law features over 52.7 billion USD for semiconductor manufacturing, including 2 billion for so-called legacy chips that are essential to the auto and defense industries; a 25 percent tax credit for domestic investment in semiconductor projects; and 200 billion USD for chip-related research.

In other words, the CHIPS Act constitutes a lot of dollars going to a strategic domestic industry. It is a signal that Washington is getting serious about today’s production-based international competition. But the CHIPS Act is also wildly inadequate for this competition. First, the legislation skews toward semiconductor R&D, leaving core, more upstream nodes of the semiconductor value chain (read: packaging and testing, material inputs, and the markets into which semiconductors are sold) largely unaddressed; it focuses on expertise not the ability to make. Second, the CHIPS Act fails to address the reality that much of this R&D risks flowing to China – thanks in large part to Beijing’s capture of leading international semiconductor companies.

Finally, and the biggest issue: Semiconductors, while of course important, are only one slice of the industrial competition underway. If it takes the US two years, bipartisan consensus, and a near-perfect alignment of the stars to address every other slice, nothing will happen. That leaves one huge question moving forward: Is the private sector ready to take the initiative? Will the US private sector treat the CHIPS Act as a signal from Washington to start rethinking economic logics and proactively investing in domestic production, in semiconductors and beyond – on the assumption that regulatory and geopolitical dynamics will support the bet? Or will they keep waiting on Congress to dole out cash before making moves?

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORS

FACTORSGas prices are down, but the fuel scramble continues

Global oil prices are edging lower; US retail pump prices fell below 4 dollars per gallon this week. But there is more to the energy picture than oil and gas. LNG and coal prices are still climbing, thanks in no small part to upward pressure from Asian demand. South Korea and Japan are rushing to buy extra cargoes of LNG to boost storage and avoid winter shortages, especially after summer heatwaves and amid ongoing uncertainties about the Russia-Ukraine war. These moves to secure supplies outside of existing long-term contracts require outbidding European buyers, further squeezing the already-tight global LNG spot market – and exacerbating international shortage. And if Asia is squeezing LNG prices, Europe is doing the same for coal. The EU’s ban on Russian coal came into effect this week. Now, member states have to find supplies elsewhere, including Australia and Indonesia. This is putting new pressure on the global market and lifting the Asian coal futures curve substantially.

Plus, there are wildcards in this week’s energy picture. Japan has announced that it intends to keep its 30 percent stake in the Sakhalin-1 oil and gas project in Russia, because it is an important source of fuel imports (and everyone these days needs fuel). Not that Tokyo has much choice in the matter: Russia this week banned investors from “unfriendly” nations from selling shares in key energy projects, including the Sakhalin-1.

Turkey plays metals middleman

Turkey is playing a key intermediary role in facilitating sales of metals to Russia, according to the head of the Istanbul Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metals Exporters’ Association. With Russian access to metals from the West restricted due to sanctions, Russian buyers are turning to Turkey to serve as its “bridge and warehouse.” Similarly, EU companies are turning to Turkey as a conduit to sell their metals to Russia, according to the industry group. Data bears this out: Turkey’s metal exports to Russia rose by 26 percent year-on-year by August 8. This is just the latest example of the leaks in the West’s sanctions war on Moscow – and how readily the international private sector finds workarounds to it. It

Tesla locks in more nickel – but China got there first

Tesla has signed deals worth 5 billion USD to secure nickel materials from Indonesia for its lithium batteries, according to an Indonesian government official. The carmaker hasn’t confirmed the news publicly, but it would be in line with the company’s globe-spanning effort over the past year to secure deals with nickel suppliers. As for the latest contracts with Indonesia, the official said that Tesla has begun buying “two excellent products” produced by nickel processing companies operating in the country’s Morowali Industrial Park. What was less emphasized in the interview: The facility is a joint-venture that’s two-thirds owned (p.12) by Chinese metals giant Tsingshan.

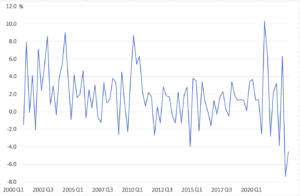

A US productivity slump

US workers’ output-per-hour is tumbling. It fell 4.6 percent in the second quarter at an annualized rate and 2.5 percent over the last year – the biggest drop ever recorded. That’s a worrying development. Falling productivity pushes up labor costs. In today’s inflationary moment, that’s not exactly awesome. Nor is it a great sign for growth or development in the US economy.

What gives? Some are arguing that disruptions to industries are forcing workers to reconfigure their jobs, and that it takes time to settle into a new rhythm; others suggest that red hot job growth demands expending labor resources training new workers and bringing on less qualified, and therefore productive, workers. Our question: Could these be the rippling consequences of a remote work disruption?

Nonfarm business labor productivity, quarter-on-quarter percentage change

US Department of Labor

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETS

MARKETSChina flexes its delisting muscles

Five Chinese state-owned giants – energy majors PetroChina, Sinopec, and Shanghai Petrochemical; China Life Insurance, and the Aluminium Corp. of China – all announced that they will voluntarily delist their American depository shares from the New York Stock Exchange. The coordinated move seems to reflect a two-stage negotiating game on the part of the Chinese government, intended to increase both its leverage over its domestic players and that over Washington.

Some direct possible interpretations, none of which are mutually exclusive: First, that Beijing sees limited possibility for a deal with Washington regulators to avoid a mass delisting of Chinese firms. Second, that Beijing thinks a workaround is possible: Delist a subset of companies that have sensitive data, while allowing other US-listed Chinese firms to comply with US Securities and Exchange Commission rules. And third, that this is Beijing flexing its coercive muscle vice Washington regulators – and its companies – to land the deal and control it wants.

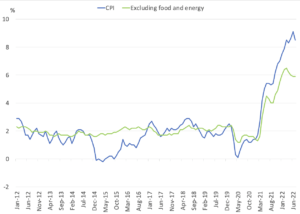

US inflation takes a (small) breather

US inflation figures are in for the month of July: Price are up 8.5 percent year over year, below expectations and lower than last month’s figure of 9.1 percent. This comes thanks in large part to a steep drop in energy prices – namely gasoline, which fell 7.7 percent last month. Meanwhile, the latest core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, is up 5.9 percent for the year, matching the previous month’s reading.

This is unquestionably a sign of relief. Stock markets cheered the news, expecting that the Fed will pull back on its rate hiking moves in response. But keep in mind that for all the incentives to declare victory, inflationary pressures remain strong. For example, food prices continue to soar: The food index saw a 12-month increase to 10.9 percent, the fastest growth since 1979; eggs are up 38 percent year over year and coffee 20 percent. And the Fed will likely continue raising rates until it sees strong evidence that inflation is falling.

Year-on-year change, monthly, of US Consumer Price Index

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

…while China’s inflation numbers spell a different kind of trouble

Meanwhile, China’s CPI jumped 2.7 percent in July from a year earlier, the highest level in two years. The increase was driven by surging pork prices, which rose 20.2 percent last month. Strip away volatile food and energy prices, though, and you get a different story. China’s core CPI only rose 0.8 percent in July, down from 1 percent in June and hitting the lowest level in 14 months. That points to weak domestic demand, weighed down by lackluster consumer confidence, a real estate downturn, and stringent COVID-19 lockdowns. Should these trends continue, they could add up to create largescale deflationary trends. And Beijing is not indicating any monetary stimulus on the horizon; officials have hinted that broad-based cuts are unlikely and that the priority is to maintain liquidity at “reasonable” levels.

The IRA to automakers: work for your EV tax credits

The Inflation Reduction Act is moving along: It passed the Senate 51-50 last Sunday (Aug. 7), cleared the House on Friday, and now heads to President Joe Biden’s desk. A major component of the 740 billion USD bill is 370 billion for climate change, including tax incentives to spur EV demand. But those come with a critical condition: Sourcing rules put in place by Senator Joe Manchin require that for an EV to receive the tax credit, at least 40 percent of critical minerals used in its battery must be sourced from the US or a free trade partner by 2024. That threshold will ramp up to 80 percent by 2027. Carmakers are throwing a tantrum. But this condition could contribute precisely the carrot-stick combination US industry needs: At least in the short run, most US EVs do not meet the requirement. Here therefore is the push that carmakers need get cracking on minerals extraction and processing investments.

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS

DISRUPTORS(17 + 1) – 3 = ?

And then there were 14. Latvia and Estonia this week quit China’s trade-focused clique of 17 Central and Eastern European countries, following Lithuania’s departure last year. This is another sign that Beijing’s efforts aggressively to pursue economic ties with Europe are losing momentum – in large part a function of close China-Russia ties, Chinese strong-arming, and, a product of both, growing tension between Beijing and Brussels. Beijing will undoubtedly now redouble efforts to solidify relations with and influence over other allies, both those remaining in 14+1 and elsewhere in the international system. Note for example Beijing’s ambitions to transform the Pacific island chain, including through sweeping agreements with Pacific island nations to expand Beijing’s presence in security and regulatory affairs.

The bigger question: What comes next for Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania? It’s one thing to reject China; another thing to find an alternative. The crucial follow-up for these countries and, especially, the major incumbent international leaders is to build strategic multilateral alliances.

(Photo by Pexels)